The New Year’s concert by the Vienna Philharmonic is commonly regarded as the most important classical concert worldwide. Seen by an estimated audience of 1 billion viewers around the world, the concert always features works by the Viennese Strauss family, and various other composers connected to the city. Held in the Golden Hall of the Musikverein, television images include ballet performances danced by the Vienna State Ballet at various famous places in Austria including Schönbrunn Palace, Schloss Esterházy, the Vienna State Opera or the Wiener Musikverein itself. And one of the regular encores, the Blue Danube Waltz by Johann Strauss Jr., habitually features ballet performances. One of the most recognizable tunes of all times, the Blue Danube Waltz takes its name from a poem by Karl Beck, and was originally scored for four-part choir and orchestra. It was rather unsuccessful in that particular version, so Strauss Jr. revised it a couple of times before turning it into a purely instrumental composition. In this form, it features five distinct mini-waltzes prefaced by a slow introduction, and it propelled Johann Strauss Jr. to international stardom at the Paris Exhibition of 1867.

The New Year’s concert by the Vienna Philharmonic is commonly regarded as the most important classical concert worldwide. Seen by an estimated audience of 1 billion viewers around the world, the concert always features works by the Viennese Strauss family, and various other composers connected to the city. Held in the Golden Hall of the Musikverein, television images include ballet performances danced by the Vienna State Ballet at various famous places in Austria including Schönbrunn Palace, Schloss Esterházy, the Vienna State Opera or the Wiener Musikverein itself. And one of the regular encores, the Blue Danube Waltz by Johann Strauss Jr., habitually features ballet performances. One of the most recognizable tunes of all times, the Blue Danube Waltz takes its name from a poem by Karl Beck, and was originally scored for four-part choir and orchestra. It was rather unsuccessful in that particular version, so Strauss Jr. revised it a couple of times before turning it into a purely instrumental composition. In this form, it features five distinct mini-waltzes prefaced by a slow introduction, and it propelled Johann Strauss Jr. to international stardom at the Paris Exhibition of 1867.

Johann Strauss Jr.: Blue Danube

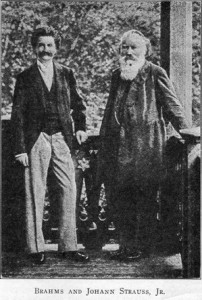

Without doubt, Strauss Jr. was the most famous bandleader of his time. For a period of more than 40 years he conducted an exquisite dance and salon orchestra and inspired a champagne induced dance craze that enveloped the entire continent. Although it was easy to dismiss him as a musical lightweight, Strauss Jr. was greatly admired by Johannes Brahms and Richard Wagner. Brahms was genuinely interested in his music, and a famous anecdote relates that the wife of Strauss Jr. once asked Brahms for his autograph to put on her fan. Brahms immediately agreed and wrote the opening measures of the Blue Danube Waltz. He supposedly also put the words “not, alas, by Johannes Brahms.” And it was Richard Wagner who gave Strauss Jr. the title, “King of Waltzes.” He wrote in 1863, “A single Strauss waltz exceeds in finesse, charm and authentic musicality most of the painful factory products that come from abroad.” Even the ever-grumpy Vaughan Williams grudgingly conceded, “A waltz of Strauss is good music in its proper place.”

Without doubt, Strauss Jr. was the most famous bandleader of his time. For a period of more than 40 years he conducted an exquisite dance and salon orchestra and inspired a champagne induced dance craze that enveloped the entire continent. Although it was easy to dismiss him as a musical lightweight, Strauss Jr. was greatly admired by Johannes Brahms and Richard Wagner. Brahms was genuinely interested in his music, and a famous anecdote relates that the wife of Strauss Jr. once asked Brahms for his autograph to put on her fan. Brahms immediately agreed and wrote the opening measures of the Blue Danube Waltz. He supposedly also put the words “not, alas, by Johannes Brahms.” And it was Richard Wagner who gave Strauss Jr. the title, “King of Waltzes.” He wrote in 1863, “A single Strauss waltz exceeds in finesse, charm and authentic musicality most of the painful factory products that come from abroad.” Even the ever-grumpy Vaughan Williams grudgingly conceded, “A waltz of Strauss is good music in its proper place.”

Johann Strauss II: “Overture” Die Fledermaus (The Bat)

Strauss Jr.’s charming and effervescent music bathed in the golden splendor of the Viennese Musikverein or the Austrian countryside not only nostalgically harkens back to the glory days of the Empire, it also provides a sense of timelessness. It would be rather easy to assume that the New Year’s concert by the Vienna Philharmonic originated during Strauss Jr.’s lifetime in the 19th century. But that is simply not the case. While concerts on New Year’s Day had been held in Vienna since 1838, it had nothing to do with the music of the Strauss family. In fact, ever since its founding in 1842, there was simply no reason for the Vienna Philharmonic to perform mundane salon music. The first concert in the tradition of the New Year’s Day concert as we know it today was actually performed in 1939 and conducted by Clemens Krauss. And as you might gleam from the ominous date coinciding with the beginning of World War II, the concert was actually a political and cultural construct.

Strauss Jr.’s charming and effervescent music bathed in the golden splendor of the Viennese Musikverein or the Austrian countryside not only nostalgically harkens back to the glory days of the Empire, it also provides a sense of timelessness. It would be rather easy to assume that the New Year’s concert by the Vienna Philharmonic originated during Strauss Jr.’s lifetime in the 19th century. But that is simply not the case. While concerts on New Year’s Day had been held in Vienna since 1838, it had nothing to do with the music of the Strauss family. In fact, ever since its founding in 1842, there was simply no reason for the Vienna Philharmonic to perform mundane salon music. The first concert in the tradition of the New Year’s Day concert as we know it today was actually performed in 1939 and conducted by Clemens Krauss. And as you might gleam from the ominous date coinciding with the beginning of World War II, the concert was actually a political and cultural construct.

Johann Strauss Jr.: Morgenblätter (Morning Journals)

The idea of a seasonal Strauss gala emerged in the late 1920’s, but it was implemented when the National Socialist came to power. With support from the Vienna Gauleiter Baldur von Schirach, a New Year’s concert with orchestra—to be held on 31 December 1939—originally raised money for the Kriegswinterhilfswerk (Winter War Relief) to provide fuel for the needy during the cold winter months. The concert was billed as a unifying cultural event on New Year’s Day in 1941 and broadcast live across the Third Reich. Of course, Strauss’ Jewish ancestry was conveniently overlooked, and his music, alongside Richard Wagner’s, set up as a cornerstone of Germanic cultural achievement. When the war ended, the New Year’s concerts simply continued. For a variety of reasons, “invented traditions” like the New Year’s concert, the Christmas tree or the celebration of “Columbus Day” or “Thanksgiving” are deeply engrained in popular imagination and customs. Being cognizant of the frequently less-than-noble roots of such traditions does not necessarily take away from the spirit of artistic enjoyment or the sense of cultural belonging, but it should definitely function as a reminder that the course of human history is hardly a straight line.

The idea of a seasonal Strauss gala emerged in the late 1920’s, but it was implemented when the National Socialist came to power. With support from the Vienna Gauleiter Baldur von Schirach, a New Year’s concert with orchestra—to be held on 31 December 1939—originally raised money for the Kriegswinterhilfswerk (Winter War Relief) to provide fuel for the needy during the cold winter months. The concert was billed as a unifying cultural event on New Year’s Day in 1941 and broadcast live across the Third Reich. Of course, Strauss’ Jewish ancestry was conveniently overlooked, and his music, alongside Richard Wagner’s, set up as a cornerstone of Germanic cultural achievement. When the war ended, the New Year’s concerts simply continued. For a variety of reasons, “invented traditions” like the New Year’s concert, the Christmas tree or the celebration of “Columbus Day” or “Thanksgiving” are deeply engrained in popular imagination and customs. Being cognizant of the frequently less-than-noble roots of such traditions does not necessarily take away from the spirit of artistic enjoyment or the sense of cultural belonging, but it should definitely function as a reminder that the course of human history is hardly a straight line.