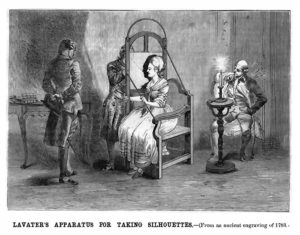

Lavater taking a silhouette

In his ground-breaking book on physiognomy, the Swiss writer Johan Kaspar Lavater (1741-1801) sought to find the face of God in the men around him. Taking literally the notion that God created man in his own image, Lavater, sought to document the good and the bad in nature, all through reading a person’s face. Lavater sought images from his subjects and also made silhouettes of them.

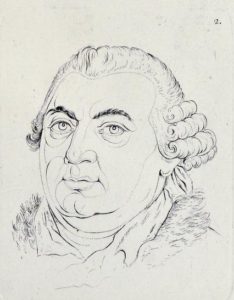

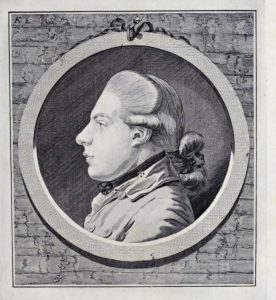

Niccolò Jommelli

Lavater was another of the 18th-century scholars who sought to systematize and catalogue the world. The advent of the microscope made examination of the very small worlds that were around us available to be studied. Similarly, the availability of pictures made Lavater’s study of the face much easier. Lavater’s work appealed to a population that was eager to feed its desire for sentimentalism and emotional intimacy.

In the third volume of his 4-volume examination of the face of man (Physiognomische Fragmente zur Beförderung der Menschenkenntnis und Menschenliebe, 1778-78), he started looking at professions, such as artists and musicians, and the faces of its followers.

Niccolò Jommelli

When Lavater got to musicians, he looked at three ‘musical geniuses’: Niccolò Jommelli (1714-1774), C.P.E. Bach (1718-1788), and Philipp Christoph Kayser (1755-1823). Jommelli and Bach were contemporaries who were the most influential composers of their time; the younger Kayser was a follower of C.P.E. Bach and close friend of Goethe.

Jommelli, working in Naples, Rome and other major cities of Italy, put some 80 operas on the stage between 1737 and 1774. Most of these were opera serie, or operas of a dramatic turn (versus opera buffa, comic operas). He made a number of innovations in Italian opera, including the addition of dances (in the French style), adding the orchestra to the recitatives (in the German style), and using the orchestra more dramatically to underline the onstage drama.

Niccolò Jommelli

Lavater read Jommelli’s face as that of a musical genius. It’s clear from Lavater’s writing that the portrait presented is not only an image of the man but also a representation of what Lavater already knows of the subject’s character, including the character that Laveter reads/hears in his music. Lavater writes of Jommelli: “The face, with its courageous eyes, powerful nose, and abundant chin, speaks of genius and indicates that one can expect ‘more fire than precision in his works; more pomp than elegance; more ravishing force than soft pleasing tenderness…”

Niccolò Jommelli

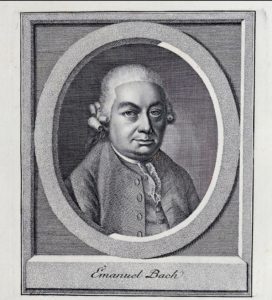

C.P.E. Bach was the fifth child and second son of J.S. Bach. His style spanned the end of the Baroque era so well represented in his father’s music, and the new coming classical style. His own style tended towards increased expression and became a representative of empfindsamer Stil (sensitive style). He used the new principles of rhetoric and drama to create a sound that was much more dynamic than what had come before.

CPE Bach

C.P.E., known as the ‘Berlin Bach,’ and later the ‘Hamburg Bach,’ in contrast with his younger brother J.C. Bach, ‘the London Bach,’ is captured by Lavater in his more common name, Emanuel Bach. For Lavater, C.P.E. Bach was the most famous of the Bach family. In his first letter to Emanuel, he described himself as “your admirer and worshiper”.

Lavater’s reading found in Bach “the face of original genius, the creator of a new taste, the maker of an entire epoch.” Between his eyes, Lavater saw “the spirited expression of great creative powers.” The mouth showed “refined feeling and self-confidence.” The face as a whole tell Lavater that this man will produce great things. Lavater exclaims: He is a creator! He is original! All his products are stamped with originality…!

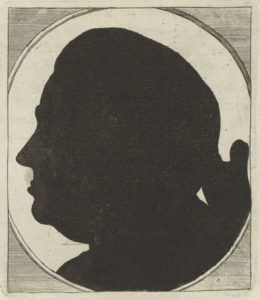

CPE Bach Silhouette

Bach’s reaction to his reading by Lavater was duo-fold: on one hand, he thought the engraving that was produced from the picture he’d supplied made him look “half asleep” but on the other, he thought that Lavater’s reading was “confident and conclusive.”

C.P. Kayser’s music isn’t well known today. He’s best known for setting texts of his friend Goethe. Lavater, on the other hand, saw between his nose and over-lip, indications of a deep intimate sensitivity and a poetic spirit. As a music genius, he hasn’t stood the test of time, but Lavater only knew him as youth of 22.

Laveter: Kayser

The reading of personality and genius through the face came to an end as late as the 1940s. Attempts to understand the inner person through study of outward appearance became too shallow to capture the true complexity of people. It is interesting, however, to see Lavater’s comments on the composers he knew and admired. It gives us a sense of how they were seen by their contemporaries.