Amnon Weinstein

Instruments in the trenches, played by soldiers and for soldiers, sometimes made of odd bits of paraphernalia relieved the stress of battle. In the worst of circumstances making music has elicited hope.

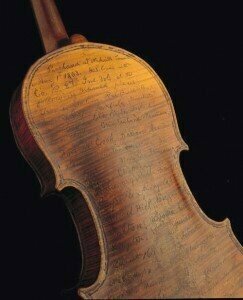

During the Civil War, haunting fiddle music rose out of a violin, a violin which performed double duty. Owned by Solomon Conn, an Infantryman, Conn hand-wrote accounts of battles and their locations, but instead of using a paper diary, he inscribed the violin with his experiences. Both violin and owner survived the war. Bequeathed to the National Museum of American History after Conn’s death in 1926, it’s a stunning and historic document of the time.

Bridge: Cello Sonata

Parry: Jerusalem

Novello: Keep the Home Fires Burning

Civil War violin used as war diary by Civil War soldier Solomon Conn 1863 © History Lovers Club

Stven Isserlis with the Trench cello to Jens Braun

© The Guardian

Instruments with tragic associations to the Holocaust were used for more sinister purposes and hold haunting secrets. In the 1940s enslaved Jewish musicians performed in the concentration camps and ghettos, even in Auschwitz death camp, in small ensembles, orchestras, and as soloists. Inmates were forced to play while their fellow prisoners trudged to and from slave labor, and at the doors of the crematoriums when captives took their final steps to the gas chambers. Often, the ability to play an instrument saved the owner’s life.

Music was performed for the entertainment of Nazi guards and music offered comfort and elicited courage in the prisoners. Several violins, which were played during the Holocaust, were recovered and brought to the attention of world-renown Israeli luthier Amnon Weinstein, whose own family lost hundreds of relatives during the Holocaust. He has dedicated his life to restoring these instruments. Conveyed in the book Violins of the Holocaust-Instruments of Hope and Liberation in Mankind’s Darkest Hour by James A. Grymes, each violin tells an incredible story.

Playing on one of these violins is deeply moving. Although the owners are gone, we hear their voices resonate. The violins personify and bear witness to one of the darkest times in history. Sharing the stories of horror and of human resilience with future generations is of utmost urgency.

Amnon “A voice from another world”

Amnon Weinstein and violinist Shlomo Minz have co-founded The Violins of Hope project to promote peace through music. The Violins of Hope project encourages community-wide collaboration between musicians and audience, educators and students, and through exhibits and artifacts. One of the concerts, with the Cleveland Orchestra and soloist Shlomo Mintz, was filmed in its entirety in 2015. The impact of the arts cannot be underestimated. These instruments are a testimony to our human need for beauty and solace.

Today the Violins of Hope tour the world and are showcased in performances to honor the musicians who perished. Next February 23, and 24, 2019, the violins travel to Phoenix, Arizona. Under the auspices of Arizona Musicfest, The Festival Orchestra will perform Beethoven’s Leonore Overture, from the opera Fidelio, which addresses freedom from oppression; Mahler’s Totenfeier, John William’s Theme from Schindler’s List, Allan Naplan’s Schlof Main Kind, a Yiddish Lullaby and will feature violin soloist Gil Shaham in the Brahms Violin Concerto.

Today the Violins of Hope tour the world and are showcased in performances to honor the musicians who perished. Next February 23, and 24, 2019, the violins travel to Phoenix, Arizona. Under the auspices of Arizona Musicfest, The Festival Orchestra will perform Beethoven’s Leonore Overture, from the opera Fidelio, which addresses freedom from oppression; Mahler’s Totenfeier, John William’s Theme from Schindler’s List, Allan Naplan’s Schlof Main Kind, a Yiddish Lullaby and will feature violin soloist Gil Shaham in the Brahms Violin Concerto.

There will be a third concert, a chamber music concert, in tribute to the legacy of Holocaust musicians through music and stories. I am honored to be one of six performers who will play and speak on this program. My father—a fine cellist and member of the Budapest Symphony before the war—survived slave labor in the copper mines of Bor Yugoslavia. Between 1946 and 1948, after wheeling and dealing on the black market to procure a cello, he and 16 other survivors performed in displaced personas camps all over Bavaria—stirring spirits, bringing hope to those barely alive, who had lost family, friends, and their identities. The chamber music performance in Arizona is on February 26th, which would have been my father’s 97th birthday.

Amnon will oversee the violins as they travel to Phoenix, Arizona. The instruments have to be carefully packed into special cargo containers, shipped on a cargo plane, then trucked to the venues. Amnon is there in person to receive the instruments, where he carefully unwraps and inspects each instrument when they arrive. To date, Amnon Weinstein has restored 65 instruments. Rumor has it, that there is now at least one cello in the collection. I am hoping to play it.

Cleveland Orchestra 2015 Violins of Hope