Credit: http://banteerns.ie/

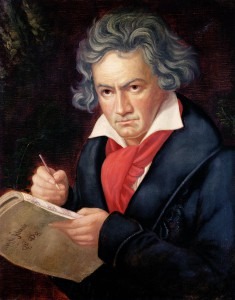

When we think of FIVE in relation to music, all sorts of things come to mind: our five fingers at the piano, the five Russian composers known as The Mighty Handful, and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, just for starters.

Taking Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 as being indicative of his first great symphony, it’s interesting to see that there are other composers for whom their Symphony No. 5 was also their great symphony. We can look at, for instance, Tchaikovsky. His Symphony No. 5, although part of a larger trilogy of symphonies focused on the idea of “destiny,” stands alone. The final movement begins with the themes from the first movement but quickly escalates it into grand gestures.

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5: IV. Finale: Andante maestoso – Allegro vivace (Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Claudio Abbado, cond.)

Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5 is another great work in the hands of a master. Written in Russia while the Germans were advancing towards Moscow, It was the first work by Prokofiev after his return from the west. Its tremendous final movement, which begins with a slow recollection of the first movement, quickly launches into its allegro with all of the emotion and rhythm for which Prokofiev was so well known.

Prokofiev: Symphony No. 5: IV. Allegro giocoso (City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; Simon Rattle, cond.)

Shostakovich Symphony No. 5, written in 1937, was such a success at its première that the ovation at the end lasted well over half an hour. The last movement, again, is the movement that carries the real emotion of the symphony. Its fortissimo opening, with trumpets and pounding timpani, sweeps up the listener and carries him into a heroic future.

Shostakovich Symphony No. 5: IV. Allegro non troppo. (London Symphony Orchestra; André Previn, cond.)

And now back to Beethoven. Although the final movement has the heroic stature we’ve seen elsewhere, we always seem to listen to the first movement with the most concentration. Those opening notes push us forward and with Roger Norrington’s particularly quick tempo, we can start to hear this as something more than a symbol.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 5: I. Allegro con brio (London Classical Players; Roger Norrington, cond.)

What’s interesting is that this focus on the fifth really only works with composers with a relatively small symphonic output. Mozart’s Symphony No. 5, which was written when he was only 9, is a light piece of fluff.

Mozart: Symphony No. 5: I. Allegro (Concentus Musicus Wien; Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cond.)

Haydn’s Symphony No. 5, written just 5 years before Mozart’s, is known for its high horn parts but otherwise doesn’t approach the level that he attained in his final symphonies.

Haydn: Symphony No. 5: I. Adagio, ma non troppo (Vienna State Opera Orchestra; Max Goberman, cond.)

Pity, then poor Brahms and poor Schumann, who each only wrote 4 symphonies Even though they were in a position to write significant Fifths, they never did.