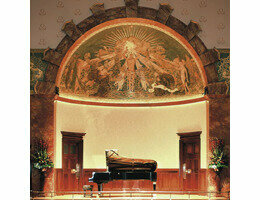

Wigmore loggia

Credit: https://crosseyedpianist.files.wordpress.com/

Opened on 31 May 1901, Wigmore Hall, nestling unobtrusively just a stone’s throw from the bustle and litter of Oxford Street in a row of tall Edwardian façades, is London’s pre-eminent venue for chamber music, song recitals and solo piano concerts. It was built to provide the city with a venue that was impressive yet intimate enough for recitals of chamber music. With near-perfect acoustics, the hall quickly became celebrated across Europe and featured many of the great artistes of the 20th century.

Originally called Bechstein Hall, it was built by the German piano manufacturer Carl Bechstein, whose busy showroom was next door. At the turn of the twentieth century, Bechstein was Europe’s leading piano maker, its instruments preferred by most pianists outside America, where Steinway predominated. The Bechstein piano company built similar concert halls in Paris and St Petersburg to showcase its instruments and the leading performers and singers of the day. With its special barrel roof “shoebox” design, beloved of many musicians, the hall boasts a fine acoustic, while its small size (its capacity is c600 seats) makes it the perfect place to enjoy intimate chamber recitals.

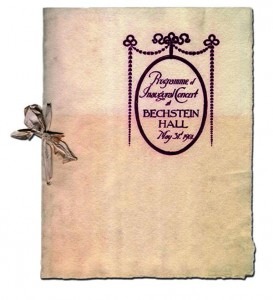

When it opened, Bechstein Hall was promoted as the best of places for intimate music making, and boasted unrivaled comfort and facilities for patrons and artists with its elegant green room up a short flight of stairs behind the stage (so that singers did not arrive on stage breathless). At the time of its opening, concert life and leisure in general in London were enjoying something of a revolution. Theatres and music halls were opening across the west end, a wide public was being introduced to the experience of shopping for pleasure in the new “department stores” (Selfridges is a mere 10 minute walk, at the most, from Wigmore Street), and with cheap and efficient public transport, it was easy for people to enjoy these delights in the centre of the metropolis. A new breed of international concert promoters, agents and impresarios, such as Robert Newman, who with conductor Henry Wood founded the world-famous Proms, were dedicated to organising high-quality recitals, and Bechstein Hall alone scheduled two hundred concerts. The opening concert on 31 May 1901 featured the virtuoso pianist and composer Ferruccio Busoni and violinist Eugène Ysaÿe; soon London’s concert-going populace were flocking to Bechstein Hall to see Frank Merrick and Leopold Godowsky, Artur Schnabel, Chopin specialist Vladimir de Pachmann, Camille Saint-Saens, Max Reger and ‘Valkyrie of the Piano’, the Venezuelan lady pianist Teresa Carreňo. The hall continues to enjoy special associations with leading international performers.

The hall was designed by architect Thomas Edward Collcutt who also designed the Savoy Hotel on the Strand. The interior is Renaissance style, with marble and alabaster walls, and above the small bell-shaped stage is a beautiful Arts and Crafts freize designed by Edward Moira depicting the Soul of Music. In the lights of the hall, the freize vibrates with the burnished radiance of a Byzantine mosaic.

The hall was designed by architect Thomas Edward Collcutt who also designed the Savoy Hotel on the Strand. The interior is Renaissance style, with marble and alabaster walls, and above the small bell-shaped stage is a beautiful Arts and Crafts freize designed by Edward Moira depicting the Soul of Music. In the lights of the hall, the freize vibrates with the burnished radiance of a Byzantine mosaic.

During the First World War, it became increasingly difficult for Bechstein Hall to trade viably. Strong anti-German sentiments and the passing of the Trading with the Enemy Amendment Act 1916 led in June 1916 to the hall’s closure, and all property including the concert hall and the showrooms was seized and summarily closed. The hall was sold at auction to Debenhams, was rechristened Wigmore Hall and opened under its new name in 1917.

Today the hall enjoys a position of pre-eminence not only in London but across the international classical music scene, and a debut at Wigmore Hall is the long-held dream of many young and up-and-coming performers.

Alongside its reputation for chamber music of the highest quality, the Wigmore’s audience is famous for its loyalty, intelligence and discernment. It is considered by many musicians to be one of the most demanding audiences of any concert hall, which brings its own unique set of pressures, and many performers will play a programme in regional venues and for local music societies before “doing a Wigmore”. But the hall holds a special place in the affections of many performers, who regard it as their artistic home in London.

There are no rough edges in this beautifully proportioned, perfect shoe-box of a hall, no jarring modern architectural details to confuse and distract. The tread of the thick crimson carpets is complimented by the red Verona marble frieze, the bustle of Oxford Street and the West End forgotten in the spacious vestibule and elegant green room. Playing at the Wigmore or being in the audience, one feels a sense of history, of heritage, for the Wigmore inhabits a different era and ethos to other concert venues in London. All the time one is aware of the great performances that have taken place in the hall, and the walls of the green room are lined with photographs confirming the heritage of the hall: Rachmaninoff scowling, as if the last thing he wanted to do was play the piano, Britten’s severe stare, Tippett’s twinkling eyes.

As a member of the audience, attending a concert at the Wigmore has its own special rituals from the moment one steps through the glass doors. The richly-carpeted vestibule is a place where people meet, queue for tickets, purchase programmes, CDs or magazines. Sometimes if you arrive early, you might hear the soloist warming up, and that can lend a special frisson to the evening, a glimpse of what is to come. Downstairs the bars and restaurant resonate with pre-concert conversations, and sometimes when I am there with friends we might spot a “musical celebrity” – Steven Isserlis, Alfred Brendel, Julian Lloyd Weber. I usually arrive in good time for drinks and chat with friends before the bell summons us to the hall and we happily sink into the plush comfort of the crimson seats. In the auditorium, in the moments before the concert begins, one senses the great collective breath of the audience’s expectation.

People, usually those who have never stepped inside the Wigmore let alone enjoyed a concert there, grumble about the great age of the audience, but this fiercely loyal audience is what makes the hall – for without an audience there is no such thing as a “concert”. In fact, the Wigmore audience is getting younger and more diverse as the hall has broadened its remit. Today, in addition to lunchtime, evening and Sunday morning “coffee concerts” (where the ever-popular sherry is served after the concert), Wigmore Hall offers a lively education programme, music for small babies and toddlers, and “Wigmore Lates”, concerts which start at 10pm and include not just classical music but jazz and folk too. There are masterclasses and study days with leading performers and composers on subjects such as Schubert’s last piano sonatas and coping with performance anxiety. And on the annual London Open House Weekend visitors can explore the backstage area and even take to the stage, momentarily at least, and maybe dream of playing to a full house…..

Joyce DiDonato and Antonio Pappano Live at Wigmore Hall