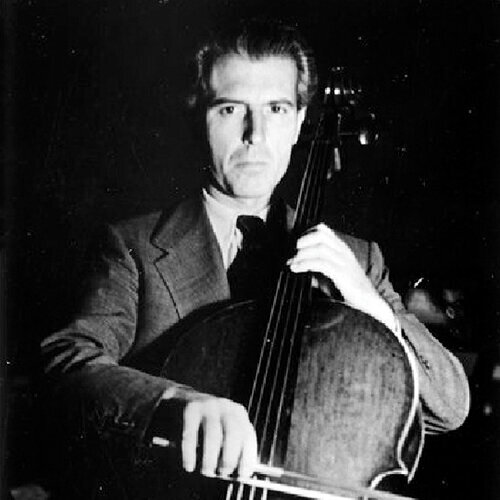

Hideo Saito

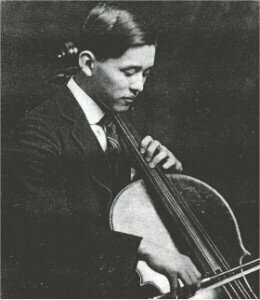

Hideo, born in Tokyo in 1902, was one of eight children of a prominent English literature professor. At the time, Western classical music was fairly unknown, but due to their father’s interests in languages and art, all of the Saito children learned a musical instrument. Initially, Hideo chose the piano and the mandolin, demonstrating his predilection for conducting when he conducted a mandolin orchestra as a teenager. At the age of 16, he turned to the cello.

An ardent student of languages, Hideo became fluent in German, English, French and Chinese but it was the cello that captured his heart. His friend Prince Konoye, a member of the Imperial Family, and conductor of a university orchestra was to change Hideo’s life. In 1923, Konoye invited Hideo to accompany him on a trip to Germany where they would both pursue their musical studies. Hideo’s father, averse to the idea, acquiesced. He could hardly refuse a member of the royal family.

Toho Gakuen School

Upon his return to Japan in 1927, Saito became the principal cello of the New Symphony Orchestra, appearing frequently as soloist. He formed the first chamber music organization in all of Japan. Not yet content with his cello-playing skills, Saito returned to Germany, in 1930, this time to study with Feuermann. For two years, Saito practiced like a mad man—his playing still not the standard of other cellists. Feuermann gave Hideo his complete attention. Saito never forgot, “I earnestly endeavor to provide even those students with lesser abilities the best I have to offer, and this is what I learned from Professor Feuermann.”

Hideo returned to Japan and resumed his position with the orchestra re-named the NHK Orchestra and by 1936, they were able to attract a fine conductor Joseph Rosenstock, who moved to Japan to take up the helm. After conducting in Germany for many years, Rosenstock had to flee Europe due to his Polish-Jewish heritage. (He would later make his way to New York and conduct the Metropolitan Opera.)

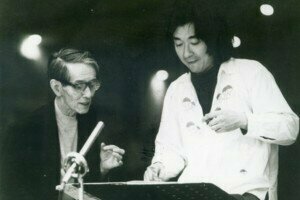

Hideo Saito and Seiji Ozawa

The Japanese people, avid patrons of the arts, were enthusiastic about learning western art forms. The solace of music was sorely needed after the war and it was the ideal time for Saito to promote Western music in Japan. First, he opened a school for conducting. Then he founded the Tokyo Chamber Music Association to promote chamber music performances.

In 1948, Saito established a music school for children, in bare bones classrooms rented from the Kasei Gakuin School in Tokyo. But instilling merely the rudiments of music was not enough. Saito was determined to expand, to continue the children’s music education into high school. The only suitable location for a music school was the Toho Girls’ High School but Saito insisted on a co-ed school and one that didn’t require uniforms. The establishment resisted. Gradually, Saito gained supporters and in 1952 a co-ed music course opened for students aged 15 to 18. By 1955, Toho Gakuen College was established as a two-year college. Saito took the position of chairman of the string and conducting departments. Six years later, broadening the music courses offered, Toho Gakuen School of Music became a four-year college.

Saito’s students initially found him overly demanding. Working with virtually all of the students his hands-on approach instilled disciplined rhythm and technique. When in 1964 Saito took the Toho Children’s Orchestra on tour to the U.S. and later the U.S.S.R. and Europe, the reception was overwhelmingly positive.

Ravel: Tzigane (version for violin and orchestra) Kishima Mayu and NHK Symphony Orchestra

Ashkenazy conducting

Famous graduates of the school include the founders of the Tokyo String Quartet, violist, Nobuko Imai, and cellist Tsuyoshi Tsutsumi, who began his studies with Saito and continued with Janos Starker. Japanese artists such as Kishima Mayu, are of the highest caliber and the NHK Symphony Orchestra attracts some of the greatest conductors and soloists, all due to the dreams of a young man, Hideo Saito, who influenced an entire generation of musicians.

Bach: St. Matthew Passion

Saito Kinen Orchestra, Seiji Ozawa

After his death in 1974, to pay tribute to him, two of his most famous students, Seiji Ozawa and Kazuyoshi Akiyama, gathered musicians whom Saito had trained and formed the Saito Kinen Orchestra. In 1992, after a successful world tour, the group established a festival in the Japanese Alps. The festival in Matsumoto, which takes place annually, now includes jazz as well as classical concerts and draws all types of music-lovers.

Hideo Saito (1966) 1 of 3 Britten Simple Symphony and working with youngsters