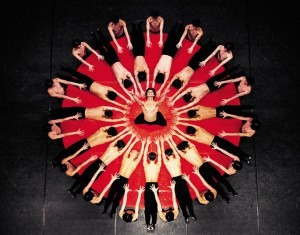

Maurice Béjart’s Boléro

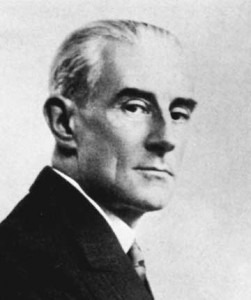

Music lovers and musicians adore the music of Frenchman Maurice Ravel. Whether it’s his moving Pavane for a Dead Princess or his more esoteric String Quartet, his colorful orchestral work La Valse or his dazzling piano concertos (one of which is for the left hand only), he was considered an innovative and inventive composer of the impressionist period along with his co-patriots Debussy and Fauré.

One of his most famous pieces is Boléro — a one-movement orchestral piece. Ravel originally composed the work as a ballet commissioned by the Russian ballerina Ida Rubinstein. Ravel decided to try something new and controversial with this piece —to use one insistent melody with a recurring incessant rhythm.

The première at the Paris Opéra in 1928 was a sensation. Choreographed by Nijinska, a gypsy dances on a table surrounded by men in an inn in Spain — a stunning and seductive theatrical experience. Choreographer Maurice Béjart’s “Bolero” is one of his most well-known and popular ballets. In 1979 he decided to have a man dance the central character surrounded by women. There is a third version consisting of all men. The impact of the work is quite different as the gender changes.

Boléro is frequently performed as an orchestral piece. Boléro’s hypnotic snare drum beat and inexorable climax never fails to bring the house down. How does Ravel achieve this with merely one melody and one continuous rhythm?

Ravel: Boléro – A Detailed Analysis

Ravel — a master of orchestral textures and effects — has each instrument and then groups of instruments introduce the melody. Subtly, Ravel builds the piece not by developing his melodic idea, or his rhythm, but by adding instruments, which builds to an incredible climax.

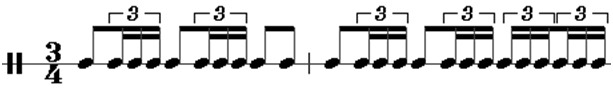

Boléro begins with a two-bar, 24-note beat pattern in the snare drum at an almost inaudibly quiet dynamic. Poor snare-drum player! This pattern continues throughout the entire 430 bars of the piece playing unwaveringly steady in tempo gradually reaching fff or fortississimo (or as loud as possible!) That adds up to an amazing 5,144 drum strokes. What a feat!

The expressive melody is superimposed on this rhythm and repeated, changing in character due to the quality of sound produced by the various instruments that play it.

This piece is a great way to get to know the instruments individually.

The first to enter with the melody is the flute—it’s golden tones quite recognizable. The sparse accompaniment begins with plucked strings (pizzicato) punctuating each beat of the bar. The strings play this figure virtually for the entire work!

The clarinet enters next followed by the bassoon playing the melody in quite a high register (for a bassoon.)

Maurice Ravel

Can you guess what the next instrument is? 1. ____________ (hint: it is a high-pitched woodwind instrument, the little sister of the second instrument that played.)

An instrument rarely featured is next. Hear the sweet and unique sound of the oboe d’amore — a double reed instrument in the oboe family. Unlike the oboe, it has a pear-shaped bell at the bottom of the instrument. While it is the mezzo-soprano of the oboe family, lower and deeper than the oboe, the English horn is the alto, the largest and lowest sounding of the three instruments. It appears later in the piece.

The tenor saxophone, rare in a symphony orchestra piece, adds to the jazzy feel of the work. Soon another saxophone enters with the melody — the 2. __________________.

Ravel starts intensifying the melody with the entry of the horn, two piccolos and the celeste which has a bell like quality but it is a 3. ______________instrument. Unusually enough, while the horn plays the melody in the original key, Ravel has the celeste and two piccolos play it in two different keys.

Later, an American composer uses this technique. In fact, often he put different melodies together in different keys. Can you name him? 4. _____________________

The next entry of the melody is a great opportunity to see the relative sizes of the oboe, oboe d’amore, and English horn and to hear them together.

Perhaps the wildest version of the melody is the “jazzed” up trombone rendition. At this late point in the piece the “singers” of the orchestra, the violins, finally enter with the melody. Using mainly the higher instruments, Ravel builds the suspense.

The snare drum player gets reinforcement as a second snare drum is added. Soon the entire orchestra is playing with all their might. There is a sudden surprise just before the end. Ravel aurally shocks us by switching the key briefly.

With great fanfare, the bass drum, cymbals and tam-tam enter just six bars from the end. Watch as the trombones move their instrument slides toward their faces. This raucous sound is called “glissandos” or glides. Ravel holds us captive for a moment on a dissonant and remote chord at the very end before the great finish.

When the famous Italian Maestro Arturo Toscanini conducted the work, he pushed the orchestra to accelerate to the end. Ravel was miffed. The tempo was too fast for Ravel. No one dared criticize the conducting of Maestro Toscanini! Toscanini thought that what he did “saved” the piece. But Ravel insisted, “I don’t ask for my music to be interpreted, only that it should be played.” Their exchange of letters back and forth arguing the merits of a faster tempo became a public battle of wills.

Ravel was quite perplexed by Boléro’s success. For him it was experimental and “a piece for orchestra without music.” Boléro even made it to Hollywood in the 1979 comedy “10” starring Dudley Moore, Julie Andrews and Bo Derek. It was a trend-setting film and a huge hit, catapulting Moore and Derek into stardom. Whether a woman was a “10” became the measure of a woman’s sex appeal in popular culture.

To this day, the work is always a hit. Ravel would have been surprised.

Best Boléro Performances

Here are some of the best Boléro performances across centuries, including Maurice Béjart’s ballet, orchestral performances with conductors.

Boléro: Choreography by Maurice Béjart (Maya Plisetskaya)

Boléro Conducted by Daniel Oren

Boléro Conducted by Kent Nagano

Boléro Conducted by Alondra de la Parra

Boléro Conducted by Christoph Eschenbach

Boléro Conducted by Gustavo Dudamel

Boléro Conducted by Georges Prêtre

Boléro Conducted by Sergiu Celibidache

What is your best Boléro version? Let us know.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

QUIZ ANSWERS

1. E-flat clarinet

2. soprano saxophone

3. keyboard

4. Charles Ives

There is a problem with the numbers mentioned. The 5114 drum stroke count is possibly wrong or misleading and the number of bars (430) is also incorrect. Since the 24-stroke drum pattern is two bars long, that should mean 215 repeats of this rhythmic motif; 215 * 24 = 5160. But that is also wrong.

The snare drum motif notated has 24 strokes and is played 9 times per melodic phrase (the phrase is 16 bars long plus a two-bars bridge of only the drum and other supporting instruments playing the same pattern). So each melodic repeat has 9 rhythmic patters, 9 * 24 = 216 strokes.

The melody in two forms (C-major and deviating to Phrygian mode), and aside from the closing modulation in the coda, repeats 17 times. 9 drum patterns of 2 bars each is 18 bars, 18 * 17 = 306 bars. The coda has 15 repeats of the pattern (30 bars) plus the final bar bringing the total to 337 bars. (That’s close to 340, perhaps the digits got reversed from 340 to 430).

So 9 drum patterns per melodic phrase times 17 melodic phrases = 152, times 24 strokes per pattern = 3672 strokes up to the coda. Add the coda of 15 patterns * 24 and you have 360 more strokes . 3672 + 360 = 4032. There are 8 additional strokes in the final closing bar, bringing the total to 4040.

What I have not counted is the added drum strokes where two snare drums play the same pattern balancing the increasing volume of the build-up. I don’t have the score handy to see where a second drum enters and doubles the first. That could be where the 5114 number comes from. If I add 4032 + 216 * 5 (i.e., five phrases doubled by a second drummer) I get 5112, so this appears to be close enough to speculate that the count is of ALL drum strokes. Still the count of measures (bars) was wrong.

Most analysis accepts Ravels thesis that this is not about the melody but about the setting. Of course that is the obvious and most outstanding fgeature. But he may well have touched on a whole other area about repition, recurrance or iteration. An idea that Shostakovitch saw and used in the way that the seventh’s “Invasion Theme” could be said to be about the quotidian, repetitive and evolving nature of repression. How simple repetion and evolution can create a monster.

We are built on iteration; our bodies, our daily rhythms, sex (as in 10), seasons, careers, eating, relationships. I think my point that is missed is that the 2 melodies also have a something itterative about them and seem to have been well created to bear the repition. And for analysis answering the question “how that is?” would be really interesting. Both themes carry a sense of repeated evolution. They contrast very well. How do they do all that? What is it about them that allows them to carry such repition?

I don’t think a theme like Mozart – Piano Sonata No. 16 in C Major, K.545 (1st Mvt) in all it’s sweetness could cary that amount of frieght. So how did Ravel do that? How did he turn out something that would appeal to Shostakovitch to copy the idea in one of his most personal and powerful works?

The impression I get from the music reminds me of a snake crossing a tiled surface , an iteration and freedom competing and maybe that is somethign that appealed to in Shozzy 7. In Bolero the drum theme and sinuous A and B themes. I just feel like there is a lot more going on than the analyses suggest.

Any thoughts?