Teaching must be one of the most hazardous professions worldwide. And I am not necessarily talking about public schools in Angola, Los Angeles or the Bronx. Nor am I talking about bulletproof glass, metal detectors or semi-automatic weapons. There are many more subtle ways of getting back at your teacher. Just ask Ignaz Schuppanzigh (1770-1827) who became Ludwig van Beethoven’s violin teacher in 1794.

© Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien

Schuppanzigh started his musical career as a viola player, but switched to the violin in his teens. Although a particularly handsome youth, the outstanding violist, violinist and conductor became morbidly obese in adult life. Toward the end of his life, Schuppanzigh’s fingers reputedly grew so fat that he was unable to play in tune. None withstanding his corpulent frame, Schuppanzigh was the leader of Prince Lichnowsky’s private string quartet, undoubtedly the first professional ensemble of its kind.

When Beethoven first arrived in Vienna in November 1792, he studied composition with Joseph Haydn, at that time Europe’s most famous composer. His lessons with Haydn abruptly terminated in 1794 when the old master left for his second visit to London. Since Beethoven now had a bit of spare time, he engaged Schuppanzigh for violin lessons. Beethoven reported that he went there three times a week, but there is no indication as to the duration of the student-teacher relationship. We do know, however, that they became fast friends, and that the Beethoven String Quartets Op. 18, commissioned by his benefactor and patron Prince Lobkowitz, were first performed by the Schuppanzigh quartet.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Lob auf den Dicken, WoO. 100 (Berlin Singakademie; Dietrich Knothe, cond.)

By 1808, Count Razumovsky commissioned Schuppanzigh to assemble the finest string quartet in Europe, providing Beethoven not only a superb performance medium but also the opportunity to fine-tune his compositions. Given the technical challenges of Beethoven’s late string quartets, the musical expertise of the Schuppanzigh quartet became invaluable. Clearly, these works cannot be performed without numerous dedicated rehearsals, and more than once Schuppanzigh complained to Beethoven about a particularly difficult passage. Apparently Beethoven brushed off the violinist by remarking, “Do you believe that I think about your miserable fiddle when the muse strikes me?” On occasion, tempers must have been frayed, because in 1801 Beethoven composed a short choral piece entitled “Lob auf den Dicken” (In Praise of the Fat One) WoO 100, for Schuppanzigh:

| “Schuppanzigh ist ein Lump. Wer kennt ihn nicht, den dicken Sauermagen, den aufgeblasnen Eselskopf? O Lump Schuppanzigh, o Esel Schuppanzigh, wir stimmen alle ein, du bist der größte Esel, o Esel, hi hi ha.” | Schuppanzigh is a scoundrel Who doesn’t know him, the fat sour-belly the conceited ass’s head? Oh scoundrel Schuppanzigh Oh donkey Schuppanzigh We all agree that you are the biggest ass Oh ass, hahaha |

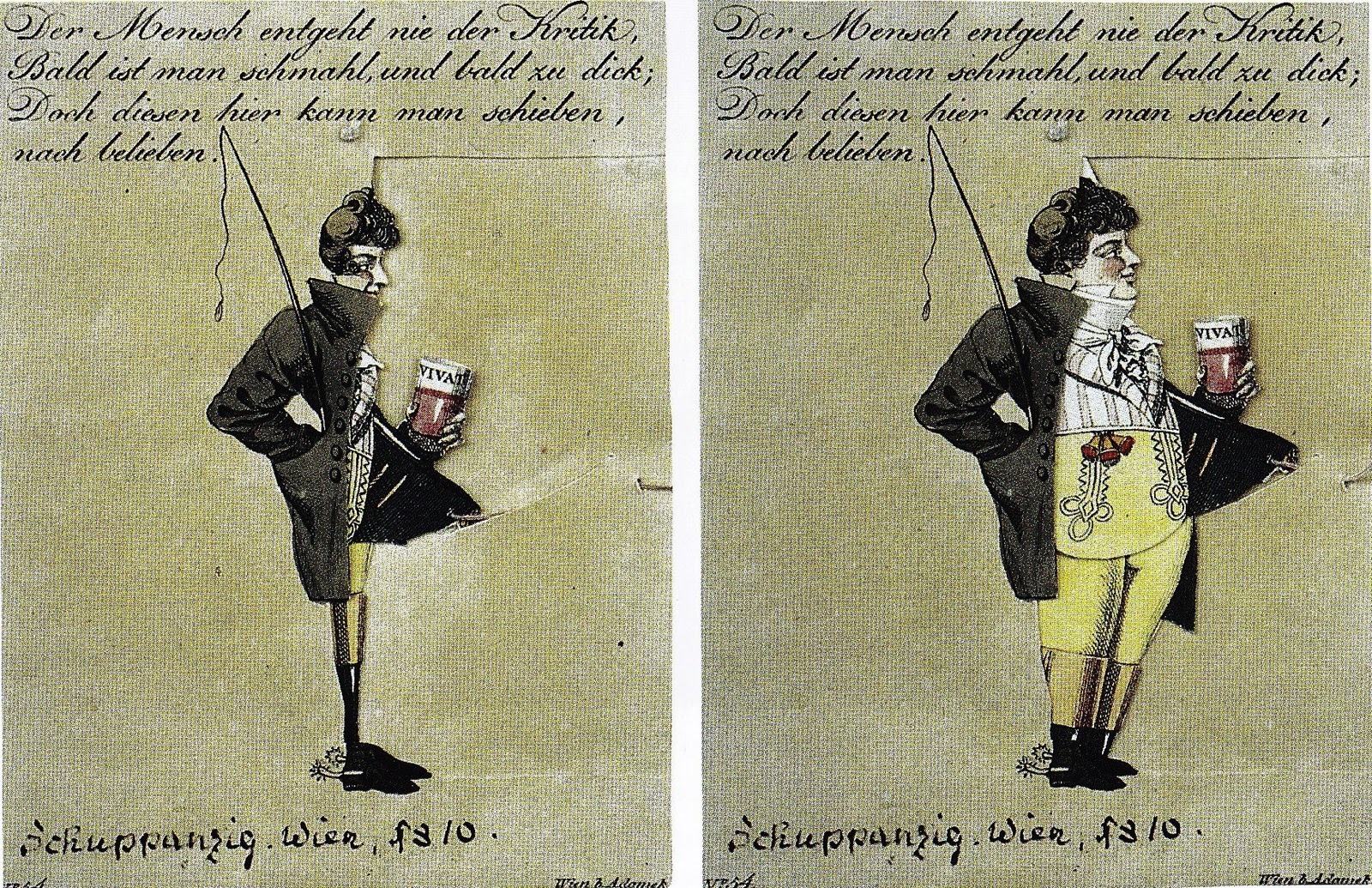

Not a very charming text, indeed! Schuppanzigh’s rotund proportions also made it into popular culture, as a Viennese publisher issued a cardboard caricature with a sliding mechanism. By adjusting the insert, Schuppanzigh would alternately loose or gain weight. Now, I believe, you understand the true hazards of being a teacher! More than 200 years later, thanks to his student Beethoven, we still talk about Schuppanzigh’s weight problem!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter