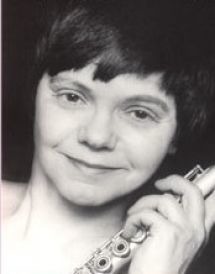

When Doriot Anthony Dwyer, flutist was selected as one of the first woman principal players in a top five U.S. orchestra the press went crazy, “Woman Crashes Boston Symphony: Eyebrows Lifted as Miss Anthony sat at Famous Flutist’s Desk,” “Flutist, 30 and Pretty, Here with Boston Symphony.” (Boston Globe, 10/12/1952) She had broken not a glass ceiling but a concrete one!

When Doriot Anthony Dwyer, flutist was selected as one of the first woman principal players in a top five U.S. orchestra the press went crazy, “Woman Crashes Boston Symphony: Eyebrows Lifted as Miss Anthony sat at Famous Flutist’s Desk,” “Flutist, 30 and Pretty, Here with Boston Symphony.” (Boston Globe, 10/12/1952) She had broken not a glass ceiling but a concrete one!

Today, most orchestras in the world have plenty of women artists on virtually every instrument. The Berlin and Vienna Philharmonic’s track records have been abysmal, although it is getting better in Berlin, where of 125 members 25 are women. Vienna currently has seven women players. Women were demeaned as performers in the symphonic world in the 1950s and 1960s.

In 1923, three years after women were granted the right to vote, Alfred Hertz conductor of the San Francisco Symphony hired the first woman player in the country, yet in the 1970’s women accounted for less than 5 percent of the musicians in the top five orchestras. In fact Zubin Mehta, who was the music director of the Los Angeles Symphony at that time, said, “I just don’t think women should be in an orchestra. They become men.” (New York Times)

The only woman in the Boston Symphony in 1952 was a harp player, which was deemed a “feminine” instrument. There were no facilities for women. In fact, even when I joined the Minnesota Orchestra in the 1980’s— the only female principal string player—we women often had to change behind a curtain hung up for the occasion. Generously, the BSO harpist who used her harp case as a dressing room, offered to share. Dwyer demurred. After such a grueling journey to get to her goal she insisted on a space to call her own. A converted green room became her dressing room.

The only woman in the Boston Symphony in 1952 was a harp player, which was deemed a “feminine” instrument. There were no facilities for women. In fact, even when I joined the Minnesota Orchestra in the 1980’s— the only female principal string player—we women often had to change behind a curtain hung up for the occasion. Generously, the BSO harpist who used her harp case as a dressing room, offered to share. Dwyer demurred. After such a grueling journey to get to her goal she insisted on a space to call her own. A converted green room became her dressing room.

Doriot was born in Illinois in 1922 to a musical family. Her mother was an accomplished flute player and her father, William C. Anthony, (related to but disapproving of his cousin, suffragette Susan B. Anthony) played the bass. Doriot was dying to play the flute but her family didn’t allow it until she was eight years old. She studied with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s principal flute, and soon won a national solo competition, which allowed her to attend the Interlochen Center for the Arts where she was awarded a scholarship to the Eastman School of Music.

Dwyer didn’t escape gender bias there or when she auditioned for the Pittsburgh Symphony. The conductor, although he was impressed with her playing said, “You don’t want to play in Pittsburgh. They’re all men!” She did win second chair flute of the National Symphony in 1943 performing there for two years.

New York City was her next stop. At the ripe old age of 23 she performed jazz and played with the Ballet Russe. In 1945 she moved to the west coast after again landing second chair, this time with the Los Angeles Symphony. Dwyer said of her time there, “I considered those years in Los Angeles my ‘college’.”

When the Boston Symphony Orchestra announced the retirement of its principal flutist, Georges Laurent in 1952, Dwyer hurried to apply, making certain to specify that she was “Miss” Doriot Anthony. She included two letters— recommendations from violinist Isaac Stern and from the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s Maestro, Bruno Walter.

When the Boston Symphony Orchestra announced the retirement of its principal flutist, Georges Laurent in 1952, Dwyer hurried to apply, making certain to specify that she was “Miss” Doriot Anthony. She included two letters— recommendations from violinist Isaac Stern and from the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s Maestro, Bruno Walter.

Auditions are grueling under any circumstance. Candidates will play over and over until numbers are reduced to a select few. Often the conductor might veto the candidates chosen by a committee. In the “old” days the Maestro made the decisions. Charles Munch couldn’t care less about the flutists he had heard. A “Ladies Day” was scheduled. After arduous non-stop playing it was narrowed down to two women. Then one was dismissed. Dwyer seemed victorious. Munch asked her to come back for a second audition. He was not ready to give in so easily. She was nonplussed—What? More punishment? Allow the management to solicit other candidates perhaps from the International community, a male player presumably? She held her ground and said no, she would not re-audition.

Two months of agonized waiting followed while the BSO deliberated. Then the announcement was made. Musicians were impressed, as they knew that it was unusual if not unprecedented that a second player was promoted to a principal position.

Dwyer began immediately. In a concert dubbed “Ladies’ Day” October 18,1952 the review stated, “(she) handled her part in the Bach’s charming Suite deftly and musically and …with a degree of virtuosity that elicited from her fellow-players something midway between a gasp of astonishment and a shout of approval, while the audience expressed its appreciation in no uncertain terms.” (Warren Storey, Boston Globe.)

Zwilich flute concerto with Dwyer

As principal flute for 38 years, Dwyer performed with the greatest maestros including Munch, Erich Leinsdorf, Seiji Ozawa, Georg Solti, Pierre Boulez and many others garnering many awards during her almost four decades with the orchestra.

At age 67 in 1989 Dwyer announced her retirement. The BSO honored her by commissioning Ellen Taaffe Zwilich to write a flute concerto dedicated to her. After the premiere the Boston Globe named Dwyer the living legend of flute playing.

Listen to the famous flute melodies from Debussy’s Prélude à L’après-midi d’un Faune and you’ll agree and note if you see any other women!

Debussy Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune Bernstein conducts BSO

Please correct the date of Boston Globe Article in paragraph one. It could not hard been 1925. You must mean 1952.

Many thanks! We have corrected the typo error.

With all due respect, if you mean the top 5 U.S. orchestras to mean the “Big Five’ of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, & Cleveland, then Helen Kotas was actually the first woman principal. She was principal Horn for Chicago from 1941-1947.

Also, some spelling errors: “Erich” not Erick Leinsdorf and “Georg” not George Solti.

Many thanks for spotting the errors, they have been corrected.