Born in 1897 in Milan, the Italian cellist Enrico Mainardi had a small cello in his hands at the age of three. He astonished everyone by performing one of the Beethoven Cello Sonatas flawlessly just a few years later. Hailed a wunderkind, Mainardi’s father began to send him on concert tours not unlike the grueling schedule of performances Mozart was subject to as a child but he was able to mingle with great artists of the day. One of Mainardi’s recital programs featured none other than the composer Ottorino Respighi at the piano.

Born in 1897 in Milan, the Italian cellist Enrico Mainardi had a small cello in his hands at the age of three. He astonished everyone by performing one of the Beethoven Cello Sonatas flawlessly just a few years later. Hailed a wunderkind, Mainardi’s father began to send him on concert tours not unlike the grueling schedule of performances Mozart was subject to as a child but he was able to mingle with great artists of the day. One of Mainardi’s recital programs featured none other than the composer Ottorino Respighi at the piano.

Mainardi studied at the Giuseppe Verdi Conservatory from 1902-1910, and once he graduated at age 13, he made two important debuts—with the Berlin Philharmonic performing Haydn Concerto, and in London at one of the Promenade programs performing Saint-Saëns Concerto with Sir Henry Wood conducting—an auspicious beginning, which launched Mainardi as a soloist. Nonetheless he continued his studies, joining the class of one of the best teachers in Europe at the time, Hugo Becker.

Haydn: Cello Concerto in D major

One of Mainardi’s most life-changing performances was due to a recommendation from Becker. In 1913, the impresarios of the Bach-Reger Festival in Heidelberg proposed that Becker play Reger’s Fourth Cello Sonata Op. 116, with the composer at the piano. Becker was not eager to learn the work so he suggested Mainardi. The 16-year-old captivated his audience with his gorgeous singing sound, and brilliant rendition of J.S. Bach’s Solo Suite No. 3 in C major, and Reger’s Sonata. The following year Mainardi made his Vienna debut playing Dvořák Cello Concerto.

The First World War interrupted Mainardi’s career. Since he had been on the road as a youngster, and not had a formal education, Mainardi took advantage of the four years to go to school while his cello lay untouched. After the war, when Mainardi was ready to play again, he discovered much to his dismay, his playing had seriously deteriorated. What had happened to his lovely, natural sound? Thinking his playing days might be over, Mainardi enrolled at the Academy of St. Cecilia in Rome to study music composition and piano. But he couldn’t resist the allure of the cello. Mainardi, at the ripe age of 24, returned to Hugo Becker in Berlin to rebuild his technique, improve his cello sound, reclaim ease of playing, and analyze the skills he had previously understood intuitively.

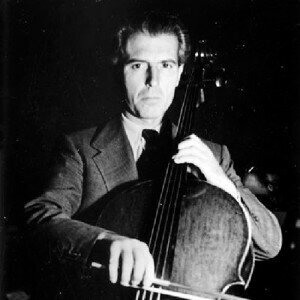

Mainardi became principal cello of the Dresden Philharmonic in 1924 and then the Berlin State Opera in 1929. Three years later he left his position to pursue his solo career. Much in demand, he toured the Soviet Union, he recorded Strauss’ Don Quixote at the composer’s request, with Strauss conducting, he played Brahms Double Concerto often with Wolfgang Schneiderhan, and he premiered both the Pizzetti and Malipiero Cello Concertos.

Mainardi became principal cello of the Dresden Philharmonic in 1924 and then the Berlin State Opera in 1929. Three years later he left his position to pursue his solo career. Much in demand, he toured the Soviet Union, he recorded Strauss’ Don Quixote at the composer’s request, with Strauss conducting, he played Brahms Double Concerto often with Wolfgang Schneiderhan, and he premiered both the Pizzetti and Malipiero Cello Concertos.

Strauss: Don Quixote – Finale

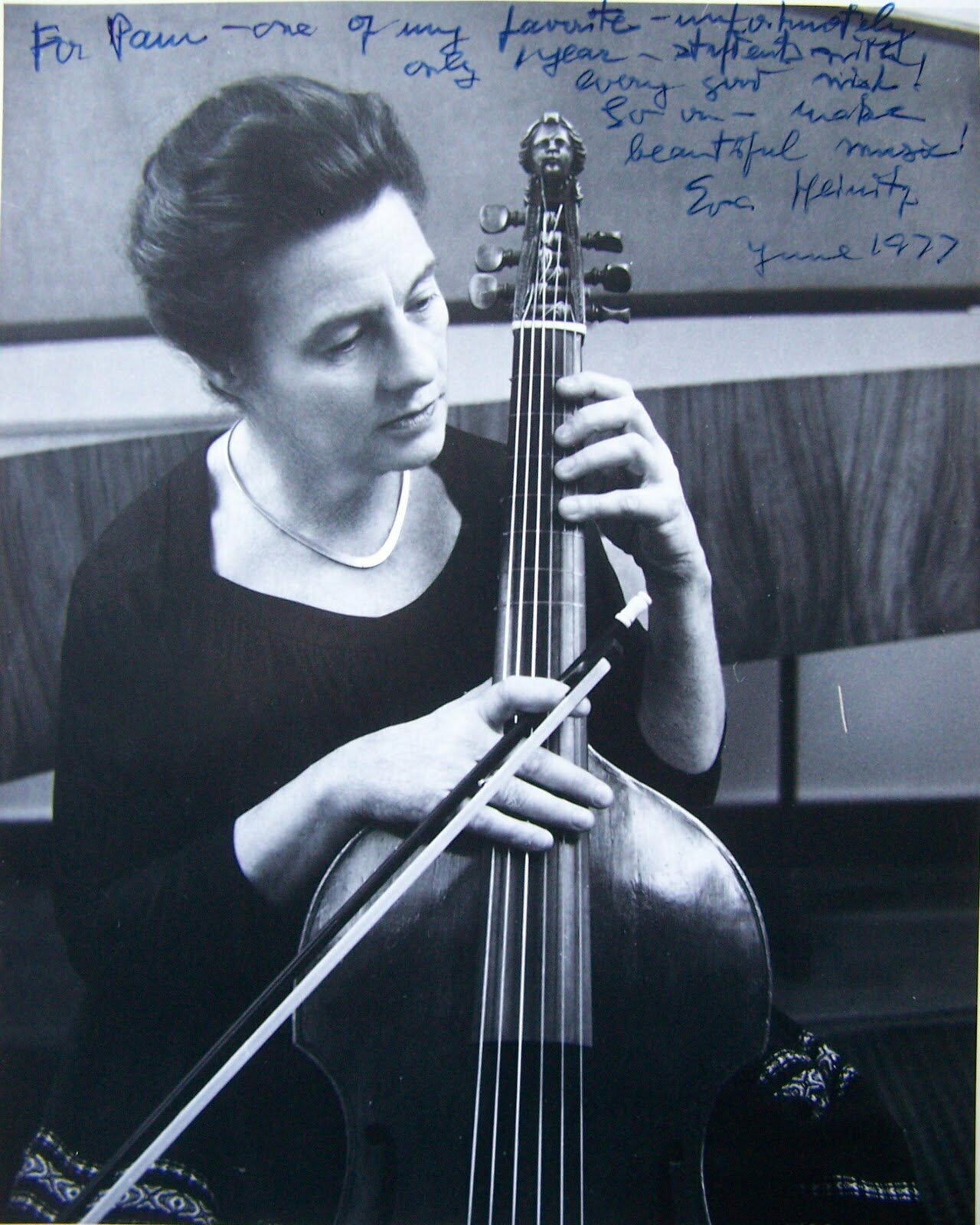

In 1933, Mainardi began what would be a long teaching career, first at the Academia of St. Cecilia and subsequently after Becker passed away, at the Berlin Hochschule. Perhaps due to his own struggles relearning how to coax the finest sounds out of the cello, he was able to recognize and rectify poor technical habits in his students, and he became known as one of the great cello teachers of Europe. A conservative pedagogue, he insisted that students familiarize themselves with the entire score of the music they were playing. In fact, if a student came to a lesson without the full score Mainardi would banish them from the studio. Melodic phrases, he felt, should be governed by the harmonic structure of the music. His many fine students include among others, Miklós Perényi, Siegfied Palm, and Joan Dickson, later a professor at the Royal College of Music, who said, “[he had] a tremendous personality and exuberant vitality, with a wonderful gift for expressing musical ideas in illuminating, if sometimes, ungrammatical language.”

Brahms: Trio (Wolfgang Schneiderhan, Enrico Mainardi, Edwin Fischer, 1954)

Mainardi continued to perform after the Second World War. He was one of the first soloists to program the Bach Solo Suites, sometimes dedicating an entire evening to the works. He formed a piano trio with Edwin Fischer and Wolfgang Schneiderhan, and he appeared with composer and pianist Ernö Dohnányi and Wilhem Backhaus. But his career as a cellist was slow to blossom in France and England. He was much better known as a virtuoso in Germany, Italy, Switzerland, and Scandinavia.

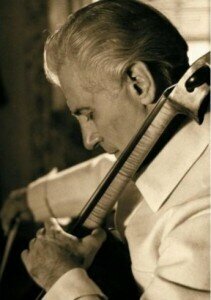

Mainardi had a powerful personality, a flamboyant style, and charismatic good looks. Later in life, notorious for his colorful storytelling, beautifully coiffed white hair, and flowing black cloak, his dramatic gestures and droll humor never intruded upon the music onstage. When performing he was a servant to the composer, “My principle and aim is to be at the service of music and not to use it for the sake of showing myself.” He eschewed showmanship and adopted a more serious demeanor. This approach reminds me of Janos Starker’s onstage persona. Both cellists unjustifiably earned a reputation with audiences of being aloof.

In addition to four cello concertos, Mainardi composed chamber music, solo sonatas, lieder for the baritone Dieter Fischer‐Dieskau and a string concerto for Italy’s Trio d’Arti. He also wrote cadenzas for the major cello concertos, which you can hear in the Haydn D major Cello Concerto. The first movement cadenza is quite virtuosic, and his playing is pristine throughout, the last movement in a lovely lilting tempo, which brings out all the charm of the piece.

Mainardi is certainly a cellist to remember. He died in 1976.

Franz Schubert: Sonata D 821 “Arpeggione”per cello e pf. Enrico Mainardi – Carlo Zecchi