Jorja Fleezanis

It’s always fun to hear how someone finds his or her calling. How did you begin your journey?

I was a late bloomer. I had extremely good training in orchestral and ensemble playing at Interlochen, MI. while I was in high school, but when the Cleveland Institute accepted me, I realized that I had to grow up as a violinist in a big way. It took five years of hard work before I thought I could tackle the Brahms Violin Concerto. In my last year, somehow I won the school’s concerto competition performing the Brahms Concerto with orchestra. It was at that point, at age twenty-two, that I thought I could be a professional violinist.

Very soon afterward you won a position in the Chicago Symphony.

I had bombed an audition for the Los Angeles Symphony and then tried out for the Chicago Symphony. I made the finals but they didn’t hire anybody. Fortunately, the committee was willing to share with me what I didn’t do well. I went back for another audition and miraculously I was offered the job. Little did I know that of the five women in the CSO, I was the only single woman, and the youngest at twenty- three years old! I felt quite isolated. I sat at the back but I felt my eyes constantly gazing longingly toward the front stands of the orchestra.

So you resigned?

Yes after only one season. My parents were simply incredulous. I knew I needed much more polish to reach my goal to sit up front.

How did you go about gaining that extra skill and panache?

I went back to Cincinnati where I had been in school before going to Chicago. My boyfriend and I had founded a chamber orchestra. I returned to that, as concertmaster, and I became a founding member of the string trio Trio D’Accordo. Meanwhile, I taught violin and played substitute in the Cincinnati Symphony, so I was heavily involved in the “nitty gritty” of being a freelance musician. I regard these four years as my “polishing years” finally feeling ready to audition for a leadership position.

I went back to Cincinnati where I had been in school before going to Chicago. My boyfriend and I had founded a chamber orchestra. I returned to that, as concertmaster, and I became a founding member of the string trio Trio D’Accordo. Meanwhile, I taught violin and played substitute in the Cincinnati Symphony, so I was heavily involved in the “nitty gritty” of being a freelance musician. I regard these four years as my “polishing years” finally feeling ready to audition for a leadership position.Your San Francisco Symphony audition is a great story. Tell us about it!

I saw a notice for a one-year position as associate concertmaster. When I went to the hall and was assigned a room to warm up, I started hearing all kinds of repertory around me—the solos from Scheherazade, by Rimsky Korsakov and the treacherous solos from Ein Heldenleben of Strauss. I went to the personnel manager and showed him the audition list that I had prepared. To my horror he said, “That’s the list for a first violin position, not the associate concertmaster spot!” I was so flustered that I was speechless. He told me he would speak with the Maestro and see what they could do.

When the personnel manager returned, he asked me if I could play the violin solo in the Brahms First Symphony. I said I thought I could. Then he asked me if I could play the solos in Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du Soldat, which I knew well, having played it many times in my chamber orchestra. I said yes I could, on the fly. So with all the confidence that I could muster, I marched onto the stage of the Opera House. I had never been on such an enormous stage to perform all alone. I thought I didn’t have a prayer of getting the job so I started telling myself, “Play what you love and don’t think about anything else.”

A young man came onto the stage to conduct me in some of the excerpts. I really appreciated that help. Thinking he must be the assistant conductor, between excerpts I confessed to him how dumb I had been not to be prepared. (He kept telling me to forget about it!) Afterwards, the personnel manager told me that Maestro Edo de Waart wanted to see me in his office. I was sure I was going to be yelled at.

When I got to the studio the only person I saw was that nice young man who had conducted me. Then the light bulb went on. All the things I had said to this unknown young man turned out to be the first stepping-stones in my relationship with Edo De Waart, who would be incredibly important to my career.

Edo indicated that he had already found someone for the associate position but he was suitably impressed to offer me the assistant principal second violin position. I had given myself very bad marks but I still must have delivered, which made an impression. I told him that I’d have to think about his offer. Honestly, I don’t know what I was thinking. I didn’t have a job! But I did have a strong zeal for my goal. I let two weeks go by until finally he called me. Unheard of. So I took the job.

A great lesson for young people—to have lofty goals and go for it! So then how did you succeed in getting the associate concertmaster position?

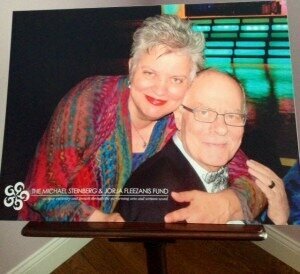

First, it was so obvious to me that this was the orchestra that I wanted to play in. By that time I had met the man I would marry, Michael Steinberg. (JH: the eminent musicologist) He encouraged me to audition. “You know how to work hard. Do it!” he said. The moment they announced that I had won the job was one of the most important moments in my life next to marrying Michael. It led to my association with the composer John Adams, to the Fog Trio with pianist Garrick Ohlssohn and cellist Michael Grebanier and to my future position with the Minnesota Orchestra. One never knows about those unexpected threads that weave your entire life.

First, it was so obvious to me that this was the orchestra that I wanted to play in. By that time I had met the man I would marry, Michael Steinberg. (JH: the eminent musicologist) He encouraged me to audition. “You know how to work hard. Do it!” he said. The moment they announced that I had won the job was one of the most important moments in my life next to marrying Michael. It led to my association with the composer John Adams, to the Fog Trio with pianist Garrick Ohlssohn and cellist Michael Grebanier and to my future position with the Minnesota Orchestra. One never knows about those unexpected threads that weave your entire life.Tell us how you were the one to play the premier of the Violin Concerto by John Adams in 1994.

Edo de Waart had been a champion of John Adams at a time when John was poised to “become something.” So it was possible to get a piece from him. A consortium of groups commissioned him including the Minnesota Orchestra, the London Philharmonic and the New York City Ballet. Gidon Kremer played the European premier of the piece. John believed in honoring those who had believed in him, so although I was not a “soloist” I was the lucky one. I couldn’t believe that I was actually having exchanges with the composer about what he might write. I was so enamored of his music. John was thankful for our interactions. It was like a child being born. He sent completed music page by page via fax. I remember saying to myself, “I’m going to have the privilege of putting the first imprint on this music. There are limitless possibilities where there are no previous tracks, while the ink is not yet dry!” The slow movement is a profound Chaconne with deep connotations inspired by the poem Body through which the dream flows by poet Robert Hass.

Jorja and Janet

Aaron wrote The Sky My Husband, for Piano, Percussion, baritone and violin, which was commissioned by the Schubert Club of Minnesota for my New York recital in 1990.

We all are asked from time to time who our favorite composers are. Do you have a favorite?

I’m a romantic. I love Brahms. I am also a big fan of Igor Stravinsky, especially his impeccable rhythmic discipline and fantastical imagination. I love the mixed meters in Béla Bartók’s music too, which is akin to Greek dance. As an ethnic person I totally identify with the folk music vernacular in Bartók’s music.

There is a story I wish you’d relate. Carnegie Hall with Leonidas Kavakos performing the Sibelius Violin Concerto.

Kavakos is someone who appears to never be fazed. At this performance though, he was uncharacteristically distracted. He kept examining his violin. He really seemed distressed. I was in my own world, as this was my last concert with the Minnesota Orchestra at Carnegie Hall. Finally, before the last movement, he whispered to Osmo Vänskä our conductor. Vänskä told Kavakos to play on, but after the first phrase Kavakos handed his violin to me as well as his chin rest, which had come off the violin. It’s not something you can do much about! I handed him my violin. I knew that I’d need some kind of tool to screw the chin rest back on…but what? I remembered that I was wearing pearl studs, which seemed to fit right into the hole. But the chin rest fell off again. It turned out that the cork underneath was flattened down to the thickness of phyllo dough. I had no choice but to play without a chin rest. But Kavakos! He played all the acrobatic feats of the last movement of the Sibelius on an unfamiliar instrument and was not flustered. He made it happen. We on stage were all aghast at his brilliance. His encore was Paganini— pyrotechnical, full of octaves and 10ths. The moral of the story is that anything can happen. You must be malleable. It was poetic for me. It was the first time I heard someone play my violin and of course he’s a Greek too.

John Adams Violin Concerto Chaconne:

FOG Trio with Garrick Ohlsson, Jorja Fleezanis and Michael Grebanier

Brahms Piano Quartet in C minor:

Thank you for this inspiring interview! I love hearing the stories of bold, talented women who blaze the trail for the rest of us. Jorja’s amazing performances reflect her amazing life.