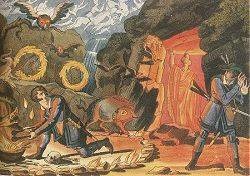

Wolf’s Glen scene

One of his most interesting works is his book, The Elements of the Beautiful in Music, published in London in 1876. In the second chapter, he looks at the affective properties of keys, as did many other 19th century composers. But, unlike them, he actually listed works that he felt fulfilled his requirements.

Last time we looked at C major – let’s move to C minor. According to Pauer, C minor is the key that is expressive of softness, longing, sadness, solemnity, dignified earnestness, and a passionate intensity. It lends itself most effectively to the portraiture of the supernatural. Soft longing.

His examples cover Weber with another scene from Der Freischütz, a song by Shubert, and 3 movements from Beethoven symphonies.

Weber’s opera Der Freischütz (The Marksman) was one of first German Romantic operas and is full of the supernatural: there are enchanted bullets to hit the target in the competition, with the last bullet intended to kill the heroine, we have the ‘Wolf’s Glen’ scene, with its night setting and magical summonings from the dungeon dimension as Casper calls upon the demon Samiel.

Weber: Der Freischütz: Act II: Finale: Milch des Mondes fiel aufs Kraut (Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cond.)

Moving out of the supernatural to a softer side, we have Schubert’s song “Des Mädchens Klage” (The Maiden’s Lament). A young woman sits on the seaside during a storm, the fury of Nature matching her internal torment: her young man has died and with him, her heart.

Schubert: Des Mädchens Klage, D. 191 (Regina Jakobi, mezzo-soprano; Ulrich Eisenlohr, piano)

Beethoven, of course, brings us the first movement of his Fifth Symphony in c minor and the third movement, which Pauer calls the “Funeral March.” The two movements couldn’t be more different yet they both capture the dignified earnestness that Pauer sees as characteristic of the key of C minor.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67: I. Allegro con brio (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Roger Norrington, cond.)

Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67: III. Allegro (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Roger Norrington, cond.)

Although these are the only works that Pauer lists as emulating C minor, we have to note that Beethoven’s own works gave C minor an association with heroic struggle and post-Beethoven composers took this as critical to their own use of the key.

We can add to this list Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 in C minor where he struggled for 20 years to match Beethoven’s achievement in the symphonic form, Saint-Saëns’ Symphony No. 3 in c minor, and Bruckner’s three symphonies (Nos. 1, 2, and 8) in that key. There were dozens of symphonies in C minor written after Beethoven’s No. 5 in 1808 and they must be considered in light of the effect that Beethoven gave to C minor.

Next: G major

Bach’s works seem to be ignored here, but his Passacaglia seems to evoke a struggle against bounds, and finally passionate intensity.