Lapo Vettori

To the uneducated eye, violins (and their ilk) look more alike than different. Yet, to Lapo, each instrument is distinctive. In looking at his family’s instruments, he can tell immediately not only who made it but also when it was made. He noted that over the last 20 years of his grandfather’s career in particular, he made distinctive changes. Grandfather Dario started the company, it was continued by his two sons Carlo (now retired) and Paolo, and now is continued by Paolo’s three children: Dario II, Lapo, and Sophia.

The Family shop in Florence

When we talked about the wood of the instruments, there are three principal woods used in any violin and viola: spruce for the top; maple for the back, neck, and sides; and ebony for the fingerboard. If it’s a cello, then the back is made of poplar, but that wood is too soft for the smaller instruments. Each year they source wood to add to their wood that is being aged, and, in the case of ebony, need to guarantee that the rare wood comes from sustainable sources. They were particularly fortunate a few years ago to get a supply of very old spruce – a Mantuan palazzo was being taken down and they secured wood that dated to 1600 and had been cut down in 1824, according to the dendrochronology (or tree-ring dating) report on the wood.

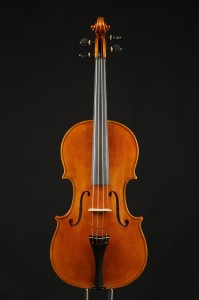

Lapo’s award-winning viola, front and back

One of Dario II’s cellos is played by Lithuanian David Geringas, who had been a student of Mstislav Rostropovich.

Čiurlionis: Nocturne in C-Sharp Minor, VL 183 (David Geringas, cello)

Violist Guan Qi of the Singapore Philharmonic plays a Vettori viola.

Lapo’s 2009 viola won the acoustics award at the XII Triennale of International Violin-making Competition “A. Stradivari” in Cremona.

Lapo’s award-winning viola, front and back

A Vettori ‘quartet’

Each instrument is approached with the question of “What’s Your Idea of an Instrument” because each piece of wood is different, each commissioner desires something different, and with every instrument he makes, the violin-maker further refines his definition of what the instrument should be. As a violin maker for the past 16 years, Lapo considers himself as a relative newcomer to the field and every instrument he makes takes him further along the path to the creation of his definitive masterpiece.