Flow my tears! According to various theories of personality differences, regardless whether they are based on a biological, psychological or social analysis, each human being belongs to one of four types of basic temperament, or “humours.” The Sanguine bodily temperament, taking its name from the color of blood and being associated with the season of spring and the classical element of air, corresponds to a light-hearted, spontaneous and confident personality. A phlegmatic person is calm, shy and self-content, and associated with the season of winter and the element of water. Choleric “humour” corresponds to the season of summer and the element of fire, and is said to be ambitious, passionate, energetic and bad-tempered. And finally, a melancholy temperament, being caused by an overabundance of black bile, denotes a kind and considerate human being, highly creative in poetry and art.

According to various theories of personality differences, regardless whether they are based on a biological, psychological or social analysis, each human being belongs to one of four types of basic temperament, or “humours.” The Sanguine bodily temperament, taking its name from the color of blood and being associated with the season of spring and the classical element of air, corresponds to a light-hearted, spontaneous and confident personality. A phlegmatic person is calm, shy and self-content, and associated with the season of winter and the element of water. Choleric “humour” corresponds to the season of summer and the element of fire, and is said to be ambitious, passionate, energetic and bad-tempered. And finally, a melancholy temperament, being caused by an overabundance of black bile, denotes a kind and considerate human being, highly creative in poetry and art.

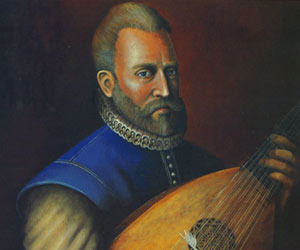

During the early 17th century in Elizabethan England, a great sense of melancholy descended upon the country. Although an excess of black bile might have been partially responsible, it is generally agreed that the primary reasons for this phenomenon were found in the religious uncertainties caused by the English Reformation. This melancholy disposition is personified in Shakespeare’s Prince Hamlet, the “Melancholy Dane,” and also appears in the poems of Thomas Browne and Jeremy Taylor, characteristically titled Urn Burial, and Holy Living and Holy Dying. In music, this phenomenon is most closely associated with John Dowland (1563-1626), who even coined his own motto “Dowland, semper dolens” (Dowland, always mourning.) Born in London, Dowland went to Paris in the service of the ambassador to the French Court in 1580. There he converted to Catholicism, but eventually returned to England in 1584. After completing his studies at Christ Church, Oxford, he personally performed for Queen Elizabeth in 1592. When one of the queen’s lutenists died in 1594, Dowland applied for the position but the Protestant court rejected his application. Embittered and frustrated Dowland left for the Continent, traveling first through Germany and subsequently to Italy to study with Luca Marenzio, the foremost madrigalist of his time. According to Dowland, he became entangled with a group of exiled English Catholics plotting to assassinate Queen Elizabeth and quickly fled to the court of the Landgrave of Hesse. In 1596 he returned to England and once again applied for a position at Elizabeth’s court, but alas, the post eluded him yet again. This renewed rejection spawned one of his most celebrated publications, The First Booke of Songes or Ayres of Foure Partes with Tableture for the Lute, of 1597. This collection of 21 strophic songs was arranged to allow performance by various combinations of singers and instrumentalists. Immediately popular, it was reprinted at least five times and substantially revised by the composer in 1606. It also inspired the poet Richard Barnfield to pen a sonnet in praise of Dowland:

If music and sweet poetry agree,

As they must needs, the sister and the brother,

Then must the love be great ‘twixt thee and me,

Because thou lovest the one, and I the other.

Dowland to thee is dear, whose heavenly touch

Upon the lute doth ravish human sense;

Spenser to me, whose deep conceit is such

As, passing all conceit, needs no defence.

Thou lovest to hear the sweet melodious sound

That Phoebus’ lute, the queen of music, makes;

And I in deep delight am chiefly drown’d

When as himself to singing he betakes.

One god is god of both, as poets feign;

One knight loves both, and both in thee remain.

DOWLAND, J.: Lachrimae (Fretwork)

By 1598, Dowland was in the services of Christian IV of Denmark, but was dismissed for insubordination in 1606. During that time, he published his second and third Book of Songs or Ayres, and also his Lachrimae or Seaven Teares, a consort work of great originality. Each of the seven Pavans starts with the famous theme taken from his Lute song Flow my Tears. In this most celebrated instrumental composition of the late Renaissance — scored for four viols and lute — Dowland was once more inspired by a deeply felt tragic concept of life, and a preoccupation with tears, sin and death, stemming from his failure to secure a post at the English court. Eventually he did win an appointment as lutenist at the court of James I in 1612, but oddly, inspiration seems to have deserted him once he had achieved his life’s ambition. He only managed to publish four more attributable settings before his death in 1626. It stands to reason that securing one’s dreams somehow balances the amount of black bile running through your body; good for your career but not really helping your creative side!

Flow my Tears