Dresden, with its well-known Sächsische Staatskapelle, Kreuzchor and Semper Opera House, cannot only be considered one of the great ‘musical’ cities in Germany, but most importantly, its cultural and political milieu played a significant role in the musical and artistic education of one of the greatest opera composers of the 19th century, Richard Wagner.

Parsifal

Act III Prelude

Richard Wagner was born in Leipzig on May 22, 1813. The following year, his mother and step-father, Ludwig Geyer, a friend of the Romantic composer Carl Maria von Weber, moved the family to Dresden. Even as a young boy, Wagner was attracted to the stage, not only attending performances in Dresden’s opera house on a regular basis, but on the occasion of a royal wedding, and in the performance of Weber’s ‘Festspiel’ (play) “The Vineyard on the Elbe”, even appearing on stage. In December 1822, the young Wagner was accepted into the ‘Kreuzschule’, whose choir, already well known in its day (and still world-famous today), he heard on a daily basis. Attending services in the Kreuzkirche (Church of the Cross), he also heard the famous “Dresdner Amen”, which would later reappear as a musical ‘Leitmotif’ in his opera “Parsifal”. Not only would opera and stage influence Wagner, but the very essence of the city of Dresden itself — its architecture, its royal collections in the Zwinger Museum, in the Grünes Gewölbe (Green Vault) and in the Porcelain Palace — would provide an important and formative backdrop for his artistic development.

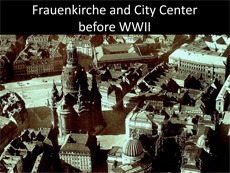

Throughout its history, Dresden had played a major role as capital of Saxony, home to one of the Electors of the Holy Roman Empire, and also to the kings of Saxony and Poland, August the Strong (1676-1733) and his son Friedrich August (1696-1763). With its beautiful Renaissance and Baroque palaces, Dresden was the ‘Florence on the Elbe River’, attracting architects and painters from Italy, and musicians and craftsmen from all over Europe. August the Strong, who saw himself as a ‘Sun King’ (like Louis XIV), conceived of the city, its palaces and museums, within the Baroque concept of ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ (a concept which was later applied by Wagner in his ideas on opera and drama), in which singular elements come together to create a perfect ensemble. August the Strong’s summer residence, the Pillnitz Palace and Gardens, situated on the Elbe near Dresden, is such an example: the architecture of the palace and the magnificent park and garden work in unison; beautiful pavilions, fountains, trees, fragrant plants and flowers stimulate all the senses. Another example is the Frauenkirche (Church of Our Lady) in Dresden, whose architect Georg Bähr conceived the church as the radiating center of the old city, with all adjacent architecture relating to it and to each other. The greatest Baroque organ builder, Gottfried Silbermann, also from Saxony, built its famous organ (lost in WWII), which J.S. Bach played “to test its lungs”. August the Strong was also the founder of the Dresdner Hofkapelle (Court Orchestra), known today as the Sächsische Staatskapelle (Saxon State Orchestra), which attracted many composers and musicians from all over Europe. As its conductor, Wagner considered the orchestra the ‘Wunderharfe–the Wondrous Harp’.

Throughout its history, Dresden had played a major role as capital of Saxony, home to one of the Electors of the Holy Roman Empire, and also to the kings of Saxony and Poland, August the Strong (1676-1733) and his son Friedrich August (1696-1763). With its beautiful Renaissance and Baroque palaces, Dresden was the ‘Florence on the Elbe River’, attracting architects and painters from Italy, and musicians and craftsmen from all over Europe. August the Strong, who saw himself as a ‘Sun King’ (like Louis XIV), conceived of the city, its palaces and museums, within the Baroque concept of ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ (a concept which was later applied by Wagner in his ideas on opera and drama), in which singular elements come together to create a perfect ensemble. August the Strong’s summer residence, the Pillnitz Palace and Gardens, situated on the Elbe near Dresden, is such an example: the architecture of the palace and the magnificent park and garden work in unison; beautiful pavilions, fountains, trees, fragrant plants and flowers stimulate all the senses. Another example is the Frauenkirche (Church of Our Lady) in Dresden, whose architect Georg Bähr conceived the church as the radiating center of the old city, with all adjacent architecture relating to it and to each other. The greatest Baroque organ builder, Gottfried Silbermann, also from Saxony, built its famous organ (lost in WWII), which J.S. Bach played “to test its lungs”. August the Strong was also the founder of the Dresdner Hofkapelle (Court Orchestra), known today as the Sächsische Staatskapelle (Saxon State Orchestra), which attracted many composers and musicians from all over Europe. As its conductor, Wagner considered the orchestra the ‘Wunderharfe–the Wondrous Harp’.

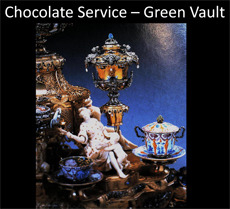

As a ‘Baroque’ collector, August the Strong assembled an enormous and diverse collection of clocks, armor, tools, Chinese and Japanese porcelain, jewels and other precious objects which attracted many artists and craftsmen as well as the general public. The ‘Grünes Gewölbe’ (Green Vault), in which many of these objects were housed, was of his own personal conception and design. Under his supervision, in 1703 Böttger, a chemist and alchemist who was initially in search of the secret of producing gold, discovered hard porcelain, the “white gold”, which led to the establishment of the famous Meissen factory and would bring enormous wealth and renown to the Saxon court.

As a ‘Baroque’ collector, August the Strong assembled an enormous and diverse collection of clocks, armor, tools, Chinese and Japanese porcelain, jewels and other precious objects which attracted many artists and craftsmen as well as the general public. The ‘Grünes Gewölbe’ (Green Vault), in which many of these objects were housed, was of his own personal conception and design. Under his supervision, in 1703 Böttger, a chemist and alchemist who was initially in search of the secret of producing gold, discovered hard porcelain, the “white gold”, which led to the establishment of the famous Meissen factory and would bring enormous wealth and renown to the Saxon court.

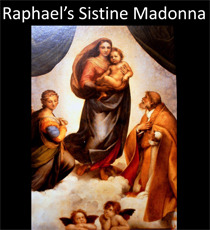

The son of August the Strong, Friedrich August, a connoisseur of fine art, assembled the famous collection of the Zwinger Museum consisting of many of the Renaissance and Baroque paintings of Old Masters. Over the following centuries, the Zwinger collections and Dresden’s Art Academy would attract many painters and art students from all over Europe.

The son of August the Strong, Friedrich August, a connoisseur of fine art, assembled the famous collection of the Zwinger Museum consisting of many of the Renaissance and Baroque paintings of Old Masters. Over the following centuries, the Zwinger collections and Dresden’s Art Academy would attract many painters and art students from all over Europe.

Rienzi

Ouverture

Wagner’s family left Dresden for Leipzig in 1828, but he returned in 1837 for a short stay; there he read the novel “Rienzi” by Edward Bulwer Lytton, which inspired him to write his tragic opera of the same name. In the following years, Wagner lived in many different cities, including Würzburg, Magdeburg, Königsberg, Riga and Paris, to further his musical career, but he returned to Dresden in 1842 for the first presentation of that opera—a presentation facilitated by Weber’s widow, Caroline. In his letter to Robert Schumann, Wagner wrote: “I have chosen Dresden for its première presentation — rather than Berlin, where I had the same chances, because I can count on a better reception there than in Berlin”. “Rienzi” became a triumph in Dresden, followed there by “The Flying Dutchman”. Wagner was nominated as Dresden’s ‘Hofkapellmeister’ (Court Conductor). He encouraged the presentation of German and French operas, and supported the ‘Musikfest’ (music festival) of Saxon Men’s Choirs, which culminated in a concert in the Frauenkirche in July 6, 1843: one hundred orchestra musicians played in the church rotunda and twelve hundred singers sang ‘Das Liebesmahl der Apostel’ (The Love Feast of the Apostles) from its balconies; this work is considered by many musicologists to be the precursor to Parsifal. That same year, Wagner met the architect Gottfried Semper, who had been commissioned to build the new Opera House, engaging in long discussions with him about ‘ideal’ theater architecture, again inspired by Baroque concepts. On October 19, 1845, Wagner’s ‘Tannhäuser’ had its premiere in the Semper Opera House.

Das Liebesmahl der Apostel

Das Liebesmahl der Apostel

The politically turbulent year of 1848 — the year of the March Revolution — saw Wagner “the revolutionary” espousing the ideas of the republican reform movement in Saxony, where he met the Russian anarchist Michail Bakunin. Compared to other German states, Saxony had been much more ‘liberal’ throughout the centuries. For example, when silver was discovered in the ‘Erzgebirge’ (Ore Mountains), miners were allowed to work freely for themselves, only paying a tax to the court on their product; when Catholic cloisters and monasteries were dissolved after the Reformation, their buildings were turned into hospitals and the so-called ‘Prinzen Schulen’ (Prince’s Schools) — which were not for princes, but for intelligent children regardless of their social standing, their fees paid by the state.

Wagner wanted not just political change but also called for structural reforms of theater and opera. He developed his concept of the role of the arts in society and wrote the treatise “Entwurf zur Organisation eines deutschen Nationaltheaters für das Königreich Sachsen” (Outline for the Organization of a German National Theater for the Kingdom on Saxony). Writing various articles in Dresden newspapers, he called for active participation in the political revolution as well. During street fighting in Dresden in May 1849, the baroque Opera House went up in flames. The insurrection was crushed; Wagner and Semper, both of whom had actively participated, fled to Switzerland after a warrant for their arrest had been issued. Only after thirteen years, in March 1862, was Wagner granted a general pardon, allowing him to return to Saxony. Although he made only some short visits thereafter, Dresden and its culture had proven a decisive influence on Wagner’s artistic development.

In my next two articles, I will further concentrate on these early important influences as Wagner develops his mature ideas fusing opera and drama into his very own version of ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’.

Beautiful pieces! Bravo…