Raphael: The Marriage of the Virgin (Lo Sposalizio)

We’ll look at an important book in the history of the English madrigal, a tour of Italy taken by a famous pianist, and the inspiration from Florence in this overview of the Italian influence.

In 1588, there appeared in England a collection entitled Musica Transalpina (Music from Across the Alps). Published in London by Nicholas Yonge, Musica Transalpina can be said to be the true start of the English madrigal school. It took Italian madrigals by 18 different composers, with the majority by Alfonso Ferabosco and Luca Marenzio, and gave them English words, thereby bringing them into the understanding of the local performers. Ferrabosco was a familiar name to the English, as he had been at the court of Queen Elizabeth I from 1562 to 1578.

Marenzio: Tirsi morir volea (Concerto Vocale, René Jacobs, cond.)

The highly suggestive madrigal Tirsi mirir volea, was ‘Englished’ into Thirsis to die desired and so entered the general English musical scene.

Musica Transalpina, 1588

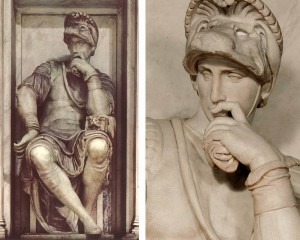

Liszt: Années de pèlerinage, deuxième année, Italie, II. Il penseroso (Jenő Jandó, piano)

Although Tchaikovsky entitled his String Sextet in D minor as “Souvenir de Florence,” it’s actually a curious mix of a light Italian beginning with a strong Russian ending. The composer, according to his brother Modest, created the first theme of the work in Florence, hence the title. We hear so many of the musical materials as reflecting the Russian imagination of Italy with its passion, beguiling flirtations, and, above all, its songfulness. When we look at the first movement, it captures so many of those elements.

Tchaikovsky: Souvenir de Florence, Op. 70: I. Allegro con spririto (Vienna String Sextet)

Compare that beginning with the start of the final movement, where we are clearly in the folk music of Russia and no longer in the sunny south.

Michelangelo: Il penseroso

For Nicolas Yonge and his Musica Transalpina, Italy was the source that had to be translated for the local market. Once the Italian madrigal became the English madrigal, it was something that the English could move forward and make into their own creation. For the Romantic side of Liszt, he saw the arts of Italy as an inspiration for some of his most important piano music. For Tchaikovsky, Italy was also an inspiration, but in a different way than Liszt found it. This isn’t the end of the Italian influence story, but merely a glimpse into the different ways Italy affected those who looked to her for inspiration.