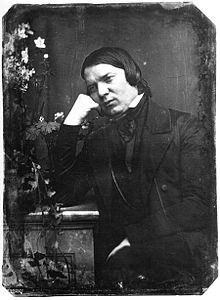

Schumann

The Festival became an important stage for the performance of world and national premieres. Beethoven’s 9th had its German premiere in 1825, as did Handel’s Samson in 1820. Mendelssohn’s oratorio St. Paul premiered in 1836, and Max Bruch first brought his Violin Concerto Op. 26 to the world stage in Düsseldorf in 1866. However, the Festival was not only concerned with the performance of new works, it also presented a number of up and coming, and highly established artists. Frédéric Chopin performed in 1834, Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale was discovered in 1846, Joseph Joachim featured on a number of Festivals, and the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche tried his luck as a singer in 1865! Since political troubles around mid-century had forced the cancellation of some Festivals, the 1853 event pulled out all the stops. And Robert Schumann, the municipal music director in Düsseldorf was chosen to lead the event.

The 1853 festival opened with the premiere performance of Schumann’s revised Fourth Symphony, paired with Handel’s Messiah. The second day included works by Weber, Mendelssohn, Hiller and Gluck, and concluded with a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth symphony. The soloist’s concert featured Clara Novello, Clara Schumann playing Robert’s piano concerto, and Joseph Joachim in a performance of the Beethoven violin concerto. The Festival concluded with Schumann’s Rheinweinlied, Op. 123, specially composed for the occasion. Schumann conducted the first day’s performances, and Ferdinand Hiller conducted on days two and three. An English visitor provided the following report for the Musical Times. “For those who were partakers in this delightful meeting, there remains an unfading recollection of excellent music enjoyed at leisure, associated with the beaming and friendly face of appreciating listeners. The executants and audience have an equally large appetite for music…”

Although the overall atmosphere of the event was cheerful and laid back, Schumann’s conducting on day 1 was deemed an embarrassment. “Regarding the performance of the Messiah,” one critic wrote, “we have seldom heard one that is more inadequate. Schumann possesses absolutely none of the characteristics that qualify a practical conductor; least of all does he understand how to lead large forces securely. It is already well known in Düsseldorf, indeed very well known, and we have only spoken clearly what others have until now dared only to insinuate. Issues of conducting technique aside, Schumann’s conception of the oratorio was no less inadequate, it was faulty and the execution, with few exceptions, practically disgraceful.” In fact, Schumann’s inability to make his musical intentions known to the musicians prompted the performers to privately agree to ignore him and follow the lead of concertmaster Hartmann instead. And when a friend congratulated Schumann after the performance, he dryly responded “Oh, one only congratulates women after childbirth.” Schumann would attempt suicide less than a year later, but the “Lower Rhine Music Festival,” with some substantial interruptions, was held until 1958. It was organized for a total of 112 times. Meanwhile, Schumann’s Fest-Ouverture mit Gesang über das Rheinweinlied für Orchester und Chor, Op. 123 has virtually disappeared from sight; not even NAXOS is able to provide a recorded performance!

Robert Schumann: Symphony No. 4, Op. 120