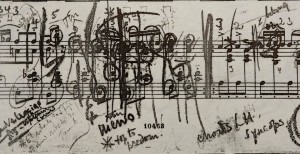

Clifford Curzon’s score of Schubert’s F minor movements from the Moments Musicaux

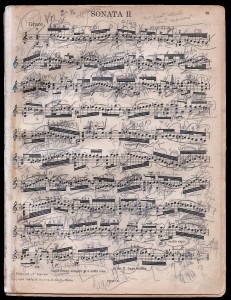

On a most basic level, markings on the score relate to fingering schemes, dynamics, pedaling and so forth. Learning music is a complex mental and physical process, and anything that assists in that process is useful. Often it is simply not possible to remember all the details in the music and annotations provide a useful aide memoir and an immediate mnemonic for the practice of practising. The permanence of the graphite pencil mark is such that, until we choose to erase that mark, it remains there on the page in front of our eyes.

Yehudi Menuhin’s annotated score of Bach’s solo Violin Sonata No. 2 (source: The Strad magazine/website)

Schubert: Piano Sonata No 20 in A, D959

Murray Perahia

Returning to a score after a break from it and reacquainting oneself with its annotations can be an interesting experience in itself. In a way, the annotations become a snapshot of a time and place. I’ve still got my old Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music editions of Bach’s Preludes and Fugues and Two- and Three- Part Inventions and Chopin’s Nocturnes, which contain annotations from the piano teacher I studied with as a teenager. Just seeing her handwriting and her diagram of the structure of a fugue, elicits a kind of Proustian rush, which takes me back to her living room, her big black Steinway, and her spaniel who used to lie across my feet as I played.

As I’ve become more experienced and mature as a musician, I write far less on the score than I used to, and lately when I return to a score I’ve previously worked on, I find myself erasing old annotations to clean up the score and make way for new, but fewer, markings. Some people like to keep one score completely free of markings and will work from a photocopy or duplicate copy of the score, so that they have a clean score for performance. Others like to cover their scores with so much annotation that the music is almost obscured, and some of us regard our scores and their individual markings as a kind of “comfort blanket”. My Henle edition score of Schubert’s sonata D959, now missing its smart blue cover, with dog-eared corners from turning the pages and many pages secured with tape, is a prized possession and one which I would hate to lose. It was, and still is, my working score and represents 20 months of hard graft, note-learning, study and thought. I can’t bear the thought of replacing this score!

Modern technology now allows us to annotate scores directly on a tablet device, and while this offers a tidy, portable means to do so (particularly useful when one is travelling), I suspect most musicians would be reluctant to completely relinquish pencil and paper score.