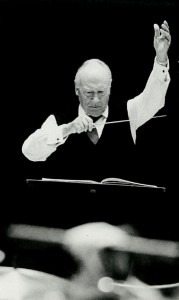

Paul Sacher

Sachers’ primary concern as a musician and conductor was to make contemporary works accessible and understandable for his audience. As such, his concert programming subtly juxtaposed old and new works. And his commissioned repertory reflected much of the musical history of the 20th century. Ranging from neo-baroque and neo-classicism to 12-tone music and atonality, Sacher was primarily interested in formal discipline, rhythmic vitality, musicality and a sense of melody and color. It is hardly surprising that most of the composers he commissioned wrote for the musical theatre, bringing a sense of dramaturgy to the orchestral stage. Yet, Sacher also had his detractors. For one, he had a special distaste for the piano, and proponents of the Second Viennese School were dismayed by his lack of enthusiasm and understanding for the music of Berg, Schoenberg and Webern. When he was challenged for overlooking the work of John Cage or Luigi Nono, he unapologetically replied, “I’m not the radio. I do not have to be fair.”

Sacher not only premiered the works he commissioned, but they became an integral part of the orchestra’s repertory. He took them on tour throughout the world, and introduced them to a wider public through radio performances and recordings. In 1973, Sacher purchased the music estate of Igor Stravinsky and established the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel. It houses some of the world’s most important collections of musical manuscripts, including the complete musical sources by Lutosławski, Ligeti and Boulez. Also containing a large number of unpublished musical manuscripts, the Sacher Foundation is one of the most important centers for the study of 20th-century music. The foundation continues to facilitate and support scholarly research, and supports a number of special projects and publications.

While it is almost impossible to describe Sacher’s exceptional importance to music and culture of the 20th century, we may nevertheless glimpse his significance via a sample of representative commissions. To celebrate the 20th anniversary of the founding of the Basler Kammerorchester, Sacher approached Igor Stravinsky. The composer responded with his Concerto in D, his last tonal work. Like previous compositions, Stravinsky appropriated the music styles of earlier composers as the raw material for this work. It was first performed on 27 January 1947 in Basel.

Igor Stravinsky: Concerto in D

Before immigrating to the US in 1939, Béla Bartók delivered his Divertimento for String Orchestra to Sacher. Composed within a fortnight, Bartók responded to Sacher’s request for a work that mirrored the spirit of eighteenth-century music. Rustic fold dances pay homage to the concerto grosso conventions of earlier times, while the central “Adagio” presents an example of Bartók’s characteristic “Night music.”

Béla Bartók: Divertimento for String Orchestra

When Richard Strauss was unable to get travel permission from the Nazi government in 1944, Paul Sacher quickly commissioned a work for his ensemble and issued a personal invitation to the composer for the premier in Zurich. As such, Strauss composed Metamorphosen during the closing months of the Second World War. One of his most technically complex and emotionally moving compositions, Strauss weaves together four themes to produce an extended symphonic adagio. Although it is commonly believed that Strauss wrote the work as a statement of mourning for the destruction of Germany during the war, he inadvertently composed a musical moment for culture. What is more, together all these composers created monuments to the musical vision of Paul Sacher!

Richard Strauss: Metamorphosen