Politicians in particular talk a lot about the “weight of history” or of feeling “the hand of history on our shoulders”, especially when faced with a serious national crisis or significant policy decision.

As musicians we feel the weight of history too – through the many exceptional musicians who have gone before us and the fine recordings of the “great works” of the repertoire which serve as benchmarks or models for our own progress. These can affect our approach to our music making and influence the way music is presented to others.

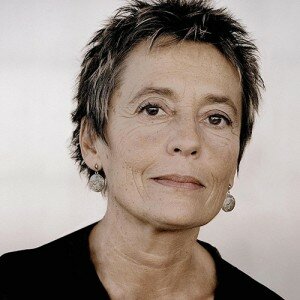

Whether or not you like his playing, the presence of Glenn Gould hangs heavily over anyone playing Bach, and his two recordings of the Goldberg Variations, a great work in itself, are held up by many as the absolute zenith of greatness in this repertoire. Similarly, Andras Schiff and Angela Hewitt, both fine Bach interpreters, also cast a significant shadow over those of us who choose to play Bach’s music. In Mozart we have Mitsuko Uchida and Maria João Pires , Barenboim in Beethoven, Lupu in Schubert, Pollini in Chopin, Argerich in, well, virtually anything, and Perahia for “all round excellence”….the list is endless as everyone has their personal favourites, and each era seems to bring yet another crop of “greats”.

Maria João Pires

The classical musician’s training is still largely about preserving tradition and the reverential “canonization” of repertoire: we’re taught from a young age that Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms et al…. are “great” composers. Revering the music in this way can create problems when learning and playing it: for pianists, as for other musicians, certain works – the Goldberg Variations and the Well-Tempered Clavier, Beethoven’s 32 Piano Sonatas, Chopin’s Études, the great piano concertos, for example – have an elevated status on a par with the works of Aristotle, Shakespeare or Dickens. We hold the music in awe and feel a tremendous responsibility towards it. Thus, the musician is like a conservator or gardener, bringing these great works to life.

Statue of Glenn Gould

I had to stop myself listening to other people play it or there would no hope in hell of me finding my own way with it.

– Jonathan Powell, pianist

There are however ways to mitigate this. Listening to great recordings and performances does no harm. They can inspire and inform, highlighting aspects of the score which may not be obvious from our initial study of it, sparking ideas, and nourishing our perceptions of the music. We can admire the great interpretations of the music we are studying, but should never seek to imitate nor borrow from someone else’s version. Acknowledging the greatness rather than revering it can be helpful too: after all, if we continually keep the music on unreachably high pedestals, we may never actually play it, thus denying ourselves the opportunity of experiencing something truly wonderful and the sense of being part of an ongoing process of recreation every time we play or perform the music.