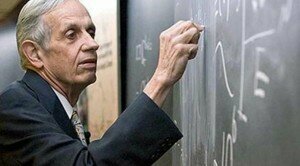

John Nash

Nash won his Nobel Prize for conceiving the “The Nash Equilibrium” which spawned Game Theory. The Nash Equilibrium is the same as the MiniMax theorum in game theory, which states that “with a zero-sum game, each player does best for himself by minimizing the other player’s payoff”

The easiest example to understand is the pie game. It’s a game of 2 players who can share a pie if they follow 2 rules:

1. One player cuts the pie any way they want

2. The other player has the first choice of slices

The winning strategy for Player 1 is to cut the pie exactly in half. Player 1 maximized the minimum size of the piece of pie that would be left after Player 2 chose.

Sadie Harrison : Impresa Amorosa – VII Candle

Can game theory explain why new composers find it so difficult to break into mainstream concert programmes?

Here’s how the MiniMax Theorum might be applied to concert going: the concertgoer has a choice between a recital of familiar works by Bach, for example, or a recital of unfamiliar contemporary music. MiniMax Theorum states that choice is made by minimizing the maximum regret and suggests that the concertgoer’s winning strategy is to choose the Bach recital since he/she knows they won’t regret hearing Bach but could regret hearing the new music. So it doesn’t matter how good the new music might be, mathematically the optimum choice is Bach!

Unfortunately, the concertgoer’s choice is further determined by the paucity of new music in mainstream concert programmes. It comes back to the argument that if we are not exposed to new music, how can we decide if we like it?

Cheryl Frances-Hoad: Contemplation

For promoters, agents and venue managers, a rather more straightforward strategy is at work: that it is simply too risky to programme new music when a concert featuring familiar works by Bach is likely to ensure a full house, a contented audience and decent revenue from ticket sales.

With the odds apparently stacked against it, how can new music be brought to a wider audience? Often just seeing the words “new commission” or “premiere” in the advertising for a concert can put people off, such is the common misconception that most “new music” is atonal, discordant, impenetrable or highly esoteric, and that they probably won’t like or understand it. Convincing potential audiences that they might actually enjoy new music can be tricky with so many, often negative, pre-conceived notions surrounding it, but clever advertising and programming can tempt people to sample new music, perhaps by placing it in a programme with more familiar works, or with repertoire which may have inspired the composer, thus allowing the familiar to illuminate or make connections with the new. Another effective way to attract potential audiences is via social media: “teaser” tweets and imaginative posts containing audio or video samples, an interview with the composer and/or performer/s or an introduction to the programme can tempt audiences to try a concert featuring new music, and the promoter/concert organiser can reassure the prospective concertgoer that this may well be music that they will enjoy. We talk a lot these days about “accessibility” in classical music – making the concert experience more welcoming and open to all, and this must include helping existing and potential audiences to engage with new music.

Meredith Monk: Ellis Island