Composed in January and February 1920, Paul Hindemith’s third string quartet was described as “brimming with youthful energy…a thrilling, musical event, real ‘new’ music. Here everything is comprehensible and concrete.” First performed at the Donaueschingen Chamber Music Performances in 1921, it led to the founding of the Amar Quartet — with Hindemith performing on the viola — since no suitable ensemble could be found which would be willing to study and perform this technically difficult work. Musically, Hindemith continued to explore and incorporate various international musical styles, and in this work he unashamedly acknowledged the coloristic stimulus of Slavic music in general, and of Béla Bartók in particular.

Composed in January and February 1920, Paul Hindemith’s third string quartet was described as “brimming with youthful energy…a thrilling, musical event, real ‘new’ music. Here everything is comprehensible and concrete.” First performed at the Donaueschingen Chamber Music Performances in 1921, it led to the founding of the Amar Quartet — with Hindemith performing on the viola — since no suitable ensemble could be found which would be willing to study and perform this technically difficult work. Musically, Hindemith continued to explore and incorporate various international musical styles, and in this work he unashamedly acknowledged the coloristic stimulus of Slavic music in general, and of Béla Bartók in particular.

Paul Hindemith: String Quartet No. 3 in C major, Op. 16, “Adagio”

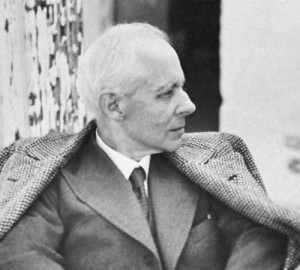

The pianist, composer and music ethnologist Béla Bartók (1881-1945) wrote numerous books and articles on the folk music he collected. He also published various collections of nearly two thousand traditional tunes he meticulously recorded on multiple field trips. It was his extensive study of Hungarian, Bulgarian, Romanian, Slavic and Arabic music, which he began as a young man and continued to the end of his career that decisively shaped and influenced his compositional style. His personal style ingeniously merged these folk influences with contemporary movements and trends, ultimately achieving a unique synthesis in his music. With his first violin sonata, a work Hindemith publicly performed and admired, Bartók extended the limits of dissonance and tonal ambiguity while giving voice to the sonic landscape of Eastern Europe.

Béla Bartók

If Hindemith’s third string quartet looked decidedly towards Eastern Europe for inspiration, his Kammermusik No. 1 aligned himself with Igor Stravinsky, Darius Milhaud and the futurist manifesto of the Parisian avant-garde. Particularly the concluding movement, “Finale: 1921,” which cites a contemporary foxtrot and makes use of a siren, attracted special attention. At first hearing, Alfred Heuss reported, “A hissing and seething begins, a pushing, shoving, and pulling, screams and shouts assault our ears; one sees sensuously distorted, common faces, hears whipping and blowing, laughter and shouts, groaning and rejoicing, whistling and yelling; pairs mingle in the most lascivious manner in what are literally foxtrot melodies, barbaric sounds of half-engrossed, giddily reeling people are uttered. At the conclusion there is a long, all-penetrating whistle, probably a warning that the piece is to be brought to an end — and fast!”

Paul Hindemith: Kammermusik No. 1, Op. 24a, “Finale: 1921”

The incorporation of a foxtrot into a work bearing the title Kammermusik (Chamber Music) was indeed shocking, but had already been prefaced by a composition that combined the theme from J. S. Bach’s Fugue in C minor, BWV 847 with a rather noisy ragtime. Composed for orchestra during Easter 1921, Hindemith addressed his critics as follows: “Do you think that Bach is turning in his grave? He wouldn’t think of it! If Bach were alive today, he might perhaps have invented the shimmy or at least incorporated it into respectable music. Perhaps he too would have taken a theme from the Well-Tempered Clavier of a composer who represented Bach to him.”

Paul Hindemith: Rag Time [well-tempered]

Paul Hindemith

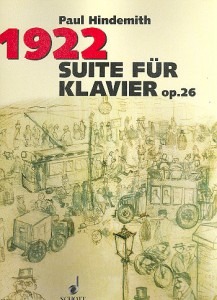

Paul Hindemith: Suite 1922

Although Hindemith continued to sporadically make use of jazz elements, his musical style — as a result of his employment at Donaueschingen — changed to draw strength from the gestures and aesthetic of the high Baroque. I tell you more about that in our next episode.