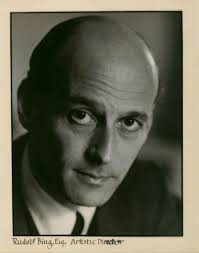

Rudolf Bing

Credit: http://ifthenisnow.eu/

The Austrian born impresario (1902) rose to fame on the back of his two decade reign of the Metropolitan Opera of New York. He gained global recognition beyond the opera world with his two memoirs, the unforgettable classic “5000 Nights at the Opera” and the slightly more forgettable “A Knight at the Opera.” He twice made the cover of Time magazine.

Rudolf Bing with Leontyne Price

and Franco Corelli

Credit: http://parterre.com/

Taking over the Metropolitan Opera in 1950 (after a one year preparatory season in which he just observed), Bing started in an era of grand opera, when everything America did was on a Grand scale indeed. Not content with a full opera season at their Manhattan home, the entire opera company went on a seven week summer tour to the American heartlands. It was a massive exercise involving dozens of train wagons of costumes and equipment and over 300 staff including many disgruntled prima donnas. No wonder Bing likened the tour to the “the biggest thing after Barnum & Bailey, except that giraffes don’t get hoarse.” The Met also had the tradition of decamping the entire company to Philadelphia on selected Tuesday nights.

Rudolf Bing with La Callas

Credit: http://farm4.static.flickr.com/

He developed the still young art of opera telecasts, radio broadcasts and LP recordings (Columbia Records), and didn’t shy away from sprucing up performances, notably operettas, with a little help from the American musical theatre, accepting that the ‘Metropolitan Opera has a Broadway address.’ Indeed, the massive theatre occupied an entire city block on Broadway between 39th and 40th Street.

Chagall at the Met

Credit: http://www.weinerelementary.org/

But the Old Met was a house with tremendous technical and structural challenges, and completely inadequate backstage facilities. The board had decided to move to the newly developed Lincoln Center, and the Old Met had its final curtain in April 1966, with a roll-call of the greatest voices of the time: Giovanni Martinelli, Zinka Milanov, Robert Merrill, Nicolai Gedda, Jon Vickers, Renata Tebaldi and Birgit Nilsson were among the 57 artists chosen.

Glaringly absent was arguably the biggest name of the opera world, Maria Callas. In a much publicised spat, Bing had fired the diva in 1958 for breach of contract after she reneged on her obligations of alternating Lady Macbeth and Violetta in a short period of time. His terse commentary was classic Bing: “Madame Callas is constitutionally unable to fit into any organisation not tailored to her own personality.” Relations remained ice-cold for years, but Callas did make a triumphant return in 1965 in two sold-out performances of Tosca opposite Franco Corelli. But the spat made it clear: this was an era where the impresario dictated the terms, not the singers, no matter how famous they were.

Otello “Già nella notte densa” : Franco Corelli and Tsilis-Gara

Rudolf Bing shepherded the entire company to the new, custom built premises in Lincoln Center, and launched the new Met in September 1966 with the world premiere of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra. The new theatre boasted state of the art stage machinery (which however proved both technically more challenging and much more expensive than expected), extensive storage and rehearsal space, and two massive murals by Marc Chagall.

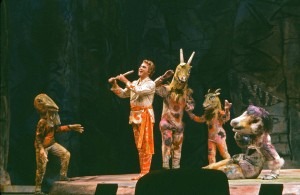

While Bing was never a stranger to recruiting celebrated Hollywood and Broadway directors to take control of a production, he scored a true coup by recruiting Marc Chagall to produce the stage sets for the first Zauberflöte of the New Met, creating a production that saw eight revivals. He was also the first Met impresario to enlist the support of a corporate sponsor for a production, convincing Eastern Airlines to underwrite Karajan’s Ring cycle.

Sutherland / Pavarotti – Lucia

Chagall the Magic Flute

Credit: Louis Mélançon/Metropolitan Opera

After stepping down, he seemed to lose his way. His long standing wife, a Russian ballerina, died in 1983. In 1987, the then 85 year old married a forty years younger woman with a history of mental illness. Suffering from Alzheimer’s, Bing needed the intervention of friends and a court ruling to annul the marriage.

At his death in 1997, the many obituaries were in agreement: Sir Rudolf was the first great opera impresario in a suddenly globalized opera world. He liked to portray himself slightly differently: “You don’t need wit to run an opera house,” he once quipped. “You need style.” His legacy proved that he had both in spades, along with a cold sense of business control.

Rudolf Bing Farewell