Richard Strauss and

Hugo von Hofmannsthal

Credit: http://www.dw.de/

In Greek mythology, Elektra is widely considered the most psychologically advanced Greek tragedy. The Greek dramatist Sophocles constructed a play that centers on the heroine’s obsession to avenge her father’s murder. Elektra lives in hope that her brother Orest would eventually return to slay their murdering mother and her lover. This timeless story of pathological hatred, self-perpetuating violence and sexual aberration came to the attention of the Viennese poet and dramatist Hugo von Hofmannsthal in 1901. But it was a specific request from the brilliant theater director Max Reinhardt in the summer of 1903 that prompted Hofmannsthal to fashion a version that ingeniously combined naturalistic theater with the psychological trappings of symbolist poetry. By focusing on the uncontrollable psyches and irrational obsession of the characters, and anticipating groundbreaking developments in psychiatry, Hofmannsthal brought Elektra into the 20th century. Cultural historians have suggested, “Myth becomes the embodiment of psychological extremism as Hofmannsthal collides with his contemporary Sigmund Freud.”

Hofmannsthal’s play was first staged, under the direction of Max Reinhardt, at the “Kleines Theater in Berlin” on 30 October 1903. During its initial run, it received ninety performances and was revived in 1905, 1908, and 1909. Richard Strauss, who was working as a conductor at the Berlin Court Opera, saw Elektra during the 1905 revival and immediately recognized its potential as an opera subject. He was principally “riveted by its use of gesture, the concentration of action and the steadily rising tension towards Electra’s dance after his father’s murder has been avenged.” Collaboration began in earnest in June 1906, and Strauss was keen to “set this demonic, ecstatic Greek mythology of the sixth century against Goethe’s humanity.” Yet, when Strauss, one of the most fluent and confident musicians of his time, started work on the musical score, he began to suffer from composer’s block. Strauss had always had a somewhat ambivalent attitude toward his parents. His domineering, abrasive and mildly abusive father Franz had died in 1905. His death plunged Strauss’s mother into a massive nervous breakdown that necessitated permanent confinement in a sanatorium. Apparently, the Elektra text had triggered deep anxieties, as it took Strauss more than two years to finish the score. The noted Strauss scholar Bryan Gilliam suggests, “Every measure of the music contains a torrential savagery of sensations that plunges the listener into a world of naked and uncontrollable emotions.”

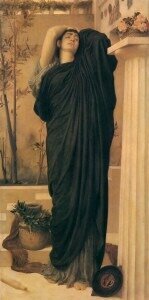

Elektra

Credit: Wikipedia

The complex emotions surrounding Elektra and her relationship to her dead father, her mother, sister and brother, and indeed the entire interactions of this supremely dysfunctional family as described in the ancient myths have been retold countless times throughout history, and offered a wonderful psychological potential to be explored. Sigmund Freud referred to a girl’s psychosexual competition with her mother for possession of her father as a “feminine Oedipus attitude,” but it was Carl Gustav Jung—the founder of analytical psychology—who first defined what he called the “Elektra Complex” in 1913. We can’t be sure whether Jung’s clinical breakthroughs were directly inspired by the dramatic and musical reflections of Hofmannsthal and Strauss, but they certainly contributed to an open discourse on the subject. In that sense, as scholars have rightfully suggested, “Elektra is Strauss’s most successful opera, although clearly not his most popular.”