Friedrich Wieck (1785-1873) is best-known as Clara Wieck Schumann’s litigious father, the man who did everything he could to keep his daughter from marrying Robert Schumann.

Clara Wieck at 16 years old

However, he was also a well-respected piano teacher. Despite the fact that he only took six hours’ worth of piano lessons over the entire course of his life, he single-handedly developed a method to train one of the greatest pianists of the nineteenth century.

Today, we’re looking at that method and how Friedrich Wieck trained Clara Wieck Schumann.

The Beginning Basics of the Wieck Method

Here’s how Wieck believed that piano training should start.

First, lessons should happen three times a week.

Begin by teaching students the musical alphabet. Explain to them how, in musical notation, the alphabet goes “C, D, E, F, G, A, B” and then repeats itself, beginning again with “C.”

Explain and demonstrate how keys going to the right get sharper and higher-pitched, and keys going to the left get flatter and lower-pitched.

Train students to hear the differences in pitch, and what higher and lower pitches sound like next to each other.

From the beginning, start teaching the visual relationships between the black keys and the white keys. For example, every time you see two black keys together, understand that the white key in the middle of that cluster will always be a D; every time you see a cluster of three black keys together, the white key to the right of that will always be a B; etc.

Introducing Rhythm

Friedrich Wieck

Introduce rhythm by asking the student if they can count 1, 2, 3 out loud at a steady pace.

Start repeating 1, 2, 3, and play a piano key or chord simultaneously as the child counts.

In his book, Wieck explained how this process works:

I count 1 of the chords with her, and leave her to count 2 and 3 by herself; or else I count with her at 2, and let her count 1 and 3 alone; but I am careful to strike the chord promptly and with precision.

Afterwards, I strike the chord in eighth-notes, and let her count 1, 2, 3; in short, I give the chord in various ways, in order to teach her steadiness in counting, and to confine her attention.

In the same way, I teach her to count 1, 2, 1, 2; or 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6; at the same time telling her that music is sometimes counted in triple time, and sometimes in 2/4 or 4/4 time.

Clara Wieck Schumann’s Op. 1, published in 1831 when she was twelve

Introducing Chords

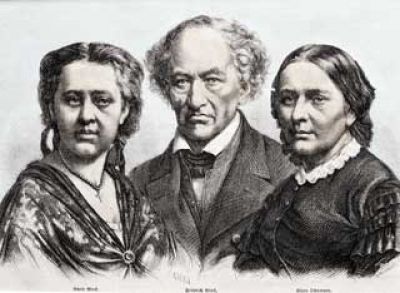

Marie Wieck and Clara Schumann with Friedrich Wieck, c.1880

Next, teach the student the concept of chords.

Wieck wrote about how to hear the difference between major and minor chords:

When several tones are struck at the same time, if they sound well together, they make what we call a chord.

But there are both major and minor chords: the major chord sounds joyous, gay; the minor, sad, dull, as you would say; the former laughs, the latter weeps.

He encouraged teachers not to let students overthink the character of chords, relying on students’ gut instinct of what sounds happy or sad.

Wieck then recommended explaining how the difference in these chords comes from “the third, counted upwards from the lower note C, and depends upon whether you take it half a tone higher or lower, E or E flat.”

This builds on the previously gained knowledge of pitch differences and note names.

How to Talk About More Advanced Techniques

Wieck recommended regularly alluding to more advanced techniques yet to be introduced, telling students things like, “I shall explain this better to you by and by, when you come to learn about the tonic, the third, the fifth or dominant, the octave, and so on.”

He writes:

It is advantageous and psychologically correct to touch occasionally, in passing, upon points which will be more thoroughly taught later. It excites the interest of the pupil. Thus, the customary technical terms are sometimes made use of beforehand, and a needful, cursory explanation given of them.

Clara Wieck Schumann’s Op. 3, published in 1833 when she was fourteen

Finger Dexterity

Clara Wieck at 15 years old

Wieck encouraged teachers to work with pupils at a table to work on finger dexterity and evenness of movement.

You will learn to move your fingers lightly and loosely, and quite independently of the arm, though at first they will be weak; and you will learn to raise them and let them fall properly.

Besides that, we will contrive a few exercises to teach you to make the wrist loose, for that must be learned in the beginning in order to acquire a fine touch on the piano; that is, to make the tones sound as beautiful as possible.

A Focus on Theory

Wieck believed that teachers should delve into more advanced theory immediately.

He specifically emphasised teaching the whole-step/half-step patterns of a major scale, starting with C major to demonstrate. He recommended that teachers teach how there are only half-steps between E and F, and then B and C.

In his words:

This is quite important for my method, for in this way the different keys can be clearly explained.

Clara Wieck Schumann’s Op. 4, published in 1835 when she was sixteen

Reading Sheet Music

So when did Wieck introduce reading sheet music? He believed in teaching this later than you might think:

I may perhaps teach the treble notes after the first six months or after sixty or eighty lessons, but I teach them in my own peculiar way, so that the pupil’s mind may be kept constantly active. With my own daughters, I did not teach the treble notes till the end of the first year’s instruction, the bass notes several months later.

He immediately anticipated a reader’s question: so what should a teacher focus on teaching a student before introducing reading sheet music? Wieck’s answer:

- A light touch

- Playing chords from the wrist

- Scales in all keys, performed evenly (separate hands first)

- Cultivating a sense of rhythm

- Dividing bars

- Understanding the relationships between the dominant and subdominant, as well as transposing

Introducing Piano Pieces

Friedrich Wieck

After all of this, Wieck finally began introducing pieces of his own composition:

I teach them to play fifty or sixty little pieces, which I have written…

They are short, rhythmically balanced, agreeable, and striking to the ear, and aim to develop gradually an increased mechanical skill.

I require them to be learned by heart, and often to be transposed into other keys; in which way the memory, which is indispensable for piano playing, is unconsciously greatly increased.

They must be learned perfectly and played well, often, according to the capacity of the pupil, even finely; in strict time (counting aloud is seldom necessary) and without stumbling or hesitating; first slowly, then fast, faster, slow again, staccato, legato, piano, forte, crescendo, diminuendo, &c.

This mode of instruction I find always successful; but I do not put the cart before the horse, and, without previous technical instruction, begin my piano lessons with the extremely difficult acquirement of the treble and bass notes.

His daughter Marie published these studies after his death. You can access those for free here.

Keep Students Interested!

Despite his reputation as a tyrant, Wieck believed that it was important to engage and entertain the student. In this regard, he actually sounds very modern.

I never try to teach too much or too little, and in teaching each thing, I try to prepare and lay the foundation for other things to be afterwards learned.

I consider it very important not to try to cram the child’s memory with the teacher’s wisdom (as is often done in a crude and harsh way); but I endeavor to excite the pupil’s mind, to interest it, and to let it develop itself, and not to degrade it to a mere machine.

I do not require the practice of a vague, dreary, time and mind killing piano-jingling, in which way, as I see, your little Susie was obliged to learn; but I observe a musical method, and in doing this always keep strictly in view the individuality and gradual development of the pupil…

I keep constantly in view the formation of a good technique; but I do not make piano-playing distasteful to the pupil by urging her to a useless and senseless mechanical “practising.”…

But all this must be done without haste, and without tiring the pupil too much with one thing, or wearing out the interest, which is all-important.

Obviously, Friedrich Wieck’s method is very different from most beginning piano methods used today. But maybe modern teachers can be inspired by elements of his unconventional techniques!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter