Sir Walter Scott

The Scottish author Sir Walter Scott is second only to Shakespeare for the number of musical pieces that his works, both plays and poetry, have inspired. Some of the operas he inspired are still standard on the opera stage today while others have faded from our hearing.

Scotland, hovering on the edge of Europe, fed its Romantic imagination first with poetry then with novels, many based on historical incidents. Scott’s novels, with its heroic but realistic characters, set in the remote past, were ideal for operatic setting. Scott was well-aware of the limits of the operatic treatment knowing that his dialogues, the historical details, the geographical setting, and the narrative flow could not all fit comfortably on a stage. After seeing a French production of Ivanhoé, which used the music of Rossini with new words, all Scott could say was that ‘It was superbly got up … It was an opera, and of course the story greatly mangled, and the dialogue in a great part nonsense’.

Robert Taylor as Ivanhoe (1952)

Nonetheless, librettists and composers found Scott a source of much inspiration. The two principal works that received operatic treatment were Ivanhoe (1819) and Kenilworth (1821). His novel The Bride of Lammermoor (1819), although more famous to us now as Lucia di Lammermoor, had fewer settings.

Ivanhoe, set in 12th-century England, is credited for the revival of interest in medievalism in the early 19th century. Its tale of knights returning from the Holy Land, tournaments with disguised combatants, religious conflict, and the heroic return of King Richard inspired both writers and composers. Characters who later became recognized as “medieval England standard,” including Robin of Locksley (Robin Hood) and the evil Prince John ruling in the stead of his brother King Richard all have important roles. Ivanhoe, in a break with long-standing norms of heroic literature, is not a superman but a regular man. He’s in the center of the action but is wounded, has to be rescued by King Richard, has to have the King intercede with him with his father, and so on.

Lysette Anthony as Rowena (1982)

Ivanhoe operas were created by John Parry, Giovanni Pacini (1832), Attillio Ciardi (1888), and Sir Arthur Sullivan (1891). Ivanhoe opera with different names include Maid Marian by Henry Bishop (1822), Ilda d’Avenel by Francesco Morlacchi (1824) and Giuseppe Nicolini (1828), Der Templer und die Jüdin by Heinrich Marschner (1829), Il templario, by Otto Nicolai, (1840), Adelaide di Borgogna al castello di Canossa by Alessandro Gandini (1841), Ivanoé by T. Sari (1863), Rebecca by B. Pisani (1865), and Rébecca by A. Castegnier (c1882).

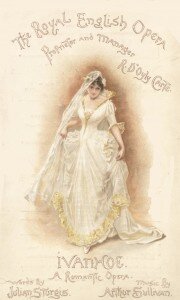

The Programme for Sullivan’s Ivanhoe (1891)

Sir Arthur Sullivan’s grand opera, Ivanhoe, opened on 31 January 1891 and ran for an unprecedented 155 performances, but, after that initial hit, the opera quickly faded into history. Richard D’Oyly Carte had built the new Royal English Opera house specifically for Ivanhoe, but couldn’t fill the house and eventually sold it.

Sullivan: Ivanhoe: Act I, scene I: Introduction (BBC National Orchestra of Wales; David Lloyd-Jones, cond.)

Sullivan: Ivanhoe: Act III Scene 3: See where the banner of England floats afar … (Janice Watson, Rowena; Geraldine McGreevy, Rebecca; Neal Davies, King Richard; Toby Spence, Ivanhoe; Peter Rose, Cedric; Adrian Partington Singers; BBC National Orchestra of Wales; David Lloyd-Jones, cond.)

Allom: Queen Elizabeth’s Arrival at Kenilworth (1837)

For a heroic film setting, we have 1952’s Ivanhoe, with Elizabeth Taylor as Rowena and Robert Taylor as Ivanhoe, with music by Miklos Rózsa, which was nominated for an Academy Award.

Rózsa: Ivanhoe: Overture (National Philharmonic Orchestra; Charles Gerhardt, cond.)

Kenilworth, set in the time of Queen Elizabeth I, gives us some of the solidly Romantic themes of a hidden marriage, a false declaration of bachelorhood, false declarations of marriage, denying a confession was true because the confessor was mad, and the fortuitous death of a wife when a queen was available for marriage. It’s a full program!

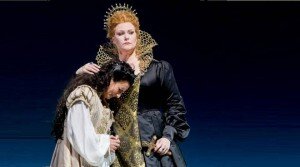

Donizetti: Elisabetta al castello di Kenilworth: Bergamo 2018

Kenilworth was set under that title by V. Schira (1848), George Macfarren (1880), B.O. Klein (1895), and H. Löhr (1905–6). It was also set as Leicester by Auber (1823), Elisabetta al castello di Kenilworth by Donizetti (1829), Elisabetta by P. Sogner, (1830); in Polish as Zamek Kenilworth by J. Damse, (1832); in Danish as Festen paa Kenilworth by Christoph Weyse to a libretto by Hans Christian Andersen (1836). In German, it was set as Emmy by Carl Loewe, (1842) and Das Fest zu Kenilworth by Eugen Seidelmann (1843), and Italian as Amy Rosart by G. Caiani, and as Il conte di Leicester by Luigi Badia (1851) and by A. Baur (1858). It was also set as a masque by Sir Arthur Sullivan for Birmingham (1864).

In the ending of Donizetti’s opera, the story is changed: Queen Elizabeth intervenes, forgives Leicester for toying with her affections, and returns him to his wife.

Scott’s attraction as an operatic source continued through the 20th century, with one of the most recent settings including Guy Mannering (1815) by Lionel Lackey in 1980.