Traditional commedia dell’arte Pulcinella

On 15 May 1920, the new ballet Pulcinella opened at the Paris Opéra. The story and the choreography were by the dancer Léonide Massine, the music was by Stravinsky, and the costumes and sets were by Picasso.

It was this kind of collaboration that made the Ballets Russes still be remembered today. The character Pulcinella comes from the 16th century Italian commedia dell’arte stories. Pulcinella was a stock character who always dressed in white, wore a black mask, had a round belly, and was best known for his long-beaklike nose, which is where his name, meaning little chick, derives.

Léonide Massine as Pulcinella in the 1920 production of Pulcinella

Set design for Pulcinella

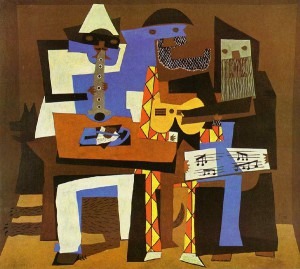

In Picasso’s Three Musicians, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, we have Pulcinella on clarinet, Harlequin and a monk, all familiar characters from the commedia dell’arte.

This cubist work draws on the same characters he’d already been working on for the Pulchinella ballet.

Picasso: Three Musicians (1921)

Stravinsky: Pucinella Suite: I. Overture (New York Philharmonic; Pierre Boulez, cond.)

From the beginning of the Overture, we know that although the melodic ideas might be from the 18th century, the sound is certainly modern.

Stravinsky: Pucinella Suite: IV. Tarantella (New York Philharmonic; Pierre Boulez, cond.)

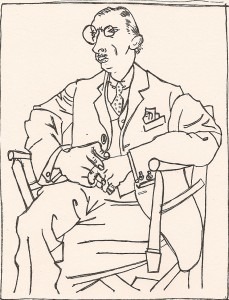

Stravinsky by Picasso

Stravinsky: Pucinella Suite: VIII. Finale (New York Philharmonic ; Pierre Boulez, cond.)

It all comes together in the Finale: the brisk bright rhythms, the repetition of small themes, the little motifs that get tossed between instruments – we’re far from the extended melodies of Pergolesi and very much in the 20th century.

It was Diaghilev who brought Picasso and Stravinsky together – the Russian and the Spaniard probably would have never worked together otherwise – and through their work together on Pulcinella, we are left with three iconic musicians.