Sendak: The Nutcracker

We remember him for Little Max and the Wild Things, but artist and author Maurice Sendak (1928-2012) has shown us more than just Where the Wild Things Are. His stage works include both opera and ballet sets.

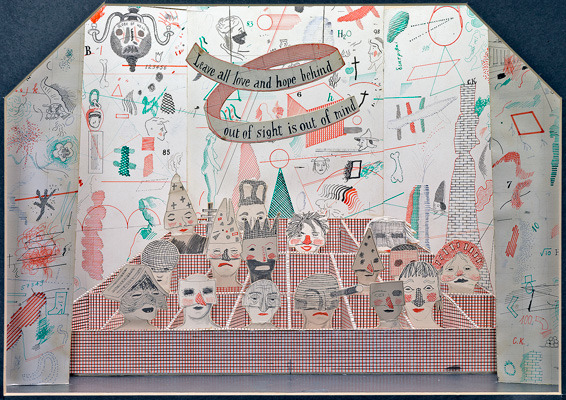

PNB: Clara and the Fully Grown Christmas Tree

His work for the Pacific Northwest Ballet company in 1983 resulted in a wonderfully imaginative Nutcracker that removes us from the late-nineteenth century world of most productions to take us into a child’s imagination. He worked with Kent Stowell at Pacific Northwest Ballet to return the story to the original setting imagined by E.T.A. Hoffmann. The original ballet by Tchaikovsky was based on an 1844 adaptation of Hoffmann’s story by Alexander Dumas. Stowell and Sendak brought back one of the original themes in Hoffmann’s tale: a child’s anxiety about growing up.

Program cover for Houston Grand Opera – who is receiving the bells from the Drei Knaben?

This change in the story reflects, in a very central way, the change in the audience for the ballet. It has largely become the annual fund-raiser for most ballet companies, employs every baby ballerina and boy dancer in the area, and is largely pitched at children and their parents. The original audience would have been adults who went, not for the story line, but for the chance to see fabulous dancing and women’s legs. So, Sendak made the sets much more child-oriented. The Sendak Nutcracker ran at Pacific Northwest Ballet for over 30 years before being retired in 2014.

Opening scene of The Magic Flute

In opera, he worked with Houston Grand Opera on The Magic Flute (1981) and Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel (1997). With the Los Angeles County Music Center, he did Mozart’s Idomeneo in 1990.

Mozart: Die Zauberflöte: Act I: Zu Hilfe! Zu Hilfe! (London Classical Players; Roger Norrington, cond.)

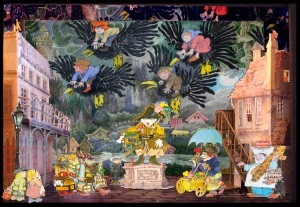

He designed both sets and costumes for New York City Opera’s production of Janáček’s The Cunning Little Vixen in 1981.

Sendak: Illustration for Idomeneo

Janáček: The Cunning Little Vixen Suite (arr. P. Breiner): III. Jsem opravdu tak krasna? (Am I Really that Beautiful?) (New Zealand Symphony Orchestra; Peter Breiner, cond.)

Prokoviev’s The Love for Three Oranges and 2 one-act operas by Ravel were also in his opera repertoire.

The Vixen, the Fox and other Animals

Prokofiev: The Love for Three Oranges Suite, Op. 33bis: III. March (Philharmonia Orchestra; Nikolai Malko, cond.)

On his own, he took Czech composer Hans Krása’s children’s Holocaust opera Brundibár and remade it for a new age. Sendak’s designs combined with playwright Tony Kushner’s new English version brought a new children’s opera into the repertoire. Brundibár had been written in 1938 for the children at an orphanage in Prague. When the entire orphanage was sent to the Theresienstadt concentration camp, work continued on the opera and it was produced some 55 times at the camp.

A chorus from the original Brundibár can be seen in this documentary starting at 04:41, which had been filmed as part of a German government propaganda film showing the fictitious prosperity of the residents of Theresienstadt.

Sendak: Love for 3 Oranges illustration

The story is about two children who need to find some money to buy needed milk for their mother but who are thwarted in their attempt to sing on the street by Brundibár the organ grinder who drowns out their music. When the two children are joined by animals and children, they, in turn, defeat the organ grinder’s sound and raise the needed milk money.

Set design for Sendak’s Brundibar – the 2 children are at the bottom left and Brundibar is stage centre

Krasa: Brundibár: Act II: Finale (Stuttgart Collegium Iuvenum; Stuttgart Madchenkantorei an der Domkirche St. Eberhard; Friedemann Keck, cond.)

Sendak’s designs for opera and ballet return us to a sense of childhood. It’s not always fun, it’s not always safe, but it is a time when we form our later selves. By mixing his imagination of childhood and the ostensibly adult genres of opera and ballet, Sendak has given us another view into the wonder that we used to have.