Danckerts: Ave Maris Stella

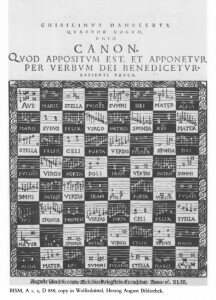

Clearly, this isn’t your normal musical score – it’s been all chopped up into 64 squares like a chessboard.

Let’s start with what’s written at the top. (Ghisilinus Danckerts Quatuor Vocum Unio). This lets us know that we’re looking for a four-voice piece. The rest, Quod appositum est, et apponetur, per verbum dei benedicetur sapienti pauca, tells us that the four voices can be combined. A deeper reading also tells us that the voices should be moving in graphically comparable way, i.e., symmetrically.

Pietro Cerone, the author of the 1613 treatise where this work was preserved, tells us that he tried and tried to solve this riddle of a motet but failed. He was particularly unhappy because in a treatise that Danckerts wrote around 1555, he had said that there were more than 20 solutions to the riddle!

Diagonals

You will also note that many squares have both upper and lower notes – closer examination shows us that this only happens with the squares on a diagonal from the corners. Using chess notation, where the horizontal rows are lettered a-h, and the vertical rows are 1-8, starting the lower left corner, we see that a1, b2, c3, d4, e5, f6, g7, and h8 have the notes for two voices as do h1, g2, f3, e4, d5, c6, b7, a8.

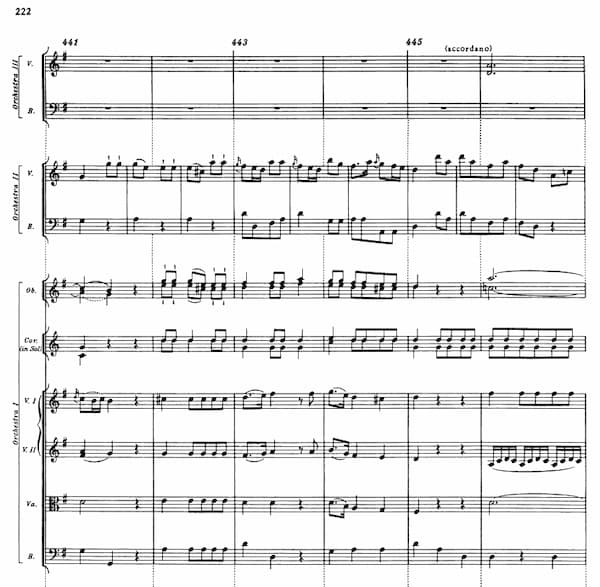

Westgeest’s score for Ave Maris Stella, from Hans Westgeest: Ghiselin Danckerts’ “Ave Maris Stella”: The Riddle Canon Solved, Tijdschrift van de Koninklijke Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis 36 (1986), pp. 66-79.

What about the other 19 pieces? The Dutch musicologist Hans Westgeest solved this in 1986, showing that layout of the words on the chessboard are symmetrical – look, for instance, at the centre, where we have ‘Iram’ at c4 and d5. Using those as a start and, again, moving symmetrically, we can construct the next motet on ‘Iram vertas patris summi,’ another one on ‘Summi dei,’ another on ‘Mater dei,’ and so on. All the motets are made of 16 squares, each using one-quarter of the 64 possible squares.

Unfortunately, there isn’t a recording of Danckert’s puzzling masterpiece, so we’ll leave you with a section of his mass for the Virgin Mary.

Danckerts: Missa de Beata Virgine: Alleluia, Assumpta est Maria