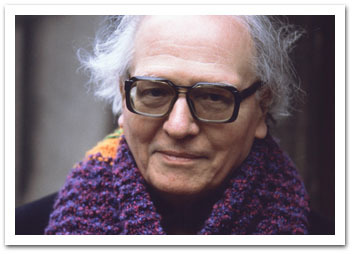

Olivier Messiaen

‘Serialism’ is actually a surprisingly broad term, used to describe a compositional technique in which your musical elements (pitch, dynamics, articulation and so on) are controlled or ordered in a certain way.

Often, many people think of ‘serialism’ as something only involving pitch, and whilst this was the most widely-used form of serialism (especially in the early days), this isn’t all there is to it. The most common way of employing a serial technique is using 12-tone composition, something with which anyone who’s studied Schoenberg’s music will be familiar. Brace yourself.

Pierre Boulez

So that we don’t just end up repeating the same melody over and over, we can manipulate our row using two main techniques: inversion, and retrograde. Retrograde simply involves playing the row in reverse order, and, put simply, inversion switches the direction of your notes – so where your tune originally rises, it falls instead, and vice versa.

When you throw in the fact that you can transpose any form of the row up or down any number of semitones, you end up with quite a lot of choice of chords and melodies. The important thing to remember is that it wasn’t supposed to sound ‘nice’; or, at least, it wasn’t the primary concern of serial composers. 12-tone technique was a way of putting a bit of control on the fact that you didn’t have to rely on the tonal system any more. Instead of having complete freedom over which pitches to use, it was a convenient way of ‘democratising’ the pitches of the scale. Often, when given complete freedom over something, it’s easy to slip back into old habits (i.e. the old tonal system). 12-tone technique ensured that this didn’t happen by making all 12 notes equal to each other.

Arnold Schoenberg

Ok, so some serial pieces were more successful than others. It soon became apparent that serialism was more something to be found and analysed in a score – it’s pretty impossible to pick out which inversion or retrograde of something you’re hearing in a performance of Schoenberg’s Five Piano Pieces Op.23. However, there’s still some very expressive music to be found out there, and while serialism wasn’t going to become the new norm in composition, it was nevertheless a very important step forward in the history of 20th-century music. By the end of the 19th century, there was a feeling among many composers that they needed to escape from the confines of the hyper-expanded tonality of the 19th century. Their new experiments were an important milestone in the 20th century’s development of new styles of composition, and although you might not be able to kick back and relax to Boulez just yet, the fact remains that serialism’s influence was incredibly important in shaping the course of music history.