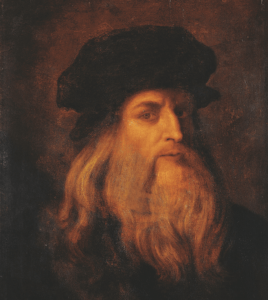

What is there to say about Leonardo da Vinci that hasn’t been said over the last 500 years? Well, let’s start with some superlatives before placing the man within the context of the Italian Renaissance.

Leonardo da Vinci

Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci

Growing up in the city of Florence and spending much of his professional life in Milan, Leonardo was part of an electric artistic environment permeated by a wealth of sacred and secular music. Music was everywhere, as it was an integral part of court and church activities, not to mention civic festivities and theatrical performances. We know little about Leonardo’s musical education during his early years in Florence, but by 1472 he was accepted into the artists’ guild in Florence and became familiar with the craft of music. The city of Florence was ruled by Lorenzo de’ Medici, the most powerful and enthusiastic patron of Renaissance culture, who employed among others Botticelli and subsequently Michelangelo. At the age of 31, Leonardo left Florence and entered into the services of the Duke of Milan. Milan was politically and militarily ambitious, and arts played a subsidiary role. And while Leonardo undoubtedly relished his engagement with military and civic engineering projects, he surely must have missed the intensity of the Florentine humanist tradition.

lira da braccio

Leonardo lived in Milan from 1483 to 1499, and then again from 1506 until his departure for Rome. His time in Milan overlapped with the tenure of Franchinus Gaffurius, one of the most significant Italian music theorists and composers of the Renaissance. Leonardo and Gaffurius knew each other for twenty-two years, and they exchanged books on various topics. Although controversial among modern art historians, the male portrait “The musician,” was possibly painted by Leonardo and might actually depict Gaffurius. Leonardo also rubbed shoulders with Lorenzo da Pavia, an outstanding maker of musical instruments that were prized throughout the Italian peninsular. And let’s not forget that he made friends with a mathematician of international fame, Luca Pacioli. In 1499, after the occupation of Milan by the French army, Leonardo and Pacioli left Milan for Venice. Pacioli published a famous three-volume treatise on proportions in the sciences and arts, and Leonardo contributed sixty drawings.

Portrait of Franchinus Gaffurius by

Leonardo da Vinci

By 1502, Cesare Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI, employed Leonardo as a military architect and engineer. Leonardo briefly returned to the city of his birth in 1503 to design and paint a mural of “The Battle of Anghiari,” and by 1506 he was reunited with his most prominent pupils and followers in Milan. When Pope Leo X employed him from 1513-1516, he essentially became a colleague of both Raphael and Michelangelo. As you might know, Leonardo did not get along with Michelangelo at all, but they could never deny their respective influences on each other. Leonardo spent the last three years of his life in the services of King Francis I of France, residing in the manor house Clos Lucé near the king’s residence at the royal Château d’Amboise. He died on 2 May 1519 at the age of 67. Apparently, Leonardo uttered on his deathbed, “I have offended against God and men by failing to practice his art as I should have done.” Leonardo was brilliant beyond description! However, this exceptional scientist, experimenter, pioneer in acoustics, and inventor of new and fantastic instruments lived in an environment that was inhabited by countless individuals just as brilliant as himself. Born into one of the most fertile and creative periods of human history, only in the Italian Renaissance could a genius like Leonardo have flourished the way he did.