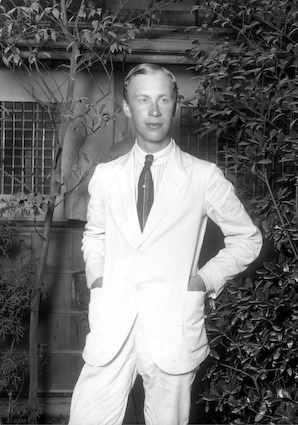

Prokofiev

The piece is modern, prickly, and ranges from one end of the piano to the other. It starts with brisk repetitive notes that spread and come back together, always with a driving urge behind them. New notes, dissonant and pointed, are played against the driving beat, urging us ever onward. Urgent, percussive, unrelenting in its intensity, the work was like no toccata heard before. It’s one of the few pieces where Faster is Better and it’s recorded that no one could do it faster or better than Vladimir Horowitz. After Horowitz, however, we have to recognize Martha Argerich’s phenomenal recording, made in 1960. She did the work in a blistering 4:05, a time rarely equaled, and through the work maintains an intensity that shows how much the simple toccata was changed by Prokofiev’s composition.

Prokofiev – Toccata Op.11 (Martha Argerich)

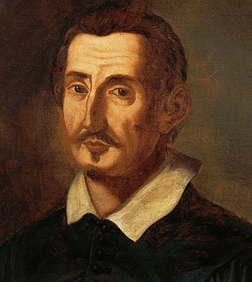

Girolamo Frescobaldi

Frescobaldi: Toccata in C Major (Chigi manuscript)

It was with J.S. Bach that the Toccata as we generally recognize it came into being. His toccatas sound as though they are improvised by the performers and were often followed by an extended fugue movement. One of the most famous examples of Bach’s toccata and fugue combinations is the Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565

Hans-André Stamm on the Trost-Organ of the Stadtkirche in Waltershausen, Germany

After Bach, we have Schumann’s Toccata in C Major, Op. 7, which was published in 1834. It was an important item in the virtuoso repertoire of the young Clara Wieck and her performance of it impressed Mendelssohn. Liszt also wrote a Toccata, dated around 1879, which is toccata-like in its speed but which it otherwise like much of Liszt’s late pieces. In the 20th century, composers such as Ravel, Sorabji, and Rutter have written toccatas, but it is this youthful piece by Prokofiev that still claims our attention, driving and insistent.