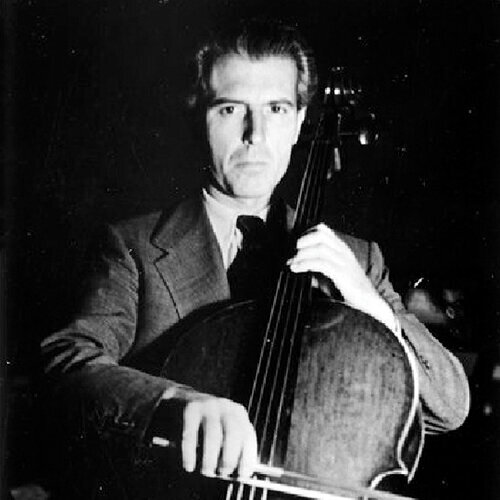

Frenchman Maurice Gendron (1920-1990) was known for his poise and elegant, pristine playing. If Daniil Shafran played with unconventional hand positions, Gendron’s are nearest to the ideal. His hands are cello perfect: rounded, relaxed, symmetrical, and produced a shimmering sound.

Frenchman Maurice Gendron (1920-1990) was known for his poise and elegant, pristine playing. If Daniil Shafran played with unconventional hand positions, Gendron’s are nearest to the ideal. His hands are cello perfect: rounded, relaxed, symmetrical, and produced a shimmering sound.

You can see for yourself in the unusual little video Métamorphose, which features excerpts of the Haydn Concerto in D major, Boccherini, Chopin, and the Sarabande movement from Bach Cello Suite No. 5 in C minor. There are views of his hands from every conceivable angle, even under his finger tips, and without the instrument. A fascinating bird’s-eye-view! Then the camera digresses to the making of a cello, from the felling of the tree, through the carving and shaping of the wood, to the final work of art.

Maurice Gendron: Métamorphose du violoncelle, directed by D. Delouche

Maurice Gendron came from a humble family. Very precocious as a child, Gendron could read music by the time he was three, and a violin was immediately thrust into his talented hands. But he would have none of it. He disliked the instrument, and preferred the cello! A three-quarter cello was found for him. Gendron began studies with Stephane Odero, and when a few years later the master cellist Emanuel Feuermann came to Nice to perform, Odero and the ten-year-old were in the audience. The concert made such a great impression on Gendron that he was moved to tears. Later he wrote about Feuermann’s influence on him, “I shall never forget the first time I heard him. It was quite unlike anything else I had ever heard. Not only was his technique wonderful but his playing was so honest. He never compromised…” (from The Great Cellists by Margaret Campbell.)

Although studies followed at the Nice Conservatoire and then the Paris Conservatoire, the indigent family could not afford to help Gendron, and he was forced to live in cold, unheated rooms and to eke out a living selling newspapers, but he could barely afford to eat. When the war began in 1939 he was given a medical deferment due to his compromised health. That didn’t stop him from defying the Nazis and joining the resistance.

Although studies followed at the Nice Conservatoire and then the Paris Conservatoire, the indigent family could not afford to help Gendron, and he was forced to live in cold, unheated rooms and to eke out a living selling newspapers, but he could barely afford to eat. When the war began in 1939 he was given a medical deferment due to his compromised health. That didn’t stop him from defying the Nazis and joining the resistance.

Meanwhile he played some private home concerts, rubbing shoulders with great artists and outstanding musicians of the time with whom he made life-long friendships —Jean Cocteau, Georges Braque, Marc Chagall, Pablo Picasso, and the composer Poulenc. He performed with pianist Dinu Lipati and with Jean Françaix, who became his long-term recital partner, he recorded the Beethoven and Brahms sonatas and numerous other works.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Cello Sonata No. 3 in A Major, Op. 69(Maurice Gendron, cello; Philippe Entremont, piano)

After the war ended, Gendron made his solo debut at Wigmore Hall in London, December 2, 1945 with the composer, Benjamin Britten at the piano, and that month he gave the European premiere in London, of the Prokofiev Cello Concerto No. 1 (Op. 58), establishing his international career.

Gendron’s New York debut was bittersweet—the memorial concert of Emanuel Feuermann, who had died tragically at the age of 39. Gendron performed the Dvořák and Haydn D Major Concertos.

Antonín Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104, B. 191 – II. Adagio ma non troppo (Maurice Gendron, cello; London Philharmonic Orchestra; Karl Rankl, cond.)

Numerous programs followed. He appeared as soloist, in recital, and as a member of the acclaimed string trio with Yehudi and Hepzibah Menuhin with whom he performed for over 25 years.

Among Gendron’s achievements is performing for the only commercial recording conducted by Pablo Casals—exquisite renderings of the Haydn and Boccherini Concertos with the Lamoureaux Orchestra. Casals appreciated the younger man’s playing and even had commended Gendron for not imitating his own interpretations of the Bach Suites. No-one expected Casals to conduct a fellow cellist but he had readily agreed. Gendron played from the original scores of the Haydn and Boccherini, which he had unearthed in the Dresden State Library purely by chance. The interpretation of the Boccherini is effortless—all breath and lightness, and the recording is still considered a classic.

While maintaining his solo career—recitals with pianists Rudolph Serkin and Philippe Entremont, recording the six Bach Solo Suites, and appearing as soloist with the orchestras of Vienna and London—like other cellists, Gendron tried his hand at conducting. He led orchestras in France, Portugal and Japan. He also held teaching positions at the Paris Conservatoire, at the Mozarteum in Salzburg, and from 1968 to 1977, the Yehudi Menuhin School in Surrey. It is said he was an exceedingly demanding teacher even to a fault. At one point allegations were made about his tyrannical, intolerant behavior towards his youngest students but no formal complaints were received by the school administrators.

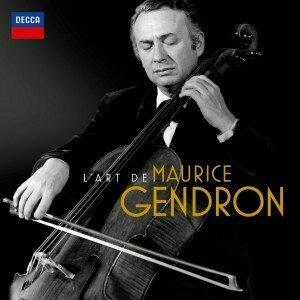

France awarded Gendron the Legion of Honor and the National Order of Merit. When he passed away in 1990, his Stradivarius cello, which has become known as the “Ex-Gendron” was loaned to German cellist Maria Kliegel. Gendron’s cello sound can be heard on a great many recordings and is described as expressive, airy, transparent, technically masterful, and always beautifully phrased. His cello methodology is illuminated in his book L’Art du Violoncelle, written in collaboration with Walter Grimmer, and published in 1999.

Poulenc: Sérénade from Chansons Gaillardes (2’)

Thank you for this biography of the stellar cellist that was Maurice Gendron, whose playing I have long admired for all the qualities you, as a professional cellist, understand and express so well. Indeed, his performances of the Boccherini and the Haydn concertos with Casals conducting are a treasure. I also have an indelible memory of Gendron playing the Dvorak with the Québec Symphony Orchestra conducted by Françoys (yes, with a “y”!) Bernier in the mid-1960’s. A Prokofieff March for an encore! Thank you again for the posting and the excerpts of Gendron’s wonderful playing.

Quite a puzzling title 🙁

Gendron is a very well known and appreciated cellist.