Marcel Tabuteau

Credit: Wikipedia

One of the most influential oboists of the twentieth century was Marcel Tabuteau (1887-1966), originally from France, but settling in the USA in 1907, where he became a citizen in 1912. After studying at the Paris Conservatoire, Tabuteau became principal oboist of the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1915, where he stayed until 1954, working closely with musical director Leopold Stokowski. During his time in Philadelphia, Tabuteau was appointed professor of oboe at the newly founded Curtis Institute of Music in 1924, a post he retained until his retirement in 1953.

Tabuteau is credited with founding the ‘American’ oboe sound that is still influential in teachings across the country today. This is largely down to his refinement of a new style of reed, made by employing the aptly named ‘Tabuteau scrape’ method. This took hold as a standard way to make reeds in the US, which then found its way into orchestras around the country, as Tabuteau’s graduating pupils found their way into various orchestral jobs nationwide.

Marcel Tabuteau: Handel, Oboe Concerto No.3 in G Minor

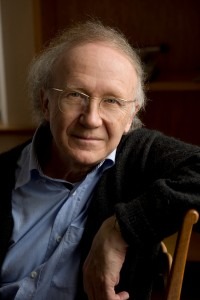

Robert Bloom

Credit: http://robertandsaralambertbloom.com/

A pupil of Marcel Tabuteau, American Robert Bloom (1908-1994) is considered vital in the development of American oboe playing. Studying with Tabuteau for three years at the Curtis Institute (where he no doubt picked up the Tabuteau scrape) preceded his tenure at the NBC Symphony Orchestra, of which he was principal from 1937 to 1943, playing under the infamous Arturo Toscanini.

He was assistant principal oboe at the Philadelphia Orchestra under Leopold Stokowski and during his time in both orchestras he can be heard on many recordings with Stokowski, Bernstein, and Stravinsky, to name just a few. To many, Robert Bloom embodied the American oboe sound, and on the many recordings on which he features, his distinctive Tabuteau-esque sonority can be heard shining through the wind section.

In 1946, Bloom was one of the founding members of the Bach Aria Group, an ensemble with whom he played until the group disbanded in 1980. A professor at both Yale and Juilliard, Bloom cultivated his own generation of young oboe players who now, today holds major positions in orchestras across the USA.

Philadelphia Orchestra (feat. Robert Bloom): Bizet, Symphony in C – Adagio

Heinz Holliger

Credit: https://i.scdn.co/

One of the most famous oboe soloists of the twentieth century, Swiss oboist Heinz Holliger (b.1939) won first prize in the International Geneva Competition aged just 20 years. His international career took off shortly after, and he became one of the leading exponents of the oboe, not least due to the number of new works written for him. An incredible body of contemporary oboe music exists thanks to Holliger, with composers including Olivier Messiaen, Toru Takemitsu Luciano Berio, Krzysztof Penderecki, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Witold Lutosławski and Elliott Carter all writing works with Holliger in mind.

Not only did Holliger achieve fame as a soloist; he lent his hand to composing in 1963, and never looked back. Over 170 pieces later, he continues to write to this day, recently winning the 2017 Robert Schumann Prize in the city of Zwickau for his contribution to international musical life.

Away from his work in new music, Holliger’s 1972 recording of Jan Dismas Zelenka’s six Trio Sonatas for Oboe and Bassoon with bassoonist Klaus Thunemann and continuo player Christiane Jaccottet sparked a revival in interest in Zelenka’s music. This adds to Holliger’s large discography, ranging from Mozart, Bach and Bellini through to Richard Strauss, Takemitsu and Stockhausen.

Lothar Koch

Credit: https://img.discogs.com/

Epitomising the dark, rich sound of the oboe for which Germany is famous, Lothar Koch (1935-2003) began his tenure as principal oboe of the Berlin Philharmonic in 1957, aged just 22.

He was a co-founder of the Soloists Ensemble of the Berlin Philharmonic in 1961, and in 1978 founded the Wind Ensemble of the Berlin Philharmonic with the other wind players of the orchestra. In a similar way to Tabuteau’s influence across the pond, Koch’s work in the Berlin Philharmonic’s Academy from 1972 and his eventual professorship at the Salzburg Mozarteum from 1991 sent out into the world a new generation of oboe players immersed in the sound that came to define one of the world’s greatest orchestras.

It is fascinating that there are a lot of orchestras that use the oboe. The oboe is definitely a very relaxing instrument to listen to.

I guess for me, as an oboist, I am very critical of others as I know what it takes. there are great players all over the world. I love Leon Goosens an Englishman, I love some of the great American oboists. And I am glad it is a relaxing instrument to listen to. keep listening! In my older years and becoming less prejudiced I am learning to appreciate the different but sometimes beautiful playing of the Europeans. I see different reed styles, different embouchures, etc. but I try to listen for the musicianship above all. all full-time orchestras have oboes, as do the semi-professional and part-time orchestras even. I feel privileged and know I was lucky to have a life of playing music. I am thankful.

excuse me, as an oboist who made living as a symphony oboe player, I really don’t agree with you. When played beautifully it is wonderful. But rarely do you find the gorgeousness of a Ray Still, or Marc Lyfshe. Most oboe sounds just are not there. I suffer when I listen to many oboists, many of whom have high positions in symphony orchestras. The oboe is rarely taught properly and most players play with too much tension. One in particular, who is quite famous, has a horribly strident sound in person, but uses all sorts of recording techniques to soften his sound so it’s not ear splitting on recoredings. The oboe is impressive, and can be very exciting, it can be beautiful and wonderful, Listen to Solti conduct la Scala di Seta, but for me it has never been relaxing to listen to except it can be enjoyable if played by a few great oboists, a small handful; and maybe that’s because I am too close to it and know what it takes to play it and why , in my 70’s now, I still work at it to get a good reed, and to come close to sounding the way I want to sound.