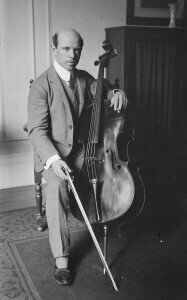

Gaspar Cassadó

Requiebros: Cassadó playing Cassadó

Dance of the Green Devil: Cassadó playing Cassadó

Cassadó was born in Barcelona in 1897 to a musical family. Joaquin, his father, was a composer and an organist. Cassadó was nine years old, when he played his first public performance: the great cellist Pablo Casals in attendance. Quite taken by the youngster’s talent, Casals offered to take Gaspar as a student, although at the time he had only three students. (One of them was Guilhermina Suggia.) Joaquin moved the family to Paris in 1907 after the city of Barcelona offered a scholarship to Gaspar for his studies. Agustin, the older son, was also very talented. While he studied with the famed pedagogue Jacques Thibaud, Gaspar worked with Casals and studied composition with French Impressionist Maurice Ravel, and fellow Spaniard, Manuel de Falla.

Cassadó idolized Casals and was greatly influenced by him. “Once, in Berlin in 1925, I went to a concert to hear Casals. The program included the Bach Fifth Suite. This unsurpassed interpretation had such a great impact on me…” Cassadó thought Casals should publish his edition of the Suites but Casals hesitated. Later Cassadó understood, “It is possible to assert that a great performer is an improviser at the same time. He never performs the same composition twice in the same way.”

The two brothers, Agustin and Gaspar, and their father Joaquín, concertized widely as a trio until the outbreak of World War I. They were forced to return to Barcelona, but Cassadó’s cello career flourished back home. He performed at the Palau de la Música Catalana with eminent artist Arthur Rubinstein and by 1921, he was recognized as one of Spain’s leading musicians. Cassadó performed in concerts with the Barcelona Symphony showcasing music of leading Spanish composers.

After the war Cassadó toured France and Italy, and his visibility as a composer increased. In 1928, Cassadó’s composition Rapsodia Catalana was premiered by the New York Philharmonic under the baton of William Mengelberg.

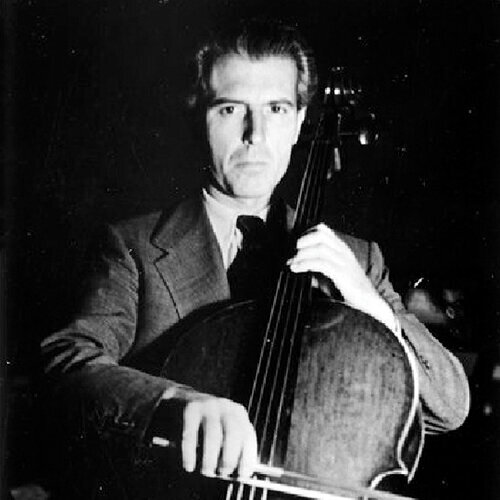

Pablo Casals

Cassadó: Cello Concerto in D Minor

Then a rift between the two cellists occurred, due to their differing political viewpoints. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, led Casals to refuse to perform in Spain under Fascism. He fled Barcelona in self-imposed exile. Perhaps Casals expected his pupils to follow suit, but Cassadó remained behind and continued to perform. In fact, he gave his New York debut that year in Haydn’s Concerto in D Major with the New York Philharmonic, John Barbirolli conducting. Cassadó maintained that he was “apolitical.” During the Second World War, Cassadó kept a low profile and continued living in Florence.

In 1949, Cassadó give a critically acclaimed New York recital but another Casals disciple, cellist Diran Alexanian, objected to Cassadó’s use of Casals’ name believing that Cassadó was a traitor to their cause. Casals was recognized for his humanitarian efforts, and he had given up his illustrious career to highlight Spanish Republican ideals and to fight totalitarianism. It is unclear whether or not Cassadó even performed during the war, and there is little evidence he was a collaborator. Nonetheless, in a letter to the New York Times, Casals castigated his former student, which served to drastically curtail Cassadó’s career. A contract to record with Columbia records was cancelled. The damage was done.

Years later, a reunion was facilitated by a close friend of both cellists—violinist Yehudi Menuhin. Cassadó invited Casals to give masterclasses at the Accademia Musica Chigiana in Siena, where Cassadó had been teaching since 1946. Cassadó also taught at the Musik Hochschule in Cologne in 1958, and with Andrés Segovia and Alicia de Larrocha, he founded a summer festival in Santiago de Compostela.

Gaspar Cassadó and Chieko Hara

Cassadó plays Schumann Cello Concerto in A Minor, Op. 129

A lover of experimentation, and attempting to increase the cello’s sonority, Cassadó was the first cellist to perform with steel strings, rather than gut. He invented a fingerboard which could be adjusted up or down to compensate for changes in bridge height, which tends to react to weather changes and can be quite troublesome to deal with. Most cellists have two bridges—one for winter and one for summer.

Cassadó composed nearly 70 transcriptions for cello and piano, including my favorites—Requiebros and Intermezzo from the opera Goyescas by Enrique Granados. Cassadó also composed three string quartets, several piano works, a sonata for violin, a sonata for cello, several guitar pieces, the orchestra work Rapsodia Catalana, as well as the brilliant Suite for Cello Solo.

Starker plays Cassadó Solo Suite Mov’t I

Cassadó plays: from Boccherini Sonata #6 Adagio

I have just listened to GC’s performance of the Dvorak concerto on VOX and enjoyed it hugely. As a consequence I searched for other CDs of performances by him. This led me to the website of MELOCLASSIC CDs ( meloclassic.com). Here I found a CD described as GC’s “Wartime German Radio Recordings” which are advertised as being made in Berlin in 1940 and Hamburg in 1944. If he chose to travel from Italy to perform in those cities in those years there appears to be more substance in the accusation of collaboration than your article envisages. I do not say this with any pleasure or political point-making, nor any desire to disparage GC or your article.

Cree el ladrón que todos son de su condición…

In 1959 Gaspar Cassadó married Chieko Hara, one of the first Japanese women pianists who performed steadily throughout Europe. After her husnand’s death in 1969 Ms. Hara started the Gaspar Cassadó International Violoncello Competition that is held every two years in Florence.