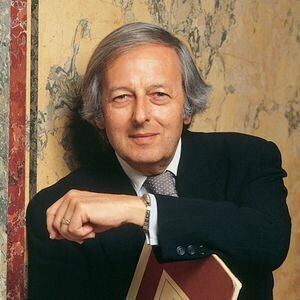

André Previn

Honey and Rue (1992) is a composition for soprano, orchestra, and ‘occasional jazz combo.’ André Previn (b. 1929) is best known for his film work, having won 4 Academy Awards, and for his recordings, winning 10 Grammy Awards, as a pianist, conductor and composer. He was also active as a jazz performer starting in 1945. All of these elements come together in Honey and Rue: there’s jazz writing, filmic writing, and regular symphonic writing. The work is an elegant summation of his entire career.

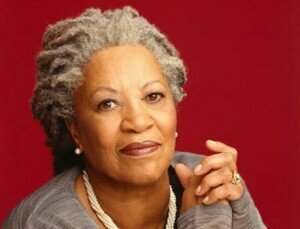

Toni Morrison

Kathleen Battle (b. 1948) is a controversial operatic soprano, with a wide repertoire, but whose reputation for being difficult and demanding. Her unreasonable actions, resulted in her dismissal from the Metropolitan Opera during the rehearsals for 1994 production of La fille du regiment. 22 years later, she returned to the Met for a concert of spirituals in 2016. After 1994, Battle confined her work to recording studios or on the concert stage, but not in full operas.

Kathleen Battle

The orchestral writing comes out in the opening of “First I’ll Try Love,” which is a look back on something unattainable.

Previn: Honey and Rue: No. 1. First I’ll Try Love (Kathleen Battle; Orchestra of St. Lukes; André Previn, cond.)

The second song, “Whose House is This?”, with its hovering strings, depicts the alienation inherent in the African American experience. The musical setting is intensely atmospheric, and the vocal setting slow and deliberate.

Honey and Rue: No. 2. Whose House Is This?

“The Town is Lit” starts in a conversational tone describing a comfortable suburban atmosphere, and the jazz ensemble comes in when we reach the exciting big city – the contrast between the slow and sleepy and the live and exciting is underscored by the change in ensemble.

Honey and Rue: No. 3. The Town Is Lit

The orchestra is silent for “Do You Know Him?”, a soliloquy on God. The voice, first starting in the higher register, is free to range into lower registers, as though to pick up people with the title question before bringing them upward.

Honey and Rue: No. 4. Do You Know Him?

“I Am Not Seaworthy” is a wonderful play on words, and a sad reflection on how an entire class of people were forcibly migrated from Africa to the Americas. The song is about drowning, or the fear of drowning, using a word that is more often applied to the qualities of a boat. The alternation between orchestra sections with the prominent oboe and sections for voice and piano sections highlight the loneliness of the voice.

Honey and Rue: No. 5. I Am Not Seaworthy

The final song, “Take My Mother Home,” opens in the realm of spirituals, with its characteristic flat motions. It moves to a jazz setting, as though moving us forward in the African American experience. The text “Take My Mother Home” brings us to a sound not unlike a television theme. The song expresses a desire for self-sacrifice in the world of slavery.

Honey and Rue: No. 6. Take My Mother Home

The song cycle has a tremendous range of expression and style, and should be far better known than it is today. Kathleen Battle’s performance gives the text an ideal voice – wide ranging and yet intimate.