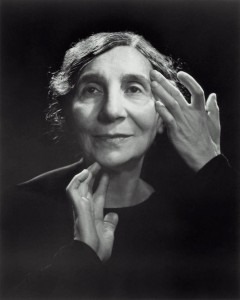

Wanda Landowska © 31.media.tumblr.com

Virtuoso, musicologist, distinguished author, a woman who was, “in love with her audience,” Wanda Landowska’s dynamic and powerful playing single-handedly revived interest in the harpsichord. Her performance of J.S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations at New York’s Town Hall, in 1942 was the first time in the modern age the piece was played on the harpsichord—the instrument for which the work was written. No background tinkling for her—she performed on massive heavily built harpsichords—some with two and even three keyboards. The sound is astonishing.

J.S. Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 (Wanda Landowska, harpsichord)

Landowska was born in Warsaw, Poland in 1879, to a cultured family. Landowska was only four years old when she began her music lessons and by age eight had already revealed her predilection—not for the romantic masters, which dominated music at the time—but for the music of Bach and other seventeenth and eighteenth century composers. At seventeen Landowska was off to Berlin to complete her studies with stern instructors who specialized in the music of Chopin. The music of the past was fairly unknown and oftentimes maligned, leaving Landowska, “full of longing for my old-time music…my music book was covered with exercises in which I had no interest at all.”

New ideas and a spirit of rebellion against romanticism were forming in France. It didn’t hurt that Landowska had met Henry Lew, an eminent ethnologist in Berlin. In 1900 they eloped to Paris. Deeply interested in research especially of the works of J.S. Bach, François Couperin and Jean-Philippe Rameau. Wherever she performed, Landowska took time to visit the museums of Europe to study manuscripts and to seek out the first keyboard instruments.

© www.thinglink.com/

Among the instruments she encountered was a harpsichord with three keyboards, gorgeous painting on the lid, and with a depth of sonority she had not encountered before. She promptly fell in love and for the first time envisioned the interpretive possibilities of the instrument. Landowska elicited the help of the lead engineer of the piano firm Pleyel to recreate an instrument for her that had, “the resounding voice of harpsichords used by Bach and Handel.” Together they took notes and measurements of all the instruments in Brussels, in Leipzig, in England, discovering that no harpsichords were alike. Landowska asked the engineer to build an instrument that combined the best features of historic harpsichords— while extending their capabilities to be able to perform contemporary music as well as traditional literature.

Her dream came true in 1912 with the delivery of a two-keyboard instrument outfitted with a deep register, called a 16-foot, sounding one octave below normal pitch, as a counterpart to the 4-foot register, which is tuned an octave above normal pitch and two 8-foot registers and a lute-stop.

Landowska began writing articles, which appeared in important literary publications in defense of her ideas on interpretation. Landowska believed that the performer should “add her own style, combining intuition and knowledge to produce an ‘ecstasy of music’.”

In 1909 her meticulously researched book Musique Ancienne caused quite a stir among her detractors. The public had very little if any exposure to this music let alone the relic, the harpsichord. Germany was one country that favored the rebirth of the instrument. The director of the Hochschule für Musik invited Landowska to Berlin to teach a harpsichord class in 1913. At the outbreak of World War I, as a “foreigner”—a naturalized French citizen of Polish descent, Landowska and her husband became civilian prisoners. She could teach but her writings would no longer be published. After the end of the war, when Landowska and her husband prepared to return to France, Lew was killed in an accident.

Landowska forged ahead and devoted herself to rebuilding her career. At the invitation of Leopold Stokowski she toured the United States in the 1920’s, performing on both the piano and harpsichord. She was featured in Manuel de Falla‘s El Retablo de Maese Pedro (Master Peter’s Puppet Show) —notable in that it marked the return of the harpsichord to the modern orchestra, and in works written for her including de Falla’s Concerto for Harpsichord.

Poulenc: Concert Champêtre for Harpsichord and Orchestra

Francis Poulenc was in the audience for the premiere of de Falla’s Retablo. He said, “I was fascinated by the work and by Wanda. ‘Write a concerto for me’ she said. I promised her to try. My encounter with Landowska was a capital event in my career… Wanda is an interpreter of genius. The way in which she has resuscitated and recreated the harpsichord is a sort of miracle.” He wrote his Concert Champêtre (Pastoral Concerto) for her.

Wanda Landowska Harpsichord Home Movie 1927

Wanda Landowska established the École de Musique Ancienne in Paris in 1925 and in 1927, as her life-long companion Denise Restout relates, Wanda decided to build a small concert hall in the back of the garden of her home in Saint-Leu-la-Forêt, which could seat 300 people and would became a center for the performance and study of old music. She gave 12 concerts every summer followed by 12 public master classes. “Students came from all over the world—not only harpsichordists and pianists, musicologists and all types of musicians as well as writers…”

Landowska had amassed a valuable collection of manuscripts, instruments, paintings, and photos. Saint-Leu-la-Forêt was the ideal place for her extensive library, two modern pianos, two Pleyel harpsichords, and priceless antique instruments— clavichords, spinets, a 1642 Ruckers harpsichord, pianofortes, a small organ dated 1737, as well as original manuscripts of Karl Philipp Emanuel Bach’s keyboard concertos.

At the dawn of WWII, Landowska who was of Jewish origin, was urged to flee. She and Restout escaped to the south. When they heard that the Nazis had looted Landowska’s home they embarked for Lisbon and then the United States. They had no idea that their flight from France would be forever. Fortunately, Restout had the foresight to throw Landowska’s writings into the few suitcases they could carry. Restout became the editor and translator of Musique ancienne, and Landowska on Music.

Shortly after her arrival in the U.S. Landowska played the 1942 recital of Bach’s Goldberg Variations and also appeared as piano soloist in performances of Mozart. According to critic and composer Virgil Thomson, “Wanda Landowska’s playing of the harpsichord at Town Hall last night reminded one… that there does not exist in the world today, nor has there existed in my lifetime, another soloist of this or of any instrument whose work is so dependable, so authoritative and so thoroughly satisfactory. From all the points of view- historical knowledge, style, taste, understanding and spontaneous musicality- her renderings of harpsichord repertoire are, for our epoch, definitive.

J.S. Bach: The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1, BWV 846-869 (Wanda Landowska, harpsichord)

Landowska settled in Lakeville, Connecticut in 1949 and continued to tour extensively, teach, and record, among other works, Johann Sebastian Bach’s entire Well Tempered Clavier, Book 1 and Book 2—over 5 hours of music—which we are fortunate enough to be able to hear today.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter