My version of Bach’s C major Prelude will not be the same as yours. Sure, we’ve been working from the same score, processing the same notes, we may even play the piece on the same instrument, but it won’t be the same when you play it. Because when you play it is your piece, and when I play it, it is mine.

Taking ownership of one’s music, literally making it one’s “own piece”, is something that musicians strive for. A strong sense of ownership connects one to one’s music, and also creates a special communication with the audience.

Ownership is hard won, however, and comes from close study and deep knowledge of the score to fully acquaint oneself with the composer’s message and intentions. All the explicit information contained within the score must be processed, understood and acted upon – the notes, dynamic, rhythmic and articulation markings, tempo, expression and character directions, and all the technical aspects of the music; in addition, implicit directions need to be considered and factored in: a rising passage may suggest a slight crescendo or stringendo, rests and fermatas suggests breathing space, a doubling of octaves may indicate a more orchestral sound or texture. The ability to process and interpret implicit directions comes from the musician’s own musical knowledge, training, an understanding of historical contexts and performance practice (in, for example, Baroque music), experience and maturity and personality, but even the most junior student can gain some of this ‘special knowledge’ by exploring other repertoire by the same composer and his/her contemporaries, either by playing or listening to it.

Ownership is hard won, however, and comes from close study and deep knowledge of the score to fully acquaint oneself with the composer’s message and intentions. All the explicit information contained within the score must be processed, understood and acted upon – the notes, dynamic, rhythmic and articulation markings, tempo, expression and character directions, and all the technical aspects of the music; in addition, implicit directions need to be considered and factored in: a rising passage may suggest a slight crescendo or stringendo, rests and fermatas suggests breathing space, a doubling of octaves may indicate a more orchestral sound or texture. The ability to process and interpret implicit directions comes from the musician’s own musical knowledge, training, an understanding of historical contexts and performance practice (in, for example, Baroque music), experience and maturity and personality, but even the most junior student can gain some of this ‘special knowledge’ by exploring other repertoire by the same composer and his/her contemporaries, either by playing or listening to it.

Beethoven: Cello Sonata No. 3 in A Major, Op. 69 – II. Scherzo: Allegro molto

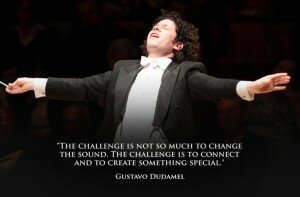

Such disciplined learning and study gives one the confidence to play the music convincingly and to create one’s own personal vision of the music. I have been to concerts where it is evident that the music is well learnt, all the details taken care of, but it doesn’t communicate, or touch one’s emotions. A non-committal performer may tread the middle road, providing a pleasing range of dynamics, expression and so on, but without a real sense of conviction which robs the performance of that special edge of excitement. Audiences can certainly feel this and may leave the concert satisfied but unmoved.

So, ownership is about having done the detailed work on the score to give one the confidence to perform the music convincingly. But there’s more: ownership also creates spontaneity, freedom, originality and sprezzatura in performance – the sense, to the audience, that everything one does is effortless. As a performer, one does not want to show the audience what one cannot do; instead, the performer reveals, through their ownership of the music, not only mastery, but also freedom, ease and delight, playing ‘in the moment’… Performers who have these qualities, and who have complete ownership of their music, are prepared to take risks in performance, secure in the knowledge that one never plays the same piece of music the same way twice. Such performances are thrilling and memorable.

More Opinion

-

The Predictability of the 2025 Van Cliburn Competition Was Hong Kong's Aristo Sham the 'predictable winner'?

The Predictability of the 2025 Van Cliburn Competition Was Hong Kong's Aristo Sham the 'predictable winner'? -

The Unpredictability of the 2025 Queen Elizabeth Competition Discover why these results have sparked debate among classical music fans

The Unpredictability of the 2025 Queen Elizabeth Competition Discover why these results have sparked debate among classical music fans -

What Makes a Good Concert? A memorable concert requires four essential elements. Find out here

What Makes a Good Concert? A memorable concert requires four essential elements. Find out here -

The Musician’s ‘Non-Negotiables’ Want to level up your music practice? Take inspiration from 'The Bear'

The Musician’s ‘Non-Negotiables’ Want to level up your music practice? Take inspiration from 'The Bear'