“Gaspard has been a devil in coming, but that is only logical since it was he who is the author of the poems.”

– Maurice Ravel

Considered to be one of the most fearsomely difficult pieces in the pianist’s repertoire (Ravel deliberately wanted to make the final movement, Scarbo, more difficult than Balakirev’s Islamey), Gaspard de la Nuit is a staple of the recital repertoire and one of Ravel’s most well-known works.

Composed in 1908, the inspiration for Gaspard comes from three poems by Aloysius Bertrand, and the triptych of pieces represents darkness, hallucinations and terrors through the medium of daring, advanced technical devices within a classical three-movement structure. Betrand’s poems appealed to Ravel’s love of fairytales and the fantastic, and the macabre stories of Edgar Allan Poe.

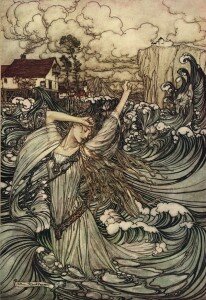

Ondine by Arthur Rackham

Gaspard is a triathlon for the pianist – a medium fast opening movement (Ondine), a slow middle movement (Le Gibet) and a fast, impressive finale (Scarbo) – and what is remarkable is that Ravel, although a mediocre pianist himself according to his contemporaries, was a master of the instrument, employing scales and arpeggios, polyrhythms, vague key signatures and harmonies, and articulations specific to the piano combined with his obsessive attention to detail, “to say with notes what a poet expresses with words.” (Ravel). He had composed music inspired by poems before, and was expert in creating vividly descriptive musical narratives (Jeux d’Eau, Albordao del gracioso). Gaspard represents the pinnacle of this talent, capturing minute details from Bertrand’s poems in highly evocative, almost painterly music.

“Part of the great difficulty of the piece is that none of its complications are gratuitous – every note is part of a precise effect, and the textures are generally very transparent. In other words, there’s nowhere to hide.”

– Steven Osborne, concert pianist

Ondine

“Listen! — Listen! — It’s me, it’s Undine who brushes these drops of water on the resonant panes of your window, illuminated by the mournful rays of the moon; and look, in a robe of watered silk, the lady of the chateau who contemplates, from her balcony, the beautiful starry night and the beautiful sleeping lake.”

from Ondine by Aloysius Bertrand

The liquid, sensuous shimmers of Ondine are a feat of coordination for the pianist’s fingers and brain. The music emerges out of nothing, starting ppp and through rapid contrary motion arpeggios, with each hand on different tonal keys to create dissonance, Ravel captures the swirling flow of water, and glittering splashes. It’s dreamy, fantastical and utterly seductive in its retelling of the fate of Gaspard who is charmed by the water-princess Undine, but cannot follow her into the watery depths because he is already married.

Maurice Ravel

Le Gibet

“It is the bell that tolls from the walls of a city, under the horizon, and the corpse of the hanged one that is reddened by the setting sun.”

from Le Gibet

From the swirling ocean to the desolate image of a corpse, suspended from a gibet, slowly swinging in the light of the setting sun. A mournful dead bell tolls in the distance. Ravel portrays the scene with a chilling simplicity and the entire focus of the piece is the creation of this eerie atmosphere, sustained by a B-flat ostinato that sounds throughout the entire piece. Around this sparse texture Ravel weaves haunting, strikingly piquant harmonies. On first sight of the score, the music looks fairly straightforward (especially compared to the outer movements), but its difficulty lies in independence of the hands and controlling discreet dynamic gradations of pp and ppp.

Scarbo

“How often have I seen him alight on the floor, pirouette on a foot and roll through the room like the spindle fallen from the wand of a sorceress!”

from Scarbo

Arguably the most famous movement of Gaspard, Scarbo depicts the fear of an evil dwarf who appears in the dead of night and plays with the narrator’s mind. It is by far the most difficult movement of the three with its transcendental virtuosity (myriad repeating notes) and was ahead of its time in its use of jagged, sometimes violent dissonance and highly advanced piano techniques. Like the original poem’s surreal narrative, the music is almost psychotically frenetic and bizarre, jumping from theme to theme, relentless and intense.

The entire work is an impressive window on Ravel’s inexhaustible and lively imagination and musical inventiveness. He never orchestrated it, perhaps believing it was intrinsically pianistic and should not be transcribed. It was, however, orchestrated by Eugene Goossens in 1942, but the solo piano version remains one of the most significant and celebrated additions to the concert repertoire, at the apex of virtuosity.

The only way to achieve happiness is to cherish what you have and forget what you don’t have

Thank you!

Well-written article, but Ondine is “slow,” not “medium fast.”