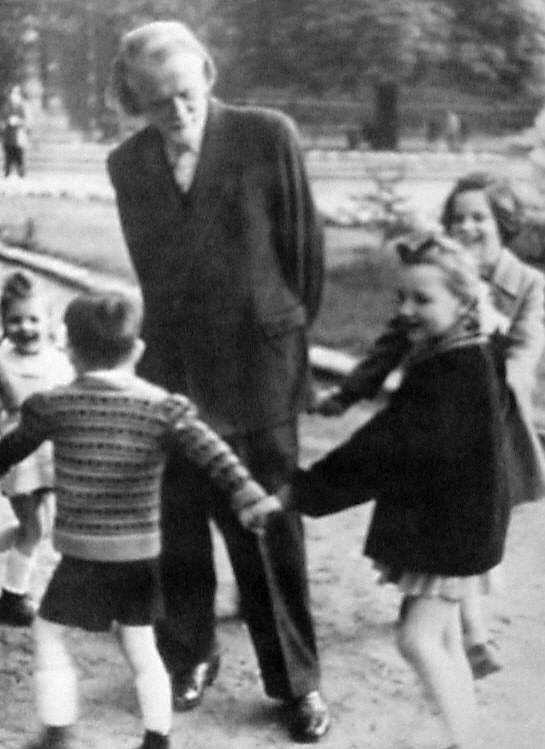

Zoltán Kodály with children

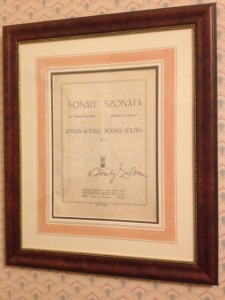

When I walk into my music studio I see Zoltán Kodály’s Sonata for Cello and Piano. It is prominently displayed and beautifully framed with Kodály’s signature splashed across the title page. Kodály was an important figure in our house. He was one of my father’s teachers at the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest in the 1930’s and was then, as now, considered one of the gods of Hungarian composers. I remember meeting him as a child. He obviously loved children. He bent right down to say hello to me. I remember his flowing white hair, white beard and startlingly blue eyes.

Zoltán Kodály: Sonata for Solo Cello, Op. 8 (János Starker, cello)

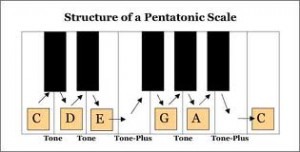

Today, I know his music well. His Duo for Violin and Cello and his Solo Sonata for cello are mainstays of any cellist’s repertoire, especially for anyone who studied with János Starker! But Kodály wrote a number of choral and orchestral works. The best known are the Háry János Suite, Dances from Galánta and Psalmus Hungaricus — a choral work for tenor, chorus and orchestra written in celebration of the unification of Buda and Pest on either side of the Danube. Kodály conducted the work in London in 1927 and subsequently, the piece was more widely heard when the illustrious maestros Toscanini and Mengelberg conducted it. In Psalmus Hungaricus Kodály integrates folk-like pentatonic tidbits. Although it is one of his masterworks it is rarely performed outside of Hungary.

Today, I know his music well. His Duo for Violin and Cello and his Solo Sonata for cello are mainstays of any cellist’s repertoire, especially for anyone who studied with János Starker! But Kodály wrote a number of choral and orchestral works. The best known are the Háry János Suite, Dances from Galánta and Psalmus Hungaricus — a choral work for tenor, chorus and orchestra written in celebration of the unification of Buda and Pest on either side of the Danube. Kodály conducted the work in London in 1927 and subsequently, the piece was more widely heard when the illustrious maestros Toscanini and Mengelberg conducted it. In Psalmus Hungaricus Kodály integrates folk-like pentatonic tidbits. Although it is one of his masterworks it is rarely performed outside of Hungary.

The Háry János Suite includes a traditional Hungarian instrument called the cimbalom, frequently used in Hungarian gypsy bands. It closely resembles a hammer dulcimer and has a very unique sound. Everyone learned how to play this instrument in Hungary even my grandmother! Apparently it is quite difficult to play as the traditional cimbalom’s tuning is not systematic. It is played by striking two spoon-like beaters against the strings.

Zoltán Kodály: Háry János Suite (Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

Kodály started his musical education at a very young age. “The making of my destiny was as natural as breathing. I sang earlier than I talked and I sang more than I talked. I became acquainted with the musical instruments and classical masterpieces at an early age…I composed at the age of four…

As an adult he became very interested in researching the indigenous music of Hungary. Hungarians have lived in Central Europe since the ninth century and are a nation of singers. Their thousands of traditional songs, which were composed by anonymous poets, were preserved orally in small villages undiscovered by the outside world.

As an adult he became very interested in researching the indigenous music of Hungary. Hungarians have lived in Central Europe since the ninth century and are a nation of singers. Their thousands of traditional songs, which were composed by anonymous poets, were preserved orally in small villages undiscovered by the outside world.

Kodály believed that the art-music of the Hungarian people should be based on its folk music. The cataloguing, collecting and disseminating of this music became his life’s work. Kodály sought out the folk songs of the peasants living far from the influences of western music in the cities. With fellow Hungarian composer and close friend Béla Bartók, they hiked to remote villages to seek what they felt was the embodiment of the Hungarian spirit in the folk music, painstakingly recording the songs on phonograph cylinders. After years of collecting Kodály found that the main characteristic of the music was the use of the pentatonic scale — a scale that uses only 5 notes rather than our usual scales system of 7 notes. Many of the rhythms of the songs are also characteristically Hungarian too — the first note is the more heavily accented note in a phrase, similar to the spoken language. (In Hungarian the accent is on the first syllable of each word.) Kodály edited many volumes of these songs.

Kodály believed that everyone is capable and has a right to musical literacy. Music after all belongs to everyone. By 1929 he was determined to reform the teaching of music and to make it an integral part of education. Music education should begin with very young children all of whom can be taught musical concepts. “Let us take our children seriously! Everything else follows from this…only the best is good enough for a child.” Kodály became internationally known for his approach to music education, which became the widely taught Kodály Method.

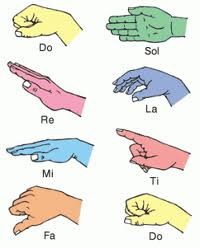

To Kodály, singing is the foundation of musical learning. Any child can learn how to sing through a simple method — using hand signals and incorporating games, movements and songs. Rhythmic movements such as walking, running, marching and clapping introduce rhythmic concepts. Kodály’s Method elevated the level of musical literacy and teaching standards. “We should read music the same way that an educated adult will read a book: in silence, but imagining the sound.”

To Kodály, singing is the foundation of musical learning. Any child can learn how to sing through a simple method — using hand signals and incorporating games, movements and songs. Rhythmic movements such as walking, running, marching and clapping introduce rhythmic concepts. Kodály’s Method elevated the level of musical literacy and teaching standards. “We should read music the same way that an educated adult will read a book: in silence, but imagining the sound.”

Kodály also emphasized the importance of using folk or native music of other countries and music of the highest artistic value. “Only art of intrinsic value is suitable for children! Everything else is harmful,” he said. He taught students at several schools whose choirs “never missed a note.” He was proud that in Hungary singing was taught every day in 120 general schools.

Today his method is still being used .If only we could adopt Kodály’s attitude everywhere so that everyone might get an education in music. We who love music know that “Music multiplies the beauty of life and all that is precious in it.”

Visit International Kodály Society and the Organization of Kodály Educators for more information.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Psalmus Hungaricus