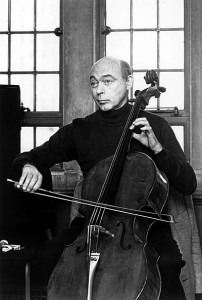

When we think about the wonders of the world, we think in terms of natural marvels or edifices. Typically, we don’t think in these terms when we describe creative artists but Janos Starker, qualifies. Virtuoso cellist, master pedagogue, articulate advocate and visionary, Starker has had an extraordinary impact on cello playing and music making. He has performed on virtually every continent. His discography numbers over 165 works on a host of recording labels, and he has been a professor at Indiana University since 1958 holding the title of Distinguished Professor.

Starker was born in Budapest, Hungary – which certainly contributed to my father’s keen interest in my studying with him. Starker’s cello lessons began at age six, he was teaching by the time he was eight and he was performing at age eleven! I actually came across a photo of Starker as a little wunderkind, playing cello in short pants. I know my mother had a crush on him.

Like my parents, Starker studied at the famed Franz Liszt Academy. Emerging from the cinders of World War II, he immigrated to the U.S. in1948 becoming principal cello of first, the Dallas Symphony, then the Metropolitan Opera and finally the Chicago Symphony. I am certain that Starker’s experience in the orchestral world gave him a unique perspective. He experienced first hand the grueling schedules and the challenges of orchestral playing, while savoring the rich symphonic repertoire. Sometimes, I am able to hunt down old recordings of the Chicago Symphony with the legendary (Hungarian) conductor Fritz Reiner. When there is a cello solo I can immediately recognize Starker’s silken sound and pristine technique.

I remember Starker telling me that his first recordings of the Six Bach Suites for Solo Cello were recorded in the wee hours of the morning after Metropolitan Opera performances. What stamina that took!

Starker had a great affinity for his fellow Hungarian composers especially the musical giants Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály. Starker’s trademark piece, the famous Kodály Solo Sonata in B minor, is unlike anything you have ever heard – a technical tour de force. The demands start with scordotura tuning – literally, “mistuning.” Kodály requires the cellist to tune down the bottom cello strings from the usual G and C, to F♯ and B, to emphasize the key with recurring B-minor chords. I vividly remember hearing Starker perform the work. The flashy double note trills and hair-raising passagework was so mesmerizing that I was moved to tears.

Starker had the crème de la crème of students to pick from. How did he choose?

Starker ‘s first criterion for selecting a student was that he or she would need to be able to assimilate a great deal of information in a compressed amount of time.

Secondly, he selected students geographically. “Spreading the word” was his fondest wish. He hoped that by choosing students from all parts of the globe, cello playing and teaching would improve exponentially. My class consisted of a motley crew of cellists from diverse backgrounds and countries far afield: Germany, Japan, Israel, the U.S. and Canada (me).

In his heyday, when I was his student, he would teach intensively for several weeks and then poof! He would be off on a three-month concert tour. During the time he was at IU, we had three lessons a week and each lesson had to be different repertoire. The pressure was tremendous. We would cower outside his massive metal studio door, taking deep breaths to calm our nerves before entering the sanctum. I remember that after each lesson, as soon as the studio door closed behind me, I would plop myself down on the floor in the hallway, right by his door, and furiously take notes so as not to forget one gem, knowledge which I would need weeks (or years) to assimilate.

Starker had many attributes but the three that most impressed us were evident during the three-hour Saturday master classes, required of course.

He could play anyone’s cello and sound perfect, whether it was a poor quality instrument or a cello that was seriously out of adjustment.

He could play any and every cello work flawlessly and from memory, picking up the piece midstream.

Most astonishing for us, was that Starker always had a cigarette burning. He’d hold it between the fingers of his right hand (his bowing hand.) His arm moved swiftly back and forth as he demonstrated. The cigarette butt would burn. The ash would grow, expanding precariously but somehow suspended. We watched in horror, our eyes following the bow back and forth like watching a tennis ball lob back and forth over the net, anticipating that the hot ash would fall on his Strad. Unfailingly, at just the right moment when the ash was impossibly long, he’d flick the butt into the ashtray. None of us dared react.

As a teacher Starker could be critical, demanding, sarcastic and intimidating but if you worked hard (and we did) he was inspiring, although compliments were rare. “You play on a very high level” was superlative praise from Starker.

Starker was determined to give us the tools to be consummate craftsmen on the cello as a means to the end: to be slavishly dedicated to the musical intentions of the composer.

One of the attributes I admire most now, is that Starker discouraged ego. There was never an inkling of favoritism. Camaraderie was cultivated even between the demigod and the underlings. Starker was compelling, and provocative as a teacher. He ignited a lifelong spark within us to excel as cellists and musical ambassadors.

Photo : http://www.bruceduffie.com/starker.html

Janos Starker – Bach Cello Suite 3 I. Prelude

Janos Starker – A Lesson in Music

Janos Starker – Kodály Cello Solo Sonata II. Mvt

Thanks Paul. Believe it or not singing while one plays or conducts ( even if it isn’t in tune!) or grunting does offer some hearing protection if you are without ear plugs. So they were quite right!

Janet – Thank for for another wonderfully written article. I truly enjoyed reading about such a tremendous figure in such a personal manner. What particularly struck me was Starker’s desire to spread his knowledge globally for the benefit of the larger community of cellists (and cellists-in-training); his emphasis on hard work and lack of ego were equally admirable.

I’ve heard so much about Starker, and none revealed the students’ perspectives. Thanks, very interesting!

Terrific article Janet. Brought back very vividly my years at IU. Thank you!

I did know about Starker’s years playing in orchestras and at the Met. Fascinating.