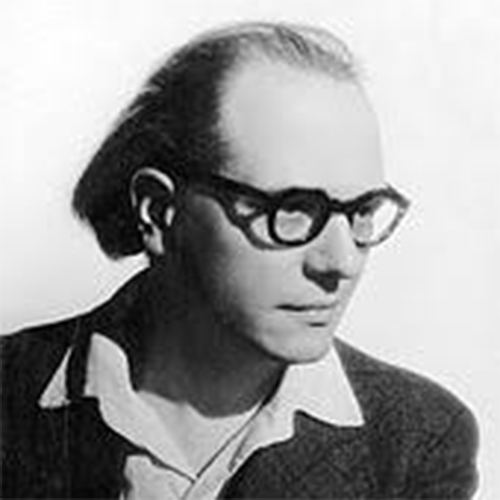

Olivier Messiaen

It is, above all else, an expression of Messiaen’s deeply-held Catholic faith – even more so than the Quatuor pour la fin du temp (Quartet for the End of Time) – a faith which involved sound and silence, beauty and terror, joy, love and an all-embracing sense of awe. It is music that puts listener and performer in touch with something far greater than ourselves, and yet one does not have to have religious faith to appreciate the enormity and emotional breadth of this work. Messiaen has an unerring ability to “ground” the music in a way that makes it more accessible through his use of recurring motifs and devices, in particular his beloved birdsong. These elements also give this tremendous work a cohesive, comprehensive structure – and it is only by hearing the work in one sitting, as opposed to listening to individual movements from it, that one can fully appreciate Messiaen’s compositional skill and vision. Like a great symphony, the work moves inexorably through its movements towards a gripping finale.

The Theme of Chords

All twenty movements are constructed around three distinctive themes. The first, the Theme of God, a slow-moving chordal motif, heard first in the opening Regard (Regard du Père/Gaze of the Father). It recurs in Regards V, XI and XV, and is always sonorous, luminous and profound. The second theme, the Theme of the Star and the Cross, first appears in Regard II. Turbulent and fractured, it signifies the beginning and the end of Christ’s life. The final theme, the Theme of Chords, is a sequence of four chords which are used in various ways throughout the entire work, most obviously in Regard XIV. In the final movement, all three themes are brought together.

Silence also plays a significant role in the music, never more so than in the penultimate movement where the sonorities, resonance and sound-decay of the modern piano are utilised with highly arresting effect. In some movements, the silences are like breaths or moments of hushed contemplation. Birdsong plays a meaningful part in many of the movements too (Messiaen was a devoted ornithologist), with chatterings and squawks, trills and shrills in the upper registers, always used melodically rather than for pure effect. There are even references to Gershwin’s ‘I Got Rhythm’, a joyous, jazzy outpouring in Regard X (Regard de l’Esprit de joie/Gaze of the Spirit of Joy), and later a hint of ‘Twinkle Twinkle Little Star’.

Another important aspect is Messiaen’s “flashes”, colourful chords and clusters of notes or fragments which reflect Messiaen’s belief that it was only possible to comprehend the totality of God in “flashes”. To me, these are akin to the lines of stigmata found in paintings by artists such as Giotto, as well as the golden halos and symbolic devices found on Greek and Russian Orthodox icons. In the music we also hear tolling bells and carillon chimes, complex rhythmic motifs, and references to devotional texts, numerology, and Hinduism, as well as deeply portentous passages, suggesting Jesus’s fate. These aspects informed much of the composer’s thinking and became recurring elements in his later works. It was the last piece of sacred music Messiaen would write until 1960, and is the only sacred work he wrote for solo piano. It also holds the rather special distinction of being the longest piece of solo sacred piano music ever written (Liszt’s Harmonies poétiques and religieuses is the next longest, at 90 minutes).

The composer gives very clear directions and markings in the score to help the performer understand both the context of the music and the kind of sound he envisaged. For example, the recurring themes are marked each time they appear, and Messiaen indicates particular instruments too: the xylophone Regard de la Vierge, bells in Noël, and the tam tam (a gong-like instrument) and oboe in Regard des prophétes, des bergers and des Mages.

At two hours in length, the work is rarely performed in full, and it is not for the faint-hearted. It takes a special kind of performer who has the physical and emotional stamina and focus to undertake such a task for it places immense technical and musical demands on the pianist. The expressive sweep of the work is vast, from the intimate, aching tenderness of Regard de la Vierge (IV) to primal brutality of Par Lui tout a été fait (VI) and the concentrated stillness of Je dors, mais mon coeur veille (XIV).

Messiaen’s Vingt Regards sur l’enfant Jésus

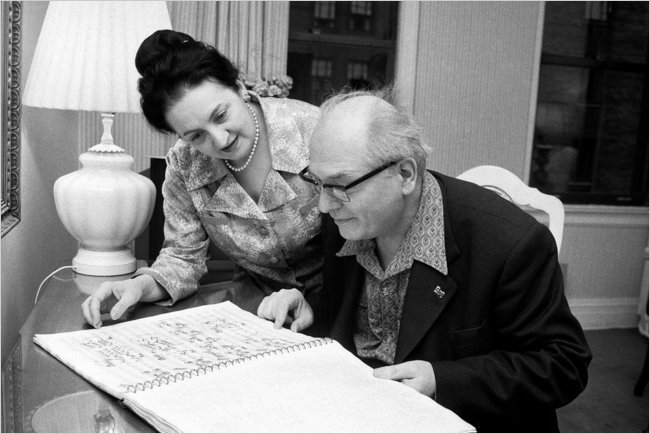

Piano: Yvonne Loriod