One of my favorite pieces to perform is Hungarian composer Béla Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances. It is full of infectious rhythms, melancholy melodies, and subtle effects. János Starker performs it in the cello rendition.

Notice the strong dance-like accents on the first beat of the bar—which Starker used to say comes from the Hungarian language. The accent falls on the first syllable of every word, and listen for the effects—whistling sounds, a mixture of harmonics and playing on the bridge (ponticello) and the use of pizzicato.

The wistful, languid, and harmonically rich pieces Hungarian Peasant Songs are popular with pianists.

Bartók: 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs, BB 79

And violinists love the 44 Duos for two violins. Some are only seconds long. Here are four played by two of my favorite violinists Itzhak Perlman and Pinchas Zuckerman.

Bartók: No. 35. Ruten kolomejka (Ruthenian kolomejka)

Bartók: No. 26. Ugyan edes komamasszony… (Teasing song)

Bartók: No. 32. Maramarosi tanc (Dance from Maramaros)

Bartók: No. 11. Gyermekrengeteskor (Lullaby)

© The Telegraph, Oct 2013

Do I have an ulterior motive for showing you these lovely works? Yes, because I don’t understand why audiences shy away from Bartók’s music. Perhaps it’s because they don’t understand his particular musical language. Considered one of the most important composers of the twentieth century, Béla Bartók, still, it seems to me, inspires fear in audiences. I love his music and not only because I am of Hungarian heritage. I find his music always fascinating, and challenging to play.

Born in 1881, Bartók was precocious, and by the age of four he could perform several piano works. He played one of his own pieces at his first public recital at the age of eleven. Like many other great Hungarian artists, he studied at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest and there met Zoltán Kodály. They became lifelong friends and together began to explore the folk music of their country.

Hungarian composer and pianist Béla Bartók listens to folk music on a phonograph with villagers, 1907.

© Hulton archive, Gabriel Hackett

Once he became piano professor at the Academy he was able to remain in Hungary and travel into the countryside with primitive recording equipment to discover and preserve Magyar songs. The music had been passed on by aural tradition and not written down until then. Bartók found it remarkable that the folk tunes were usually based on the pentatonic scale, like the music of central Asia, with irregular rhythms from traditional village dances. Listen to the stomping of these dancer’s feet!

Both Bartók and Kodály incorporated and adapted this authentic music into their own compositions. They published the 1906 Hungarian Folk Songs for Voice and Piano, a volume of the songs they had collected—in essence, founding the field of ethnomusicology. Later, Bartok’s fascination expanded and he published more editions, exploring the folk music of Romania, Bulgaria and Transylvania, and the music of North Africa and Turkey. In all, he assembled more than 9,000 Magyar, Slovák, Romanian, Serbian, and Transylvanian folk songs, 200 Arab tunes, and edited 16,000 songs.

Bartók had found his musical language. Initially, some of his music was met with hostility—his only opera, Bluebeard’s Castle composed in 1911, reflected the disquiet of Europe approaching war. It is a one-act opera lasting about an hour, and only has two characters, but the theme ranks among the more gruesome tales, something like a contemporary horror movie. Performing it is daunting because it is in Hungarian—a very difficult language for foreigners to learn. When Bartók wrote the ballet the Wooden Prince, a fairy tale and a much more congenial work, the two were programmed together, allowing the darker psychodramatic Bluebeard an opportunity to be heard.

As Bartók’s fame as a soloist and composer increased, his subsequent works such as the Dance Suite for Orchestra 1921, Divertimento for Strings 1923, and Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta from 1936—another of his best-known pieces— become increasingly complex rhythmically, and harmonically.

Bartók: Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, BB 114 – IV. Allegro molto

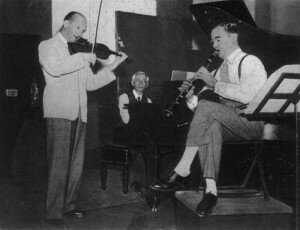

Béla Bartók with Benny Goodman, 1940 recording session

Bartók: String Quartet No. 2, Op. 17, BB 75 – II. Allegro molto capriccioso

Bartók: String Quartet No. 4, BB 95 – IV. Allegretto pizzicato

He wrote other chamber music including his Contrasts for piano, violin and clarinet. Here is the Recruiting Dance from a famous recording with Hungarians, violinist Josef Szigeti and Géza Anda, pianist, with ‘King of Swing’ Benny Goodman on clarinet.

Bartók: Contrasts, BB 116 – I. Verbunkos (Recruiting Dance)

I love to play the ballet Miraculous Mandarin. Depicting the chaos of modern life, it was actually banned due to sexually explicit content. A girl is seen from an upstairs window dancing seductively, depicted by the clarinet, in order to lure men up to the apartment to rob them. Her accomplices are foiled when the third, an affluent Chinese man, a Mandarin, is enticed upstairs. There’s a desperate pursuit. The tramps cannot kill the Mandarin, not until the girl submits and his lust is satisfied. The music returns to erotic waltz-like strings. The final chase scene 16 minutes 45 seconds in, is primitive, ferocious, and demanding music to play.

Bartók was dedicated to educating young players and wrote several volumes of lovely piano pieces For Children.

Bartók: For Children, BB 53, Vol. 1 (based on Hungarian folk tunes) – No. 1. Children at Play (Allegro)

A staunch Hungarian, he became alarmed at the alliance between Hungary and Germany in the 1930s. When the Second World War broke out Bartók’s position became unbearable. Despite his misgivings he emigrated to the United States in 1942. Although he did obtain a position at Columbia University, his engagements dried up. He lived in relative obscurity and poverty as his health began to fail. Fortunately for the world of music, the conductor Serge Koussevitzky commissioned Bartók to write his Concerto for Orchestra in 1943. Before he died in 1945 at the age of 64, he was able to nearly complete his third piano concerto, a wonderful piece, and sketch out a viola concerto.

Still afraid of Béla Bartók? I hope not!