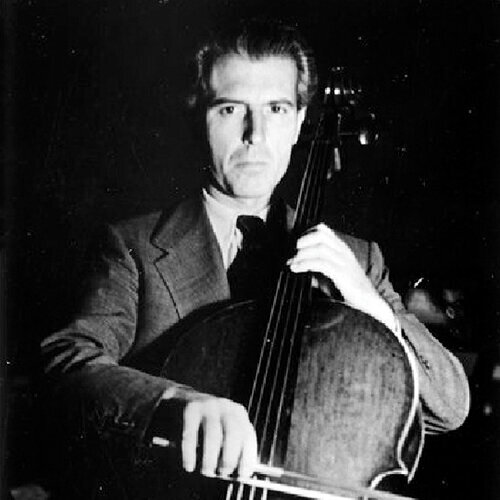

Bernard Greenhouse

Beaux Arts Trio – Schubert: Piano Trio in B flat

Born in New Jersey in 1916, Greenhouse, the youngest of four brothers, who played the piano, violin, and flute respectively, was handed a cello at age nine. He studied with the crème de la crème—four teachers with varied approaches, who each made a significant contribution to Greenhouse’s playing. Focused studies began with Felix Salmond at the Juilliard school. No doubt Salmond’s breathtaking sound influenced the young cello student, who concentrated on his right-hand technique, in order to produce a beautiful tone quality. But his left-hand skills were imperfect, even clumsy. Greenhouse found Emanuel Feuermann’s left-hand facility awe-inspiring, and during two years of intense lessons he sought to emulate Feuermann’s natural ease of expression. Tragically, Feuermann died in 1942. With the advent of the US involvement in the Second World War, Greenhouse joined the US Navy. During that time, he took lessons from Diran Alexanian with whom he had constant musical debates. “I was enormously impressed with his musical ideas. He was a musical genius and pedagogue, not a great cellist.” Alexanian coached Greenhouse for his 1946 New York recitals, but Alexanian would not take payment for cello lessons. Fortunately, Alexanian’s weakness for gastronomical pleasures resulted in a cross-country tour of France’s greatest restaurants—fitting compensation for Alexanian.

After two previously unsuccessful attempts to study with Pablo Casals, Greenhouse was accepted as the only student of the great man. At the time, not yet dedicated to teaching, Casals agreed to hear Greenhouse, providing he donate $100 to the Spanish refugee Fund. Two years of lessons ensued—often 4-hour marathons, several times a week. A great deal of time was spent conversing about the art of music-making. Greenhouse shared the essence of Casals’ approach in The Great Cellists by Margaret Campbell. He recalled a lesson. Casals asked Greenhouse to learn the Bach D Minor Cello Suite from memory in three weeks, with specific bowings, fingerings, phrasings, tone colors, and dynamics. Greenhouse dedicated himself to the task, even matching the exact vibrato of the master. After performing the work flawlessly in his lesson, Casals switched gears and asked Greenhouse to change everything—the bowing, phrasing, dynamics, and fingerings. “I was astonished” said Greenhouse, “that this man could remember for weeks what he had told me, play it, and then change everything in order to show that playing a Bach Suite was a creative process. It didn’t apply only to Bach— but to everything I played…I should never make up my mind that there was an absolute way to play a phrase…to set my mind so finally I would lose the feeling of inspiration…”

After two previously unsuccessful attempts to study with Pablo Casals, Greenhouse was accepted as the only student of the great man. At the time, not yet dedicated to teaching, Casals agreed to hear Greenhouse, providing he donate $100 to the Spanish refugee Fund. Two years of lessons ensued—often 4-hour marathons, several times a week. A great deal of time was spent conversing about the art of music-making. Greenhouse shared the essence of Casals’ approach in The Great Cellists by Margaret Campbell. He recalled a lesson. Casals asked Greenhouse to learn the Bach D Minor Cello Suite from memory in three weeks, with specific bowings, fingerings, phrasings, tone colors, and dynamics. Greenhouse dedicated himself to the task, even matching the exact vibrato of the master. After performing the work flawlessly in his lesson, Casals switched gears and asked Greenhouse to change everything—the bowing, phrasing, dynamics, and fingerings. “I was astonished” said Greenhouse, “that this man could remember for weeks what he had told me, play it, and then change everything in order to show that playing a Bach Suite was a creative process. It didn’t apply only to Bach— but to everything I played…I should never make up my mind that there was an absolute way to play a phrase…to set my mind so finally I would lose the feeling of inspiration…”

Casals explored the link between language and musical expression. Just as speech conveys emotion, in music, a phrase must ‘speak’ to evoke meaning. Greenhouse embraced this idea and later encouraged his own students to imitate the inflections and rhythms of language as a model for articulation in music.

Carter E.: Cello Sonata – Adagio

Beaux Arts Trio

Ravel: Piano Trio – I modere

A chance encounter in 1955 at Tanglewood—the summer home of the Boston Symphony—with violinist, Daniel Guilet and pianist, Menahem Pressler, led to a few trio performances. The string quartet with its extensive repertoire captivated audiences but who could make a living playing in a Piano Trio? The Beaux Arts Trio concerts became so successful, they were asked to tour. Celebrated, in demand all over the globe, they became known for their luminous interpretations of the trio literature, which is almost ‘symphonic’ in scope. Recordings followed and included Beethoven’s Triple Concerto in C major, which was a signature piece in their repertoire, played with ensemble that is rarely achieved by three soloists who come together just to perform this work.

Beethoven: Triple Concerto – Allegro

Retiring from the trio in 1987 after 32 years with the group, he continued his busy teaching schedule at the Juilliard and Manhattan Schools of Music and Stony Brook University.

Greenhouse played on perhaps the most magnificent Stradivarius cello in existence, ‘The Countess of Stanlein, ex-Paganini, from 1707’ his constant companion for 54 years, which had been meticulously restored. And in the safe with the cherished Stradivarius: a packet of all the letters Greenhouse ever received from Casals.

When the trio travelled by air, the three members split the cost of an airline seat for the valuable instrument. Today we cellists moan about having to pay for a full fare ticket with no guarantees that we will even be allowed onto the plane. Margalit Fox of the New York Times relates a memorable story in Mr. Greenhouse’s obituary, “Years ago, in less rapacious times, cellos could fly half-price, on a child’s ticket. Once, at an airport check-in counter, an agent, reading the name on just such a ticket, asked, “And how old is your son, Cello, Mr. Greenhouse?” “Two hundred fifty years,” Mr. Greenhouse replied promptly, before collecting his son’s boarding pass and lugging him to the gate.

Bernard Greenhouse passed away in 2011 at the age of 95. The following year the Greenhouse Stradivarius was bought by a Montreal arts patron for an amount in excess of six-million dollars. The Boston-based dealer who handled the sale said the new owner would loan the cello to the then 18-year-old Canadian cellist, Stéphane Tétreault, who was studying at the University of Montreal with Yuli Turovsky. I interviewed the young cellist in 2014. Today his career is flourishing no doubt inspired by the beautiful sounds Greenhouse made on the instrument.

Bernard Greenhouse on the Language of Emotion through Music with Paul Katz