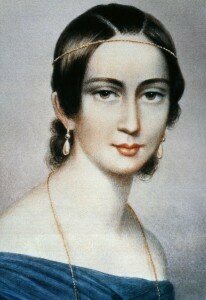

Clara Schumann

Robert Schumann writing to Clara Wieck, March 1838

Never one for disguising his emotions, Robert Schumann wore his heart on his sleeve and his music reflects his joy at being alive – and of being in love. His Fantasie in C, composed in 1836, is a remarkable display of soul-bearing, a piece imbued with passionate and unresolved longing, and the heart-fluttering panoply of emotions from ecstasy to agony which being in love provokes. It was written during a particularly long separation from his beloved Clara Wieck, at a time when their future together was far from certain.

The Fantasie in C is a love letter in music, a culmination of passion, virtuosity and delicacy. No salon sweetmeat, this is a highly demanding, sweepingly romantic large-scale work which pianists approach with trepidation.

Originally intended as a tribute to Beethoven and eventually dedicated to Franz Liszt, the Fantasie is cast in three movements. It alludes to sonata form but like its dedicatee’s B-minor Sonata, Schumann dissolves the formal structure to create a work of striking improvisatory freedom which heightens its emotional impact and poetic narrative. The ‘Clara theme’ which pervades the work is heard immediately in the descending octaves of the right hand. The music is an intriguing mix of grandeur and intimacy: the opening statement, a rolling dominant 9th chord, expresses the full depth of the composer’s passion and the music moves from a state of yearning to one of subdued tenderness before the restatement of the opening. The Adagio coda begins with a secret love message to Clara: a phrase quoted from the last song in Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte: “Take, then, these songs, beloved, which I have sung for you.”

Robert Schumann

Sublimely beautiful, tender and intimate, the third movement is an extended song without words, with ravishing diversions into the remote keys of A-flat and D-flat major which create an extraordinary sense of time suspended. In this movement the passion may be downplayed but it is no less powerfully felt. Falling motifs (drawn from the slow movement of Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ Concerto, and melodies of intense poignancy give way to a section of delicate tenderness, a waltz in all but name with 2 voices – treble and bass – singing together. One can almost picture Robert and Clara clasped in a deep embrace. The coda is an ecstatic declaration, gradually increasing in speed, before pulling back to Adagio for the close and three hushed C-major chords which are at once peaceful and yet tinged with sadness.