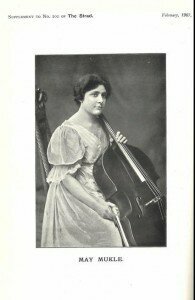

Portrait of May Mukle. By John Mansfield Crealock.

Oil on canvas, 1930.

Born in 1880, into a musical family, and exceptionally gifted, May was performing by age nine, and supporting herself by age eleven. She whizzed through the Royal Academy of Music and began to tour as a teenager—throughout England, Europe, Australia, USA, and even Asia and Africa, earning herself the moniker, “the female Casals.” Imagine what it must have been like to travel with a cello in those days!

Adolphe Fischer: By the Brook – May Mukle, cello, George Falkenstein, piano

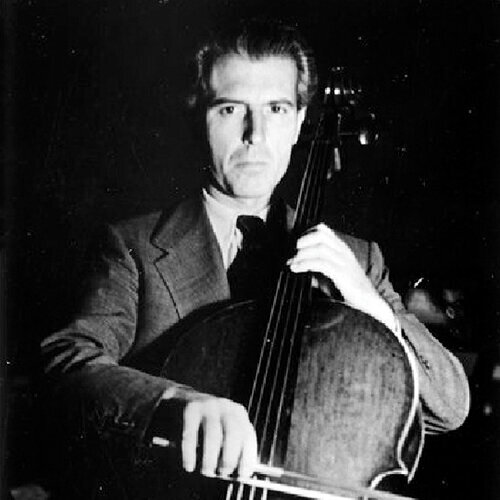

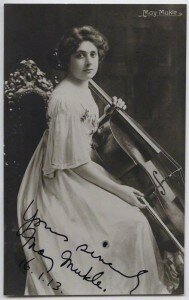

May Henrietta Mukle, by Unknown photographer, 1900-1913 – NPG x21440 – © National Portrait Gallery, London

Holst: Invocation Op. 19, No 2 with Raphael Wallfisch as cello solo

Mukle was equally dedicated to chamber music and joined such great artists as violinist Jacques Thibaud, violist Lionel Tertis, and pianist Arthur Rubinstein. Many of these programs were private concerts in salons of well-known patrons. Arthur Rubinstein remembers a performance of the Brahms string sextets and May’s “beautiful playing” with Thibaud, and Paul Kochanski on violins, Tertis and the conductor Pierre Monteux on viola. The two cellists were May and Felix Salmond.

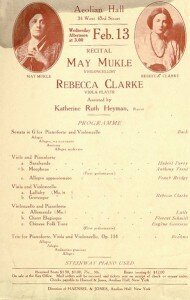

Aeolian Hall program, Feb 13, 1918

The Maud Powell Trio with Mukle’s sister Anne on the piano, garnered tremendous acclaim during their tours of South Africa, and the US. Appearing in New York at the New German Theater in 1908, a New York Times review indicated that the hall was “well-filled” and they were “warmly applauded.” They featured a woman composer, another rarity for the time—Cécile Chaminade. Born in Paris in 1857, her expressive and poetic Trio in A minor is rarely played even today. On their programs were trios by Beethoven, Eduard Schütt and Anton Arensky.

I wish we could have heard one of her inventive recital programs. She appeared at Aeolian Hall in New York City in 1918 with violist and composer Rebecca Clarke, and performed compositions of Hubert Parry, Frank Bridge and the premier of Clarke’s Morpheus. One can understand why Clarke used a pen-name: Anthony Trent—his works received more applause than Clarke’s. A performance in 1924 at the Memorial Church in Stanford, Connecticut advertised her concert with organ—Sonata in G minor by Henry Eccles, Bois Epais by Jean-Baptiste Lully, Après un rêve by Gabriel Fauré, Bach’s Solo Cello Suite in C, Sketch in F minor by Schumann, and MacDowell, (arranged by Mukle), Purcell and Geminiani.

“Miss Mukle’s tone is of a rare beauty and searching power; her playing has dignity, repose, a penetrating musical quality; an unfailing intonation is one of its merits,” wrote The New York Times.

Mukle was fortunate that an anonymous collector and admirer offered to purchase a rare cello for her: a Montagnana, coveted by cellists even today. The Italian master luthier (1686 –1750) made beautiful sounding cellos. Mukle seemed to have no difficulty navigating the instrument, which tend to be larger sized. Generously, she loaned her cello to gifted young cellists for important debuts.

Mukle was fortunate that an anonymous collector and admirer offered to purchase a rare cello for her: a Montagnana, coveted by cellists even today. The Italian master luthier (1686 –1750) made beautiful sounding cellos. Mukle seemed to have no difficulty navigating the instrument, which tend to be larger sized. Generously, she loaned her cello to gifted young cellists for important debuts. A vivacious, and engaging person, her apartment became the meeting place for visiting artists. On any given day, she would be entertaining Vaughan Williams, John Ireland, Ravel, or Casals, a close friend, who greatly admired Mukle’s playing. And due to her efforts, her building, originally a four-level office building near London’s Wigmore Hall—was converted to individual apartments and soon filled with musicians, who could make music to their heart’s content without disturbing the neighbors!

According to Margaret Campbell, in The Great Cellists, May also founded the Mainly Musicians Club “in a converted basement adjacent to Oxford Circus Tube Station, as a meeting place and restaurant.” During World War II, May manned the club, tin helmet donned, when the underground location was converted to an air raid shelter.

After the war, despite being in her seventies, she travelled to Africa to concertize. Seriously hurt in a car accident while there, her injuries stopped her only temporarily. Mukle made a painful comeback and toured the US in 1959, a mere three years before she passed away at age 82.

Her obituary in The London Times says: “by the turn of the century she was fully recognized not only as an outstanding musician but as one of the most remarkable cellists this country had produced.” A beautiful portrait, painted in 1930 by John Mansfield Crealock, hangs in the museum of the Royal Academy of Music, and since 1964 a prize in Mukle’s honor has been awarded to cello students of the college.

Alice Bredt Verne: Lullaby – May Mukle, cello, George Falkenstein, piano