Razzac cello © Anis Heydari CBC

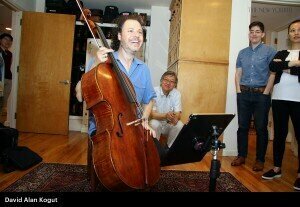

Cellist Matt Haimovitz recently had such a decision to make. He was teaching a lesson, and a bit clumsily stood up to reach for the music to Francis Poulenc’s Sonata. He stumbled. Mid-air he contemplated falling on top of his valuable 1710 Matteo Goffriller cello, his companion for thirty years, or letting it go, come what may. He released the cello, the sound of splintering wood like a knife thrust into his own chest.

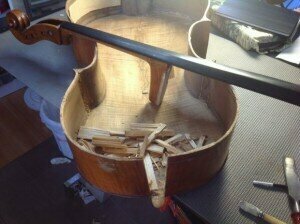

Once the team of luthiers at Reed Yeboah Fine Violins in New York had a look they had to do the unthinkable. They took the top off, and disassembled the exquisite cello. Matt couldn’t watch. It felt like a dismemberment. Certain things start happening when you’re 300 years old: cracks reopened, the top caved dangerously inward, and the soul of the cello, the soundpost—a little wooden dowel that conducts the sound from the top to the back—had to come down. It would take months to repair.

Matt Haimovitz © David Alan Kogut / The New Yorker

Philip Glass: Crypt Session (Matt Haimovitz)

Tariq Abdul Razzac, a resident of Calgary, has a hair-raising story. His cello saved his life. A member of the Iraqi National Symphony Orchestra in Baghdad, he had the audacity not only to play a concert but to perform at the U.S. Embassy in Bagdad. Which was the greater crime—playing music or collaborating with the west? As Razzac left the concert, with the cello in its forest green case strapped on his back, Iraqi militants began shooting at him. The whizzing bullets punctured the case virtually shattering the cello but Razzac was safe. Over the ensuing months Razzac made several futile attempts to repair the instrument himself using wood scraps to patch the broken pieces. The wreckage sat in the bullet-ridden cello case for three years.

Roman Totenberg

Interview of Razzac

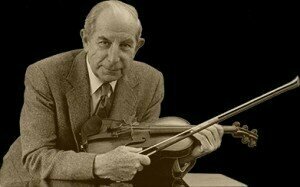

Violins also need to go to the specialists from time to time. A remarkable instrument was recently restored—The Ames-Totenberg 1734 Stradivarius violin. Roman Totenberg , a fantastic violinist and pedagogue, performed on this instrument for 38 years. Then tragedy struck. While Totenberg was greeting audience members after a concert at the Longy School in Massachusetts, the violin was stolen from his office. He never saw it again. Phillip Johnson a young, second-rate violinist who hung around that day, was suspected of taking the violin but there was no proof. He eventually moved across the country. Four years after Johnson died in 2011, his widow found the violin locked in a case. After breaking the latches, she was astonished to see a Stradivarius label. Experts, were skeptical. Who doesn’t think granny’s old instrument in the attic is a Strad? They arranged a meeting, identified the violin as the missing instrument, and summoned the police—but too late for Totenberg. He had passed away at the age of 101 in 2012.

Nathan Meltzer

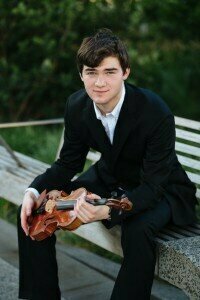

The instrument would have been recognized if Johnson dared take it out of his apartment, so for 35 years the violin didn’t have even a routine physical. Rare Violins of New York completed the two-year painstaking restoration. The Totenberg sisters knew their father would have wanted the violin to be in the hands of a virtuoso player, heard by audiences everywhere, and not relegated to a collector’s glass case. As luck would have it, an anonymous benefactor purchased the violin, with the stipulation that the Strad would be loaned to a deserving young virtuoso, overseen by the newly formed Rare Violins In Consortium Artists & Benefactors Collaborative.

The first recipient, a student of Itzhak Perlman, has already performed the world over. Eighteen-year-old Nathan Meltzer, is up to the challenge.

Saint Saens: Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso (Nathan Meltzer)