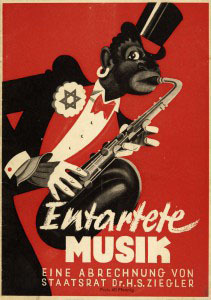

The Reichsmusiktage (Music Days of the 3rd Reich) in 1938 featured a number of customary performances and lectures. However, it also marked the opening of an exhibit entitled Entartete Music (Degenerate music). The exhibit was intended to show the “cultural degradation and moral threat posed to the nation by Jewish and other degenerate musicians.” Although difficult to define, the main criteria for inclusion in the exhibition were race and modernism. The advertisement for the exhibit showed a black jazz musician with the features of an ape, playing a saxophone and wearing a Jewish star. The source of this image was neither Jewish nor was it black. Rather, it came from the enormously popular opera Jonny spielt auf (Jonny Plays) by the Catholic Austrian composer Ernst Krenek. Typifying the cultural freedom and decadence of the golden era of the Weimar Republic, the opera premiered in Leipzig and was given 421 times on various stages in its first season alone.

The Reichsmusiktage (Music Days of the 3rd Reich) in 1938 featured a number of customary performances and lectures. However, it also marked the opening of an exhibit entitled Entartete Music (Degenerate music). The exhibit was intended to show the “cultural degradation and moral threat posed to the nation by Jewish and other degenerate musicians.” Although difficult to define, the main criteria for inclusion in the exhibition were race and modernism. The advertisement for the exhibit showed a black jazz musician with the features of an ape, playing a saxophone and wearing a Jewish star. The source of this image was neither Jewish nor was it black. Rather, it came from the enormously popular opera Jonny spielt auf (Jonny Plays) by the Catholic Austrian composer Ernst Krenek. Typifying the cultural freedom and decadence of the golden era of the Weimar Republic, the opera premiered in Leipzig and was given 421 times on various stages in its first season alone.

Ernst Krenek: Jonny spielt auf (Jonny Plays), excerpts

The plot hinges on a valuable violin that changes hands several times in the course of the opera. Whether by theft or misplacement it eventually passes, from a European concert virtuoso to a black-American dance-band musician. The opera freely combines the sounds of Jazz with aspects of neo-romanticism and musical modernism, making it a symbol of the artistic freedom prevalent in the 1920’s. With the rise to power of the Nazi party in 1933, however, this cultural pluralism came to an abrupt end. Krenek had started his musical career in Vienna, composing his first pieces at age 6. He enrolled in the Vienna Academy of Music to study with Franz Schreker, and followed his teacher to Berlin in 1920. In the company of Ferrucio Busoni, Hermann Scherchen and Artur Schnabel he completed his first violin sonata, a hyper-romantic and over-refined work that openly takes its inspiration from his teacher Schreker and from Max Reger.

Ernst Krenek: Violin Sonata in F-sharp minor, Op. 3

Krenek first met Stravinsky in November of 1924 and sat through the premier performance of Stravinsky’s recently completed Piano Concerto, with the composer at the piano. It made on him, an “almost terrifying, astonishing, and elementary impression,” which was reinforced by his conversations with Stravinsky after the performance. In Paris, he also met Milhaud and Honegger, and the impression of France “caused a complete about-face in my artistic outlook. I was fascinated by what appeared to me the happy equilibrium, perfect poise, grace, elegance, and clarity, which I thought I perceived in French music of that period. I decided that the tenets I had followed so far in writing ‘modern’ music were totally wrong. Music, according to my new philosophy, had to fit the well-defined demands of the community for which it was written; it had to be useful, entertaining, practical.”

Krenek first met Stravinsky in November of 1924 and sat through the premier performance of Stravinsky’s recently completed Piano Concerto, with the composer at the piano. It made on him, an “almost terrifying, astonishing, and elementary impression,” which was reinforced by his conversations with Stravinsky after the performance. In Paris, he also met Milhaud and Honegger, and the impression of France “caused a complete about-face in my artistic outlook. I was fascinated by what appeared to me the happy equilibrium, perfect poise, grace, elegance, and clarity, which I thought I perceived in French music of that period. I decided that the tenets I had followed so far in writing ‘modern’ music were totally wrong. Music, according to my new philosophy, had to fit the well-defined demands of the community for which it was written; it had to be useful, entertaining, practical.”

Ernst Krenek: Concertino, Op. 27

By the late 1920’s, Krenek turned away from the neoromantic style and turned to Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique. Although he took a different attitude towards dodecaphonic music than Schoenberg, he greatly believed in its uncompromising standards and its possibilities for further development. In one-way or another, the twelve-tone system colored his work for the remainder of his career. During his early days of exile in the United States, he explored the twelve-tone system through a lens of Christian humanism. Scored for a cappella voices, the Lamentatio Jeremiae prophetae fuse twelve-tone principles with modal counterpoint of the Renaissance.

Ernst Krenek: Lamentatio Jeremiae prophetae, Op. 93, II

Having been married to Anna Mahler, his mother-in-law Alma asked Krenek to complete her husband’s Symphony No 10. Krenek edited the first and third movements but did not attempt to complete the sketches for the second and fourth. However, when the pianist Eduard Erdmann asked Krenek to complete Schubert’s “Reliquie piano sonata,” Krenek went ahead and completed the fragmentary third and fourth movements. “Completing the unfinished work of a great master,” Krenek wrote, “is a very delicate task. It can honestly be undertaken only if the original fragment contains all of the main ideas of the unfinished. In such a case a respectful craftsman may attempt, after an absorbing study of the master’s style, to elaborate on those ideas in a way, which to the best of his knowledge might have been the way of the master himself.” Pianists up to this day continue to be divided, with purists performing only the first two original Schubert movements. Without knowing the background, would you be able to tell the difference?

Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata No. 15 in C Major, D. 840, “Reliquie”