Pianist Amy Fay was born in Louisiana in 1844. She began studying piano as a child and quickly proved to be very talented.

She studied at the New England Conservatory of Music in the 1860s and, in 1869, took the daring transoceanic journey to further her studies in Germany.

While in Europe, she studied with Liszt’s student Carl Tausig, as well as Liszt himself.

Her letters to her sister served as the foundation for her book Music Study in Germany, which was published in 1880, and offers a tantalising glimpse into what it was like to be around Liszt in the 1870s.

Today, we’re looking at some of the best stories from Fay’s book.

Amy Fay

Liszt could flirt and watch a play simultaneously.

Last night I arrived in Weimar, and this evening I have been to the theatre, which is very cheap here, and the first person I saw, sitting in a box opposite, was Liszt, from whom, as you know, I am bent on getting lessons, though it will be a difficult thing I fear, as I am told that Weimar is overcrowded with people who are on the same errand.

I recognised Liszt from his portrait, and it entertained and interested me very much to observe him.

He was making himself agreeable to three ladies, one of whom was very pretty.

He sat with his back to the stage, not paying the least attention, apparently, to the play, for he kept talking all the while himself, and yet no point of it escaped him, as I could tell by his expression and gestures.

Khatia Buniatishvili Plays Liebestraum No. 3 from Franz Liszt

Liszt was “the most striking-looking man imaginable.”

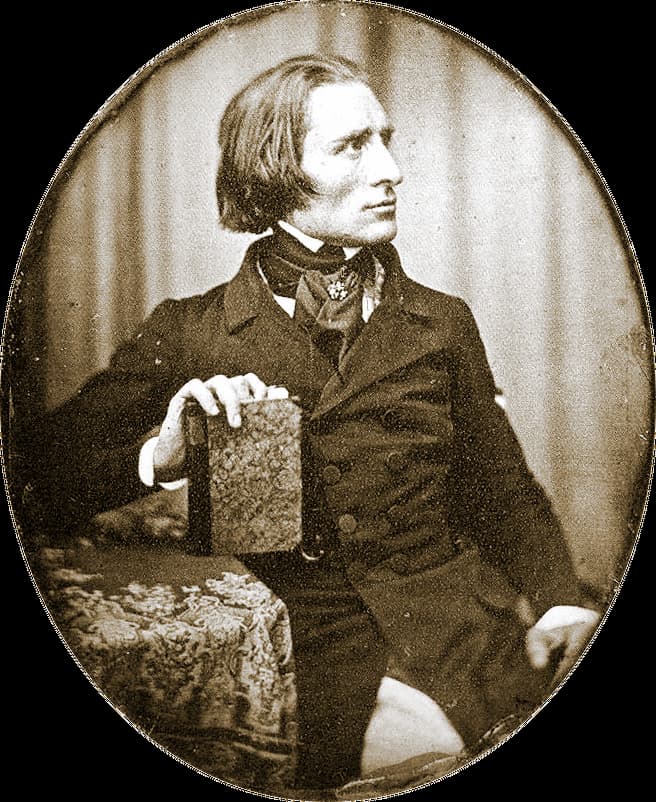

Hermann Biow: Franz Liszt, 1943

Liszt is the most interesting and striking-looking man imaginable.

Tall and slight, with deep-set eyes, shaggy eyebrows, and long iron-grey hair, which he wears parted in the middle.

His mouth turns up at the corners, which gives him a most crafty and Mephistophelean expression when he smiles, and his whole appearance and manner have a sort of Jesuitical elegance and ease.

His hands are very narrow, with long and slender fingers that look as if they had twice as many joints as other people’s. They are so flexible and supple that it makes you nervous to look at them.

Anything like the polish of his manner, I never saw. When he got up to leave the box, for instance, after his adieux to the ladies, he laid his hand on his heart and made his final bow,—not with affectation, or in mere gallantry, but with a quiet courtliness which made you feel that no other way of bowing to a lady was right or proper. It was most characteristic.

Liszt didn’t actually think of himself as a teacher.

Sophie Menter

He asked me if I had been to Sophie Menter’s concert in Berlin the other day.

I said yes. He remarked that Miss Menter was a great favourite of his…

I asked him if Sophie Menter was a pupil of his. He said no, he could not take the credit of her artistic success to himself.

I heard afterwards that he really had done ever so much for her, but he won’t have it said that he teaches!

Later, Fay writes:

He says “people fly in his face by dozens,” and seems to think he is “only there to give lessons.”

He gives no paid lessons whatever, as he is much too grand for that, but if one has talent enough, or pleases him, he lets one come to him and play to him.

Liszt inspired and encouraged his pupils to develop their own artistic identities.

Nothing could exceed Liszt’s amiability, or the trouble he gave himself, and instead of frightening me, he inspired me. Never was there such a delightful teacher! and he is the first sympathetic one I’ve had.

You feel so free with him, and he develops the very spirit of music in you. He doesn’t keep nagging at you all the time, but he leaves you your own conception.

Now and then, he will make a criticism, or play a passage, and with a few words give you enough to think of all the rest of your life.

There is a delicate point to everything he says, as subtle as he is himself. He doesn’t tell you anything about the technique. You must work this out for yourself.

When I had finished the first movement of the sonata, Liszt, as he always does, said “Bravo!”

Yuja Wang Plays Liszt Sonata B minor

Liszt was a difficult artist to turn pages for because he sight-read so quickly.

He made me come and turn the leaves. Gracious! how he does read!

It is very difficult to turn for him, for he reads ever so far ahead of what he is playing, and takes in fully five bars at a glance, so you have to guess about where you think he would like to have the page over.

Once I turned it too late, and once too early, and he snatched it out of my hand and whirled it back.

Top 10 Hardest Liszt Pieces for Piano

We know exactly what Liszt’s quarters in Weimar looked like.

It is so delicious in that room of his! It was all furnished and put in order for him by the Grand Duchess herself.

The walls are pale grey, with a gilded border running round the room, or rather two rooms, which are divided, but not separated, by crimson curtains.

The furniture is crimson, and everything is so comfortable—such a contrast to German bareness and stiffness generally.

A splendid grand piano stands in one window (he receives a new one every year). The other window is always wide open and looks out on the park.

There is a dove-cote just opposite the window, and the doves promenade up and down on the roof of it, and fly about, and sometimes whirr down on the sill itself. That pleases Liszt.

His writing table is beautifully fitted up with things that all match. Everything is in bronze – ink-stand, paper-weight, match-box, etc., and there is always a lighted candle standing on it by which he and the gentlemen can light their cigars.

There is a carpet on the floor, a rarity in Germany, and Liszt generally walks about, and smokes, and mutters (he can never be said to talk), and calls upon one or other of us to play.

Liszt was fully aware of how his charisma affected his audiences.

Liszt knows well the influence he has on people, for he always fixes his eyes on some of us when he plays, and I believe he tries to wring our hearts.

When he plays a passage and goes pearling down the keyboard, he often looks over at me and smiles to see whether I am appreciating it.

Liszt enjoyed telling people about the time that Chopin put on a wig to impersonate him.

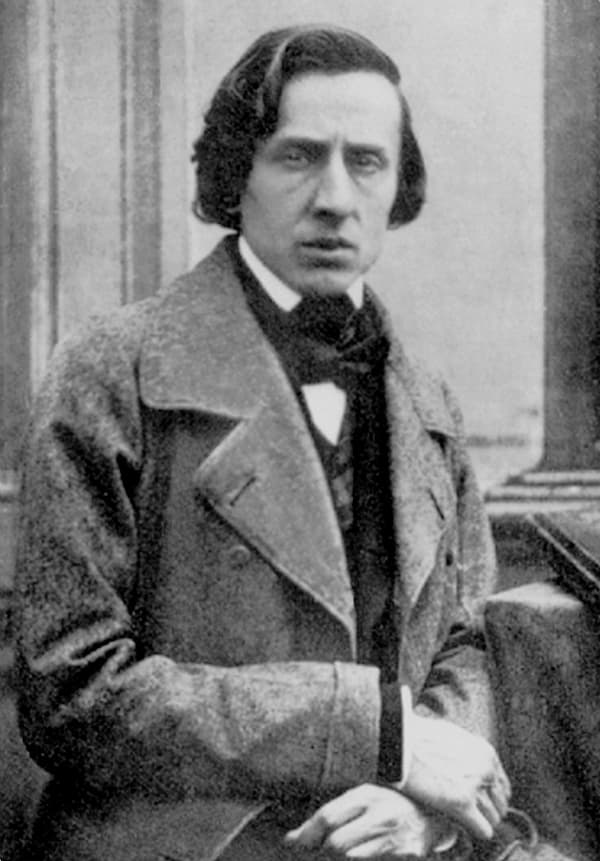

Frédéric Chopin

It was the first time I ever heard Liszt really talk, for he contents himself mostly with making little jests. He is full of esprit.

We were speaking of the faculty of mimicry, and he told me such a funny little anecdote about Chopin.

He said that when he and Chopin were young together, somebody told him that Chopin had a remarkable talent for mimicry, and so he said to Chopin, “Come round to my rooms this evening and show off this talent of yours.”

So Chopin came. He had purchased a blonde wig (“I was very blonde at that time,” said Liszt), which he put on, and got himself up in one of Liszt’s suits.

Presently an acquaintance of Liszt’s came in, Chopin went to meet him instead of Liszt, and took off his voice and manner so perfectly, that the man actually mistook him for Liszt, and made an appointment with him for the next day—”and there I was in the room,” said Liszt. Wasn’t that remarkable?

Liszt / Chopin: Six Polish Songs

Liszt actually played wrong notes, but he enjoyed doing so, and knew how to get out of them.

Liszt sometimes strikes wrong notes when he plays, but it does not trouble him in the least. On the contrary, he rather enjoys it.

He reminds me of one of the cabinet ministers in Berlin, of whom it is said that he has an amazing talent for making blunders, but a still more amazing one for getting out of them and covering them up.

Of Liszt the first part of this is not true, for if he strikes a wrong note it is simply because he chooses to be careless. But the last part of it applies to him eminently.

It always amuses him instead of disconcerting him when he comes down squarely wrong, as it affords him an opportunity of displaying his ingenuity and giving things such a turn that the false note will appear simply a key leading to new and unexpected beauties.

An accident of this kind happened to him in one of the Sunday matinees, when the room was full of distinguished people and of his pupils. He was rolling up the piano in arpeggios in a very grand manner indeed, when he struck a semi-tone short of the high note upon which he had intended to end.

I caught my breath and wondered whether he was going to leave us like that, in mid-air, as it were, and the harmony unresolved, or whether he would be reduced to the humiliation of correcting himself like ordinary mortals, and taking the right chord.

A half smile came over his face, as much as to say—”Don’t fancy that this little thing disturbs me,”—and he instantly went meandering down the piano in harmony with the false note he had struck, and then rolled deliberately up in a second grand sweep, this time striking true.

I never saw a more delicious piece of cleverness. It was so quick-witted and so exactly characteristic of Liszt. Instead of giving you a chance to say, “He has made a mistake,” he forced you to say, “He has shown how to get out of a mistake.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter