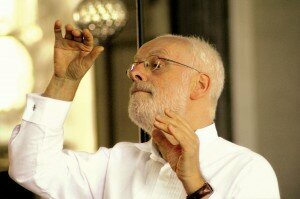

Ton Koopman

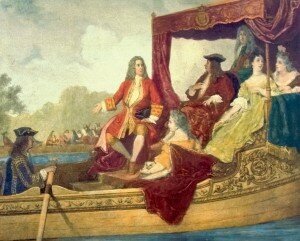

The Guangzhou concert will present both of the great orchestral works Handel wrote for George I (The Water Music) and George II (Music for the Royal Fireworks) and Mozart’s last symphony, the Jupiter. Five days later, in Shanghai, he will lead Haydn’s The Seasons. Where the first concert will be with the Guangzhou Symphony Orchestra, the second, with the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, will also include his Amsterdam Baroque Choir.

Edouard Hamman: Handel (left) and King George I on the River Thames, 17 July 1717

The Beijing and Hong Kong concerts will open with 3 funeral motets by Bach and close with Brahms’ Zigeunerlieder, contrasting the memories of the funeral music with Brahms, whom Koopman considers the most ‘avant-garde’ composer he performs.

Bach: Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied, BWV 225 (Netherlands Chamber Choir; Ton Koopman, cond.)

Since, in both cities, he will be performing with local orchestras and not his own Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, we discussed what he will be requiring from the performers. Performing Baroque music requires a change in aesthetic from the usual symphonic performing techniques: fewer trills, less vibrato, and a more straightforward approach to the music.

He said he was looking forward to his Chinese and Hong Kong concerts not in the least because of the relative youth of the audience. Whereas his audiences in Europe are getting older and concert halls are looking for innovative ways to bring in a younger audience, he’s been pleasantly surprised by the number of young students who attend his Asian concerts.

Christoph Graupner

Aside from his work on the important Baroque composers, Koopman also looks at the ‘minor masters’. Recently, he was looking at the music of Christoph Graupner, who was unable to take an offered position as kantor at the Thomasschule in Leipzig, saw the position offered to Bach. Graupner stayed in Darmstadt and the music history of Leipzig was changed forever. Koopman is also a great advocate of the music of ‘Mr and Mrs Anonymous’ – of which there are metres and metres in many European libraries.

For his own research, the most important thing is to Go To The Library. In an era where everyone believes everything is available online, exploring in a library will take you to places that you don’t expect. You’ll discover new composers, new sources, new opinions, but only if you actually go to the library. He told us of one funny discovery in his own library. He had a book of the works of Handel that he’d casually looked over and was interested in finding more about a name in the book. He consulted the Handel scholar John Roberts in California who asked him to send a few pages of the music. He did so and the reply was completly unexpected: the music was actually an unknown cantata by Handel. The start of the text, Tu fedel? Tu costante? was known, but Koopman’s manuscript included new recitatives and arias that Handel has written in Italy in late 1706. The new cantata, number HWV 171a, was recorded in 2016.

Koopman’s own library is substantial. He estimates he has some 40,000 volumes in his collection. His collection of rare books numbers around 15,000, 85% of which are on or of music before 1800. He is also a collector of engravings, 85% of which are performers, composers, and others associated with music. He also has the ideal support for his library: his own librarian.

Official Website